Category: Liberalism

September 20th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

I was born in 1946. I lived in a council house until I was 16. My family were Labour. My privilege was not money, but that my parents and grandparents all valued education and culture. But none of them obtained a university degree, because they were less accessible at the time.

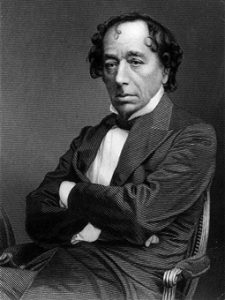

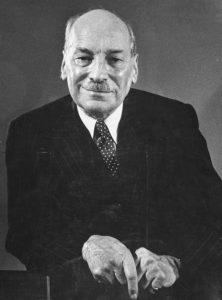

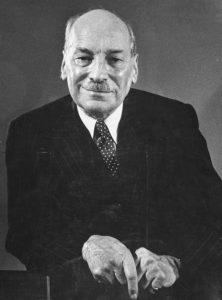

Harold Wilson

I became involved in the Labour Party in 1964 and then saw myself as a Tribune socialist following the steps of great radicals such as Michael Foot. After welcoming Harold Wilson’s election victory in 1964, I became critical of the new Prime Minister because of his nominal support for the US in the Vietnam War.

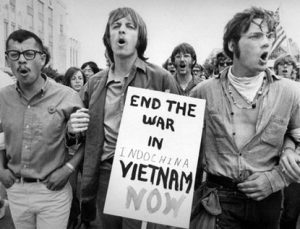

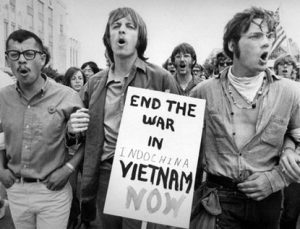

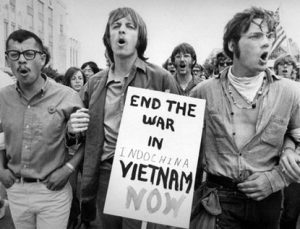

Vietnam and Marxism

For my baby-boom generation, the Vietnam War was a great generator of radicalism. Like many of my university friends, I became a Marxist in 1966. We were drawn into a turbulent and exciting world that combined activism with ideas and debate. I saw myself as a Marxist until about 1980.

I studied mathematics and philosophy from 1965 to 1968 and economics from 1972 to 1974. Both periods were at the University of Manchester. In the intervening years I taught myself Marxist economics. My knowledge of economics became enduringly significant in my political evolution.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

Marxists dominated the activists on the university campuses. The left was divided and fractious. There were Soviet Bloc loyalists in the Communist Party of Great Britain. There were lovers of Mao Zedong and several rival Trotskyist sects. I could not bring myself to support any totalitarian regime – East or West – so I joined the forerunner of what is now the Socialist Workers’ Party, which saw everything existing as “capitalist”.

My departure from the SWP came in 1971 when they expelled a dissident faction with which I sympathised. (That critical faction eventually became the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, of Momentum fame in the Corbyn Era.)

I flirted briefly with the International Marxist Group, which included glamorous figures such as Tariq Ali, and Robin Blackburn of the New Left Review. The IMG was stronger in its support for the women’s movement and for gay rights.

After a few years among the sects I could see that something was wrong. These groups were aiming to help create a much better society, but they were generally dogmatic and intolerant. Some were ruthless, pugnacious and fanatical. I did not want to see any social system facilitated or run by these people.

But on the other hand I then accepted the Marxist view that capitalism was exploitative and frequently led to oppression and war. The evidence of this was seemingly before our eyes.

Re-joining Labour and changing strategy

After Labour’s electoral defeat in 1970, there was a strong and growing left in the Labour Party and that seemed the best hope for socialists. Against the advice of Ralph Miliband (whom I knew personally) and others, I re-joined Labour in 1974.

In 1975 I published a pamphlet entitled Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism. This tried to explain the fanaticism and intolerance of many Marxists in terms of their belief in the imminent decay and collapse of capitalist democracies. Trotskyists had failed to appreciate the enormous expansion and dynamism of capitalism after 1945. Their explanations of the survival of capitalism were weak.

Published in 1977, a longer work entitled Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy elaborated more of my thinking. Marxist-Leninists believed that parliament and the capitalist state should be “smashed”. Influenced by Max Weber and others, I argued that in modern democracies, government drew their perceived legitimacy from parliamentary elections. If socialism became a majority view, then socialists could and should gain a majority in parliament.

In the book I criticised the 1968 revolutionary movement in France for boycotting the elections called by President Charles de Gaulle in that year. Victory in the elections gave de Gaulle legitimacy. The huge movement of students and workers was crushed.

Paris – May 1968

As I had anticipated, my heresies were dismissed out of hand by the far left sects. But the book proved to be rather influential in the UK and internationally. It received a strongly sympathetic hearing on the Labour left. It was translated into Italian, Japanese, Spanish and Turkish. It persuaded a leading member of the violent Basque separatist group ETA to abandon terrorism.

I don’t know if he read my book, but Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the leader of the revolutionary movement in France in May 1968, later argued that it had been a mistake to boycott the French parliamentary elections.

Labour had been reconciled to the parliamentary road to socialism since its formation. The sects argued that it wouldn’t work. My response was that insurrection would not work either. In democracies we needed a combination of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary action.

Questioning ends as well as means

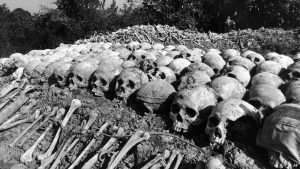

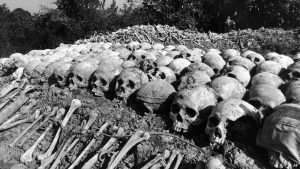

The killing fields in Cambodia affected me deeply. After seizing power in 1975 the Khmer Rouge forced everyone into the countryside and obliterated about two million people – a quarter of the Cambodian population – in the pursuit of their communist utopia.

I could not dismiss this as an aberration. After all, the Khmer Rouge aims, which included the abolition of money, private property and markets, were central to the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

Khmer Rouge Killing Fields

The far left were able to publish papers and debate ideas because they lived in a democracy that tolerated freedom of expression. But the ideas and actions of the sects, if they gained influence or power, would curtail these very liberties upon which they had depended.

Crucially, I was not naïve enough to believe that freedom and political pluralism could be guaranteed simply by the goodwill of a more enlightened Marxist leadership, who valued these things more than the Khmer Rouge. Good intentions were not enough.

I had retained a good lesson from Marxism. Effective ideas and practices draw their strength from agglomerations of power sustained by the structures of the politico-economic system. Hence a genuinely pluralist and tolerant political sphere depended on pluralism and decentralisation in the economic domain. A pluralist polity requires a pluralist economy.

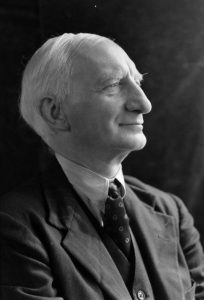

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Prominent Labour thinkers such as Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and G. D. H. Cole had all argued for a decentralised socialist system. But they still sought the abolition of private property and markets. The state would ultimately own everything. So what institutional, legal or other politico-economic forces could stop it retrieving all delegated powers to the centre, when deemed required, or when goodwill wore thin?

Any viable socialism always needs markets

I came to the view that genuine and lasting decentralisation would depend on the existence of organisations with some genuine autonomy and legal independence, providing powers to own property and trade with other organisations. Any viable socialism would always need markets – it was not simply a matter of tolerating or compromising with them.

This crucial transition of my thinking occurred between 1977 and 1980. I cannot recall the detailed influences. But I am sure that the initial impetus did not come from Ludwig von Mises or Friedrich Hayek. I did not delve deeply into their works until the early 1980s.

János Kornai

There had been several socialist proposals to nationalise the sector producing capital goods but retain competition and markets for consumer goods. I was more attracted by the Hungarian economist János Kornai’s more sophisticated proposal (originally published in 1965) to use a dynamic combination of markets and planning, where planning provided strategic impetus, and markets signalled information and gave scope for innovation and planning adjustment.

Over the new year of 1979-1980 I went on a short tourist group visit to the Soviet Union. Some of my companions were dewy-eyed admirers of the system, but I was prepared for its flaws, including the ubiquitous black markets and corruption.

I had been given the address in Moscow of an Englishman married to a Russian. As a former Communist, he explained in detail in his apartment how and why his views had quickly changed: “I challenge any supporter of the Soviet Union to live here just for six months.”

Alec Nove

When Alec Nove published a classic article on feasible socialism in New Left Review in early 1980 I was ready for it. Nove also argued that markets were essential to any viable socialism. He realised that he was attacking deeply-ingrained orthodoxy on the left.

(Later I had the pleasure of meeting both Kornai and Nove several times. Nove died in 1994 but Kornai is still alive. I am delighted to be invited as a keynote speaker at a conference in his honour in Budapest in 2018.)

Labouring as a revisionist

Any acceptance of markets was an anathema to followers of both Karl Marx and Tony Benn. Benn distanced himself from those who supported the persistence of markets.

But I found common ground with Benn and others over what was called “the alternative economic strategy”. I outlined my positive views on this in a pamphlet entitled Socialist Economic Strategy in 1979. It was published by Independent Labour Publications.

Independent Labour Publications was the residue of the old Independent Labour Party, which had played a central role in Labour history from the 1890s to the 1940s. The Independent Labour Party split from the Labour Party in 1931. But in 1975 it formally dissolved as a party and rejoined Labour as Independent Labour Publications.

I was involved in this organisation briefly. Despite outward appearances they turned out to be another sect, lacking any vision of a workable socialism. They too were uneasy about my revisionism. Although my Socialist Economic Strategy was a bestseller by their standards, they refused to reprint it. We parted company in 1981.

Geoff Hodgson, Jean Shepherd & John Maguire in 1979

In 1979 I was the unsuccessful Labour Parliamentary Candidate for Manchester Withington. The seat became Labour in 1987.

I met Benn a few times and supported him in the 1981 deputy leadership election. This alignment was marked in my book Labour at the Crossroads, published in that year. Therein I again supported the alternative economic strategy. But against Benn himself, I argued in that book that in some sectors of the economy “there is no substitute for competition and a market” (p. 206).

(In his important book on The Labour Party’s Political Thought, Geoffrey Foote quotes me (pp. 320, 347) as a “Bennite”. But because of my explicit acceptance of markets, I was unrepresentative of the Bennite stream of thought.)

Subsequently my opinion of Benn shifted. He was a magnificent speaker, but his writings on socialism are vague and unclear. His use of history is unscholarly and cavalier. He was not a well-read intellectual like Michael Foot.

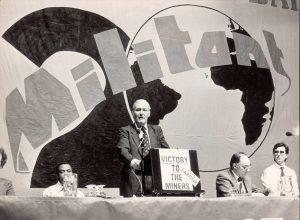

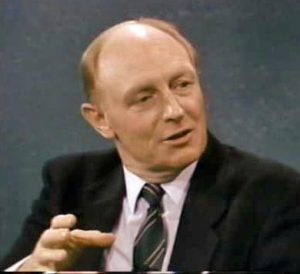

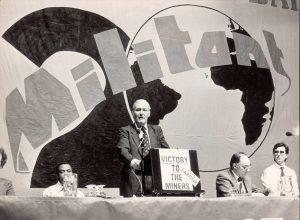

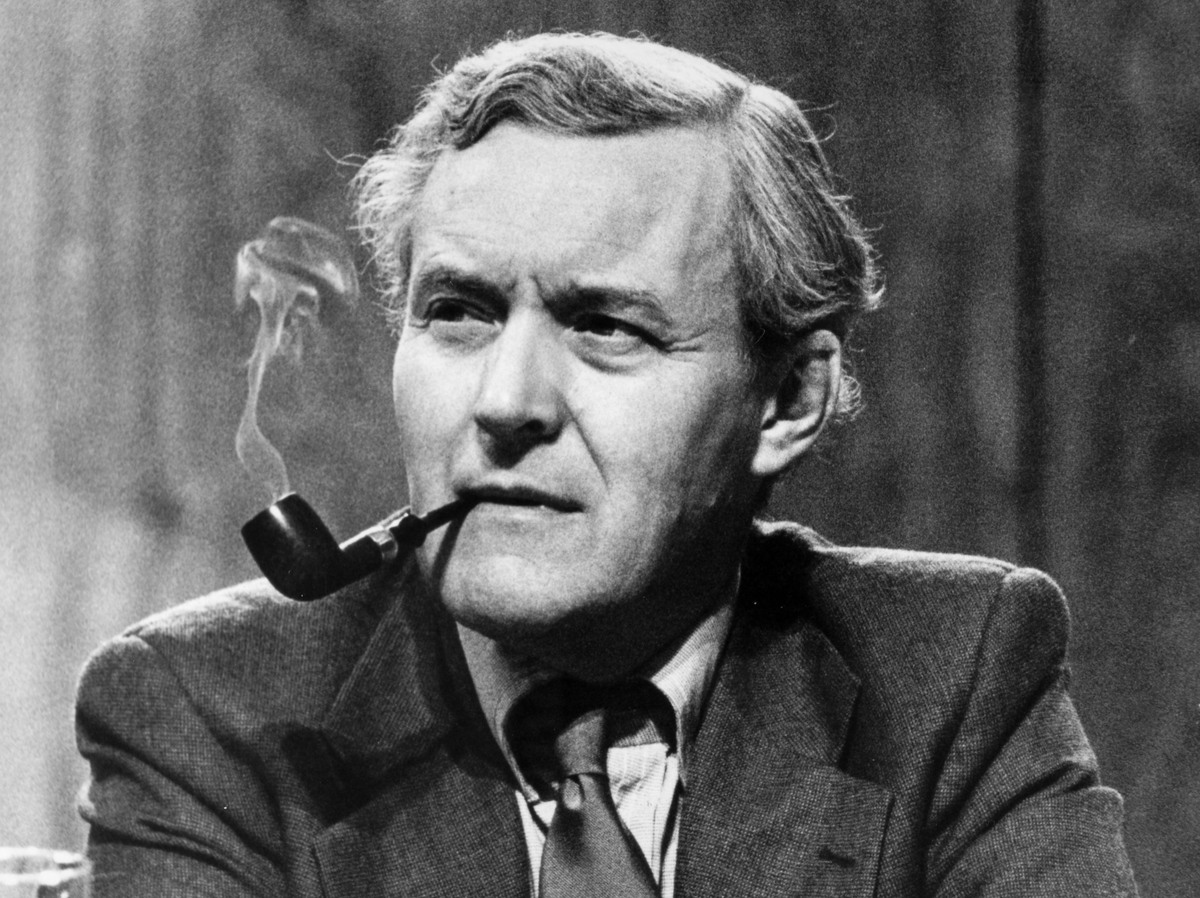

Tony Benn at a Militant meeting

While Benn’s “alternative economic strategy” accepted markets and a private sector for the present, it seemed to me that he wanted to move eventually toward a socialist economy without any markets at all. It was no accident that Benn and his followers defended the Trotskyist sect Militant when they were pushed out of the party from 1985 to 1992.

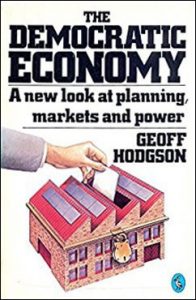

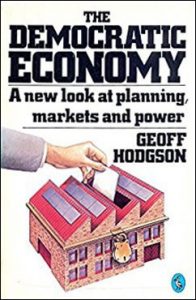

In 1984 I published my book on The Democratic Economy, where I set out my view on the importance and complementarity of both markets and planning. My argument was framed in socialist language but therein I distanced myself from Marxism. The book received a critical response from many on both the soft and hard left.

The Labour Coordinating Committee

Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. One of Thatcher’s most popular policies was to promote the sale of council-owned housing to the tenants. Labour had opposed this policy. The disastrous 1983 defeat of Labour on a Bennite manifesto prompted a rethink, on this and several other issues.

For some of us, this rethink amounted to more than expedient doctrinal trimming. Encouraging home ownership was really a good idea: why should all property be owned by the rich? But while supporting home ownership, we argued that the government should also build more social housing and enlarge the stock available for rent by low-income families.

But these ideas met stiff resistance in the Labour Party ranks, and not simply from Trotskyist entryists such as Militant. The resistance from Benn and his supporters was substantial and even more enduring. It was clear that old-fashioned socialist ideas still had a tenacious appeal among Labour’s membership.

The Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) became one of the primary modernising forces within Labour. Its leadership included Hilary Benn, Cherie Blair, Mike Gapes, Peter Hain, Harriet Harman, Kate Hoey (the Brexiteer) and others of enduring fame. I was elected to the LCC executive committee. We worked closely with the new leader Neil Kinnock, and with members of his shadow cabinet, including Robin Cook.

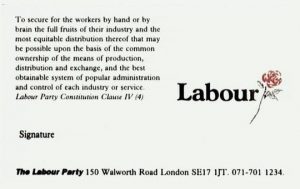

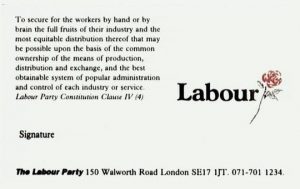

Changing Clause Four

I have detailed elsewhere my LCC attempt to bring about discussion to change Labour’s Clause Four. The version that had been in place since 1918 called for the “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”. This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector.

Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

Against my efforts, the 1983 AGM of the Labour Coordinating Committee defeated the proposal that Clause Four should be rewritten. This was out of fear of antagonising the Benn wing. Instead, the LCC resolved that Clause Four should be “clarified”.

But a resolution on long-term aims, which I had helped to draft, was passed by a large majority. The resolution called for the Labour Party to draft a new statement of aims, upholding “that socialism involves extended democracy and real equality. Democracy under socialism is extended to industry and the community … and must involve a substantial decentralisation of power.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

But there was strong hostility to these mildly revisionist ideas from within Labour’s ranks at the time, including from Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Benn.

Tony Benn & Jeremy Corbyn

The Guardian newspaper reported the LCC conference with the headline: “Labour breaks taboo on ownership”. For a while, the LCC tried to keep the conversation going on the need to revise Labour’s aims. The LCC held a conference in Liverpool in June 1984 on “The Socialist Vision”. But enthusiasm for this discussion fizzled out. By 1985 the LCC’s revisionist initiative had been kicked into the long grass. My efforts had failed.

But to their credit, Neil Kinnock and his deputy Roy Hattersley saw the need for Labour to modernise its aims. I advised them both for a while. But after 1987 I became less active in the Labour Party. My inactivity was born partly out of frustration that it was so difficult to shift Labour from its congenital hostility to markets and private enterprise.

But after a fourth election defeat in 1992 the party became more pliable. Tony Blair was elected as leader in 1994. Blair successfully changed the wording of Clause Four to endorse a strong private sector, but the dramatic rise of Corbyn in the party since 2015 shows that the old collectivist DNA has endured.

Towards liberalism

In many ways I have always been a liberal, especially in my support for freedom of expression, other human rights and democracy. By the late 1970s I also accepted the importance of markets and private property. But the emphasis in my thinking has shifted further in the last 30 years.

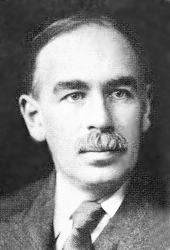

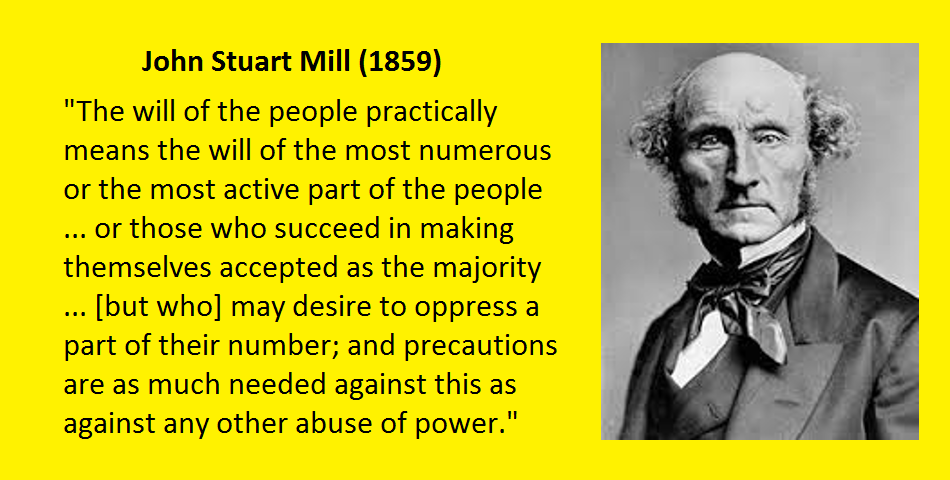

My academic works show a few markers of my political evolution. On page xvi of my 1999 book Economics and Utopia I wrote of my common ground with the US liberal John Dewey and with

“British social liberalism, which stretches from John Stuart Mill through Thomas H. Green to John A. Hobson, John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge.”

These thinkers still inspire me. But I would now also stress the importance of Thomas Paine. Other heroes include George Orwell and Arthur Koestler.

So by 1999 I was a true liberal, of social-democratic stripe. I had already moved some distance from the ideas in my 1984 book, which had over-stressed the possibilities for large-scale planning and for extensive democratic decision-making in large, complex economies.

But I still believe in judicious state intervention and regulation, and I am still an enthusiast for experiments with worker cooperatives and other forms of worker and community participation. With their lower levels of economic inequality, I see the Nordic countries as good role models for in the rest of the capitalist world.

From leaving Labour to joining the Liberal Democrats

In 2001 I left the Labour Party because of Blair’s energetic support for faith schools, Labour’s inadequate proposal for House of Lords reform and its neglect of the problem of economic inequality. I would have left over the Iraq War. Previously I had sometimes voted tactically for the Liberal Party, when they were second behind the Tories in my constituency. But what was tactical was also in growing part a matter of conviction.

I voted Liberal Democrat in the 1997, 2001, 2005 and 2010 general elections. But I did not approve of the coalition with the Tories. So the Liberal Democrats did not get my vote in 2015.

I re-entered political activity in 2016 after the Brexit referendum. My wife (Vinny Logan) had been a critical but close companion on my long journey since 1980. But unlike me she had always voted Labour. After the Brexit vote she joined the Liberal Democrats and I followed her after a few days. It will be a long hard slog to change British politics for the better, but it is vital that we try.

My wife and I were each brought up in a social culture where the Tories and the Establishment were the enemy, and the Liberals were seen as wishy-washy waverers in the class war. Labour was the only game in town.

It takes a long time to remove these ingrained preconceptions and learn that liberalism is the greatest legacy of the Enlightenment. It is the strongest guardian of both prosperity and freedom. Although Liberals have been in a minority, they are largely responsible for the foundation of the British welfare state. The NHS was originally a Liberal proposal. The Liberal Democrats constitute the most pro-EU party in the UK.

But some Liberal Democrats do not understand that it is the job of government in a recession to increase effective demand, particularly by increasing investment and raising disposable incomes for the poor. But the party is a broad church, and I will argue my corner in favour of Keynesian liberal economic policies.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

Today, both the Conservatives (now ruled by deceitful nationalists) and Labour (where the rising hard left dominate the timid moderates) are dangerous threats to the liberal and democratic rights and values that in the past we have taken too much for granted. We must now stand up to defend those rights and values, against dogma, ignorance, intolerance, petty nationalism and deceit.

20 September 2017

Minor edits – 25 September 2017, 22 October 2017, 10 April 2018.

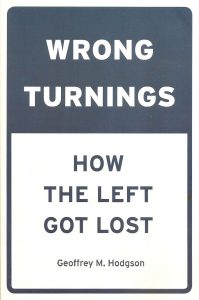

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Foote, Geoffrey (1997) The Labour Party’s Political Thought: A History, 3rd edn. (London: Palgrave).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1975) Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1977) Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1979) Socialist Economic Strategy (Leeds: Independent Labour Publications).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1981) Labour at the Crossroads: The Political and Economic Challenge to Labour Party in the 1980s (Oxford: Martin Robertson).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1984) The Democratic Economy: A New Look at Planning, Markets and Power (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1999) Economics and Utopia: Why the Learning Economy is not the End of History (London and New York: Routledge).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Kornai, János (1965) ‘Mathematical Programming as a Tool of Socialist Economic Planning’, reprinted in Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin), pp. 475-488.

Nove, Alec (1980) ‘The Soviet Economy: Problems and Prospects’, New Left Review, no. 119, January-February, pp. 3-19.

Nove, Alec (1983) The Economics of Feasible Socialism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Posted in Bertrand Russell, Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Khmer Rouge, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Ludwig von Mises, Mao Zedong, Markets, Nationalization, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Socialism, Soviet Union, Tony Benn

September 2nd, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

In terms of basic assumptions, Marxism has more in common with some prominent versions of so-called “neoliberalism” than is generally understood. Obviously, Marxism is opposed to a market economy. But some core ideas by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels are remarkably similar to those of some so-called “neoliberals”. For example, Marx’s definition of property resembles that of Ludwig von Mises.

But the parallels go much further, and are disturbing in their consequences. They concern the independence of the legal system and the nature and legitimation of democracy. They also concern the viability of civil society and the autonomy of personal and social life.

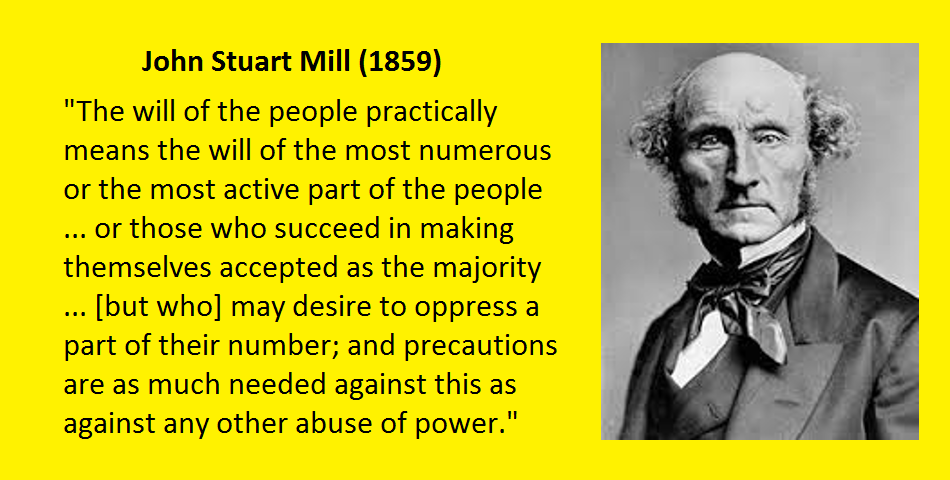

The argument here shows that liberalism – both historically and currently – is very different from some modern versions of “neoliberalism”. This “neoliberalism” is theoretically closer to Karl Marx than to Thomas Paine or John Stuart Mill.

Marxism undermines the autonomy of politics and civil society

The Marxian analysis of capitalism treats law and the state as an expression of class interests, which in turn are grounded on “economic relations”. Hence, for Marx, law and the state “originate in the material conditions of life“. They are part of the “superstructure” built upon the “economic base”.

The Marxist analytical reduction of everything to economics does not stop there. Consider the notion of civil society.

Civil society generally connotes a realm of free, partly self-organising, property-owning citizens, who interact under the rule of the state and its laws. In most accounts it includes private business and markets, but it is not reducible to them. It also embraces many forms of social association (including recreation, religion and philanthropy) that are not driven by business interests.

Thomas Paine

Distinctions between civil society and the state, and between civil society and the narrower world of trade and business, were developed by Enlightenment liberal writers such as Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, Thomas Paine, Alexis de Tocqueville and others. They are crucial for modern liberal theory.

In its analysis of capitalism, Marxism made the state, law, politics and civil society all analytically subservient to markets and business.

These may be regarded as extreme formulations within Marxism. Certainly there are more sophisticated treatments by Marxists of civil society and the state, not least by Antonio Gramsci. But Marxism is severely impaired by the words of its founders.

The above extracts concern the Marxian analysis of capitalism, not its vision of an ideal society, which of course is strikingly different from that of (neo)liberals. While the Marxian analysis of capitalism undermines the conceptual distinction between civil society and the state – by making them both subservient to economic relations – Marxian politics also dissolves it in practice.

In his early tract On the Jewish Question, Marx argued that civil society and political society should become one and the same. In practice, under socialism, once much of the economy becomes a state bureaucracy. With private association under restriction, the scope of civil society is much diminished.

The conceptual and practical degradation of civil society is but one of the roots of totalitarianism within Marxism. Other sources are discussed elsewhere. The smothering of civil society within the party-state makes opposition more difficult and paves the way to dictatorship – a process witnessed in all Marxist regimes, from Russia to Venezuela.

The conceptual and practical degradation of civil society is but one of the roots of totalitarianism within Marxism. Other sources are discussed elsewhere. The smothering of civil society within the party-state makes opposition more difficult and paves the way to dictatorship – a process witnessed in all Marxist regimes, from Russia to Venezuela.

The reclamation of civil society by Eastern European dissidents

Long before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, underground opposition groups had developed in several Soviet Bloc countries. After the crushing of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, and after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, opposition to the Marxist party-state became most developed in Poland.

Leszek Kolakowski

In 1971 the Polish intellectual Leszek Kołakowski wrote his Theses on Hope and Despair. These were circulated illegally in his home country.

Kołakowski complained that the Soviet-style regime had “monopolistic power” that impelled “the atomization of society and the destruction of all forms of social life not prescribed by the ruling apparat.” He called for a pluralist society with genuine freedom of information, discussion and association.

Subsequently, other Eastern European intellectuals such as Jacques Rupnik called for “the rebirth of civil society”. After the formation of the mass trade union movement Solidarity in Poland in 1980, still more voices were added. The Hungarian Andrew Arato wrote in 1981 of the new dissident wave:

Subsequently, other Eastern European intellectuals such as Jacques Rupnik called for “the rebirth of civil society”. After the formation of the mass trade union movement Solidarity in Poland in 1980, still more voices were added. The Hungarian Andrew Arato wrote in 1981 of the new dissident wave:

“one point unites them all: the viewpoint of civil society against the state – the desire to institutionalize and preserve the new level of social independence.”

Before its unexpected elevation to political power in 1989, Solidarity saw itself as essentially a movement for the “self-defence” of civil society against totalitarian power.

But while the dissidents drew on Enlightenment and liberal thought, their political philosophy was often underdeveloped. After 1989, many former dissidents became influenced by extreme forms of market libertarianism. But given the parallels – explored below – between this “neoliberalism” and Marxist thought, there was more continuity in their thinking than immediately meets the eye.

Market universalism

To understand the connection between “neoliberalism” and Marxism we need first to address a much broader phenomenon within social science.

There is a widespread tendency to use the language of trade and markets to describe phenomena that are neither traded nor markets. I gave some examples in my Conceptualizing Capitalism book. I here call it market universalism.

There is a widespread tendency to use the language of trade and markets to describe phenomena that are neither traded nor markets. I gave some examples in my Conceptualizing Capitalism book. I here call it market universalism.

Consider the notion of a “market for ideas”, which can be found in the writings of Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase. He did not refer to intellectual property but to conversation and freedom of expression.

Douglass North, another Nobel Laureate, wrote of “political markets”. He was not referring to vote-buying (in countries like India) or political bribery, but to the general process of multi-party competition in a democracy.

In a paper published in 1988, Bruce Benson and Eric Engen envisioned “the legislative process as a market for laws” where interest groups “pay” legislators for laws as “products”.

By minimal criteria, none of these is a market. Rules concerning contracts, enforcement and property rights are lacking.

For example, the ordinary communication or debating of ideas does not involve enforceable contracts. Generally, conversation is not an intentional transfer of property rights.

Similarly, if we vote for a politician or a party that does not typically amount to an enforceable agreement. Competition between politicians or parties for votes or power is not a contest for contracts under any established system of contractual rules.

Likewise, with the supposed “market for laws”, in reality there are rarely any enforceable contracts between interest groups and legislators.

There is a further problem. What would be the system of rules under which these supposed “contracts” between legislators and interest groups are formed and enforced? Hence a “market for laws” would require supra-legal institutions with their own (legal or other) rules. We would need markets for markets-for-laws, or markets for meta-rules.

This reveals a problem of an infinite regress, showing that not everything can be placed on a market. My Conceptualizing Capitalism book gives further reasons why markets cannot be universal. There will always be missing markets.

Market universalism and “neoliberalism”

Although market universalism may be dismissed as the harmless use of metaphor, it contains dangerous policy temptations.

Making everything a market denies the autonomy of law and politics: everything is subsumed within the market zone. All forms of association are regarded as market-like or contractual arrangements. Legal and political relations or rights are reduced to the “economic” facts of possession or control.

The temptation is to downgrade all non-commercial justifications for democracy, law or social life. Everything is forced into the conceptual straitjacket of property and contract, and evaluated in terms of profit and loss.

Previous liberal thinkers had defended rights to private property, other human rights, plus institutions such as democracy. By contrast, market universalism can highlight control over property first, on the grounds that it is the foundation of all other rights and liberties. Property moves from being a necessary but insufficient condition of liberty, to being necessary and sufficient for the same.

This transforms the Enlightenment argument that the government must be legitimated by representative democracy, rather than by tradition or divine rule. The “political market” makes democracy a market, and market-like criteria become the overriding source of legitimation for everything.

This transforms the Enlightenment argument that the government must be legitimated by representative democracy, rather than by tradition or divine rule. The “political market” makes democracy a market, and market-like criteria become the overriding source of legitimation for everything.

Furthermore, democracy may be seen as secondary or expedient, especially when property or markets are perceived as being under threat. By treating democracy as another market, a temptation is to regard markets and property as generally more important or supreme than democracy.

Consequentially, market universalism enables something very different from other forms of liberalism, and it involves a radically modified conceptual foundation. One may be tempted to call it neoliberalism.

This is the label suggested by Philip Mirowski, who addressed what he called the Mont Pèlerin “thought collective”. In a perceptive essay on this influential intellectual movement, which involved Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises and others, Mirowski identified several of its traits including the following:

“Skepticism about the lack of control of democracy is offset by the persistent need to provide a more reliable source of popular legitimacy for the neoliberal market state. Neoliberals seek to transcend the intolerable contradiction by treating politics as if it were a market and promoting an economic theory of democracy.”

Foundations of anti-democratic authoritarianism

We can now see what Marxists and market universalists have in common. They all look upon capitalism as system where everything is reducible to a market.

For Marxists, this means that civil society is nothing more than the sphere of business and individual greed. In addition, the political and legal spheres are simply reflections of these business interests.

A policy consequence – after the socialist revolution – is to destroy civil society and absorb it into politics and the state. This forms part of the Marxist foundation for totalitarianism.

Of course, for “neoliberals”, markets are always beneficial. But the problem is much more serious than their ever-familiar agoraphilia.

Through notions such as “political markets” and “markets for laws”, market universalist “neoliberals” reduce the state and its legal system to a grand marketplace. The state and law become additional markets alongside others. The policy temptation is the practical marketization of the state and the doctrinal denial of the autonomy of politics.

Through notions such as “political markets” and “markets for laws”, market universalist “neoliberals” reduce the state and its legal system to a grand marketplace. The state and law become additional markets alongside others. The policy temptation is the practical marketization of the state and the doctrinal denial of the autonomy of politics.

Once politics and all civil society are seen through the lenses of trade and markets, then the basic elements of property and contract become supreme. Instead of being a necessary but insufficient precondition of liberty, property becomes both necessary and sufficient.

This transforms the Enlightenment argument that the government must be legitimated by representative democracy, rather than by divine rule. The “political market” makes democracy a market, and this becomes the overriding source of legitimation.

Consequently, democracy becomes secondary or expedient, especially when property or markets are perceived as being under threat. By treating democracy as another market, a temptation is to regard markets and property as generally more important or supreme than democracy.

Leading “neoliberals” like von Mises and Hayek have been described as classical liberals. But their views are a departure in important respects from the Enlightenment liberalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and from other more recent currents of liberal thinking. In some important respect they are closer to Karl Marx than John Stuart Mill.

Margaret Thatcher and Augusto Pinochet

Their supreme emphasis on property rights explains why some “neoliberals” have dallied with dictators. For example, in a book originally published in 1927, von Mises praised fascism as “an emergency makeshift” that “has, for the moment, saved European civilization”. Hayek was notoriously silent about the human rights violations in Chile under the dictator Pinochet. These fascist or dictatorial regimes were seen by them as saviours of private property.

Conclusion: liberalism is not “neoliberalism”

Despite their opposed policy stances, Marxism and the type of market-universalist “neoliberalism” discussed here have similarities at their theoretical foundations. While Marxism reduces the analysis of civil society and politics to an economistic world dominated by self-seeking egoists, this “neoliberalism” does exactly the same.

Within this version of “neoliberalism”, everything is legitimated by free contract in unfettered markets in all spheres of human interaction, including within the state itself. Like Marxism, it reduces everything to economics.

This entails a radical break from other forms of liberalism, and from all other doctrines that recognise the relative autonomy of the political and legal spheres from the economy and from civil society.

2 September 2017

Minor edits – 8, 10 September 2017

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

References

Arato, Andrew and Cohen, Jean (1992) Civil Society and Democratic Theory (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Benson, Bruce L. and Engen, Eric M. (1988) ‘The Market for Laws: An Economic Analysis of Legislation’, Southern Economic Journal, 54(3), January, pp. 732-745.

Caldwell, Bruce J. and Montes, Leonidas (2015) ‘Friedrich Hayek and his Visits to Chile’, Review of Austrian Economics, 28(3), pp. 261-309.

Cohen, Jean (1982) Class and Civil Society: The Limits of Marxian Critical Theory (Oxford, Martin Robertson).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Keane, John (ed.) (1988) Civil Society and the State (London: Verso).

Keane, John (1995) Tom Paine: A Political Life (London: Bloomsbury).

Keane, John (1998) Civil Society: Old Images, New Visions (Cambridge: Polity).

Kumar, Krishan (1993) ‘Civil Society: An Inquiry into the Usefulness of an Historical Term’, British Journal of Sociology, 44(3), September, pp. 375-395.

Mirowski, Philip and Plehwe, Dieter (eds) (2015) The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, paperback edition (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press). (Quote from p. xvii.)

Mises, Ludwig von (1985) Liberalism in the Classic Tradition. Translated from the German edition of 1927 (Irvington, NY: Foundation for Economic Education).

Polan, Anthony J. (1984) Lenin and the End of Politics (London: Methuen).

Venugopal, Rajesh (2015) ‘Neoliberalism as a Concept’, Economy and Society, 44(2), pp. 165-87. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013356.

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Karl Marx, Left politics, Leszek Kolakowski, Liberalism, Ludwig von Mises, Markets, Neoliberalism, Politics, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Socialism, Soviet Union, Venezuela

May 21st, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Although the two biggest UK political parties are very different in important respects, Labour under Jeremy Corbyn and the Conservatives under Theresa May have each converged on different forms of pro-Brexit, economic nationalism.

Economic nationalism prioritises national and statist solutions to economic problems. Although it does not shun them completely, it places less stress on global markets, international cooperation and the international mobility of capital or labour. It believes that the solutions to major economic, political and social problems lie within the competence of the national state.

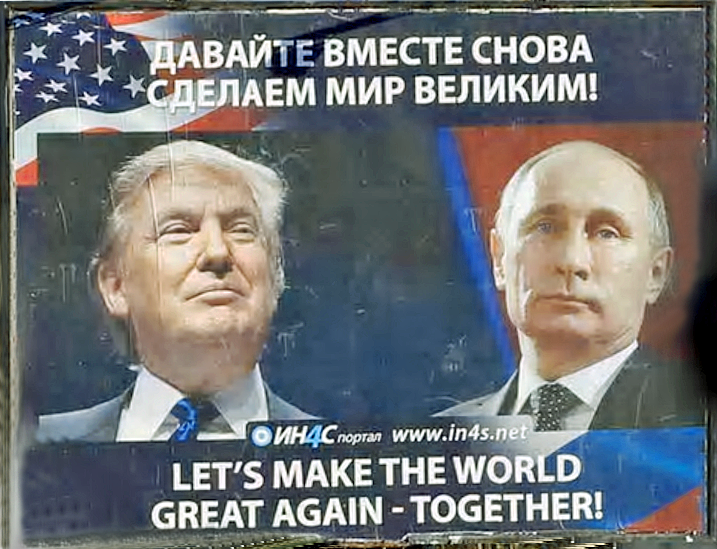

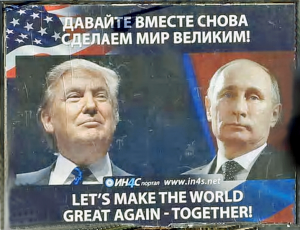

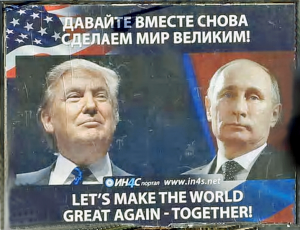

Other countries have turned in the same direction, including the United States under Donald Trump and Russia under Vladimir Putin. Previously, both Soviet-style and fascist economies have embraced economic nationalism. China has continued along this road, even after its acceptance of private enterprise and a market economy.

Other countries have turned in the same direction, including the United States under Donald Trump and Russia under Vladimir Putin. Previously, both Soviet-style and fascist economies have embraced economic nationalism. China has continued along this road, even after its acceptance of private enterprise and a market economy.

Economic nationalism has been used successfully as a tool of economic development, by creating a state apparatus to build an institutional infrastructure and mobilise resources. But it brings severe dangers as well as some advantages. Its reliance on nationalist rhetoric can feed intolerance, racism and extremism.

Furthermore, as it concentrates economic and political power in the hands of the state, economic nationalism undermines vital checks and balances in the politico-economic architecture.

As numerous social scientists (from Barrington Moore to Douglass North) have shown, democracy and human rights cannot be safeguarded without a separation of powers, backed by powerful countervailing politico-economic forces that keep the state in check.

From Thatcherism to Mayhem: Tory economic nationalism

Margaret Thatcher

In the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher changed the Tory party from a paternalist party of the elite to a more radical, free-market and individualist force, embracing the ideologies of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

A logical consequence of this market fundamentalism was to embrace the European Single Market, which her successor John Major did in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. But this was too much for the Tory nationalists, who were already turning against the European Union and all its works.

The tension grew within the Tories between those that pursued international markets in the name of market fundamentalism, and those who worried that global trade and the free movement of labour were undermining the powers of the British nation state.

A compromise option – widely touted during the June 2016 EU referendum – was to exit the EU but remain in the single market. But a major implication of this was that the free movement of labour to and from the EU would have to be retained. May became prime minister and declared that Britain would leave the single market as well as the EU.

This marks a major ideological shift within the Conservative Party. The pursuit of free markets, promoted so zealously by Thatcher, has moved down the Tory agenda, in favour of nationalism, increased state control, reduced parliamentary scrutiny, and lower immigration, whatever the economic costs.

Forward together: the new-old Toryism

This shift is signalled by a remarkable passage in the 2017 Conservative general election manifesto:

“We do not believe in untrammelled free markets. We reject the cult of selfish individualism.”

This could be interpreted as a cynical attempt to attract some Labour voters. Probably, in part, it is. But there is much more to it than that. It shows how all the whingeing about “neoliberalism” is now outdated and much off the mark.

Crucially, the Tory Party was traditionally opposed to “untrammelled free markets” and it worried about the destructive and corrosive effects of individualism and greed.

As Karl Polanyi pointed out in his classic book on The Great Transformation, the first fighters for factory and employment legislation, to protect workers from the results of reckless industrialization in the 1830s and 1840s, were from the ranks of the church and the Tory Party:

“The Ten Hours Bill of 1847, which Karl Marx hailed as the first victory of socialism, was the work of enlightened reactionaries.”1

Benjamin Disraeli

Tories like Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, were great nineteenth-century social reformers. The Tory Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli railed against selfish individualism, particularly in his novels. For Disraeli, British imperialism was more important than unalloyed individualism.

May has brought the Tory party back to its pre-Thatcher roots. But, less enlightened than Shaftesbury or Disraeli, she has little appetite for protective legislation or constitutional reform. Instead, she celebrates her own powers of leadership and seeks a mandate to concentrate power in her hands.

She has little enthusiasm for democracy either. If it were not for the heroic efforts of Gina Miller and the decision of the Supreme Court, the triggering of Article 50 – to start the process of leaving the European Union – would have been taken by the executive without a parliamentary vote.

The 2017 Tory manifesto is a maypole for nationalism. “Britain” is one of its most-used words. It says that immigration will be brought down, while existing powers by the British state to read emails and monitor your activity on the web will be increased. She will create an Internet that is controlled by the state. May is developing the infrastructure of an authoritarian nationalist regime.

Bringing the state back in: Labour’s new-old economic nationalism

At least on the surface, there are dramatic differences with Labour’s manifesto, which, for example, contains more measures targeted at the poor and elderly. Labour also gives much more verbal emphasis to human rights and democracy.

But at the core of Labour’s 2017 manifesto is a strong dose of economic nationalism, with Labour’s greatest commitment to public ownership since the “suicide note” manifesto of 1983. There are plans to bring the railways, energy, water and the Royal Mail all back into public ownership.

The 2017 manifesto declares: “Many basic goods and services have been taken out of democratic control through privatization.” But there is little explanation of what “democratic control” would mean under public ownership.

How would it work? Would parliament take decisions on everything? In reality these proposals – whatever their other merits – would enlarge state bureaucracy: there is no explanation how they would extend democracy.

The words “control” or “controls” appear 32 times in the 2017 manifesto. There is insignificant explanation of how “controls” work. The Labour manifesto envisions a concentration of economic power in the hands of the state, notwithstanding its verbal commitment to regional and local, as well as national, public management.

While there are commendable measures to enhance and enlarge an autonomous sector of worker-owned enterprises, there is little recognition of the importance of having a viable and dynamic private sector as well.

Corbyn’s Labour: forward to the past

As May has brought the Tories back to the pre-Thatcher years, Corbyn has brought Labour back to its traditional roots, before the leadership of Tony Blair.

With his 1995 changes to Clause Four of the Labour Party Constitution, Blair brought in an explicit commitment to a dynamic private sector. Labour stood for an economy where “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation”. Corbyn has returned to the spirit of Labour pre-1995 constitution, even if he has not yet changed the wording.

With his 1995 changes to Clause Four of the Labour Party Constitution, Blair brought in an explicit commitment to a dynamic private sector. Labour stood for an economy where “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation”. Corbyn has returned to the spirit of Labour pre-1995 constitution, even if he has not yet changed the wording.

Corbyn has proposed that Britain can be “better off” outside the EU. He argued that EU rules block the kind of state-heavy industrial policy that he favours. But EU countries such as France and Germany already have strong interventionist policies for industrial and infrastructural development. In truth, Corbyn favours repeated doses of statist socialism in one country.

With some Stalinist exceptions in his coterie, Corbyn and his followers are mostly sincere in their commitment to democracy and human rights. But what they do not understand is that their proposed statist concentration of economic power will undermine countervailing politico-economic forces that can help to keep the state leviathan in check.

Jeremy Corbyn and Hugo Chávez

These countervailing and separated powers are vital. Especially in times of hardship or crisis, there will be a temptation by some in power (at the local or national level) to abuse rights and undermine democracy. Every single historical case shows this result.

Attempts “to take control of the economy”, even with measures of decentralization and local power, have led to restrictions on press freedom, arbitrary detentions, abuses of human rights, and even famine.

Forward together: economic nationalists take the helm

Further doses of economic nationalism may be possible in a country as large as the United States. In 2015, exports from the USA amount to about 13 per cent of GDP. Hence economic nationalists in the USA can reduce trade without too much contraction of the economy. It may turn further inwards, cut imports and still survive a loss of exports.

But the UK has become a globally-orientated, open economy, exporting 28 per cent of its GDP in 2015. About 45 per cent of these exports go to the European Union.

By exiting the EU Single Market, and by walking away from EU trade deals with non-EU countries that benefit EU member states, Labour and the Tories would threaten the UK economy with a massive downturn. The British economy would fall off a cliff.

By exiting the EU Single Market, and by walking away from EU trade deals with non-EU countries that benefit EU member states, Labour and the Tories would threaten the UK economy with a massive downturn. The British economy would fall off a cliff.

In this crisis, rightist economic nationalists will blame foreigners and immigrants, and leftist economic nationalists will blame the rich.

It will be “the few” – designated by their ethnicity or by their assets – who will get the blame. Their rights will be under threat, as so will the liberties of all of us. Whatever variety is chosen, economic nationalism could severely undermine the viability of democracy in the UK.

21 May 2017

Minor edits – 23, 28 May, 29 June

|

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

Endnote

Bibliography

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Moore, Barrington, Jr (1966) Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World (London: Allen Lane).

North, Douglass C., Wallis, John Joseph and Weingast, Barry R. (2009) Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press).

Polanyi, Karl (1944) The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (New York: Rinehart). See esp. pp. 165-66.

Posted in Brexit, Common ownership, Democracy, Donald Trump, Immigration, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Populism, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Tony Blair, Tony Blair, Uncategorized, Venezuela

May 8th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

This is in part a personal memoir – concerning my role in a minor episode in political history. More importantly, it has lessons concerning Labour’s ideological inertia – the difficulty of modernising the party and bringing it from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century.

Socialism and Labour’s Clause Four

Both Robert Owen and Karl Marx defined socialism as “the abolition of private property”. This kind of collectivist thinking was encapsulated in Clause Four, Part Four of the Labour Party Constitution when it was adopted in 1918:

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector. Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

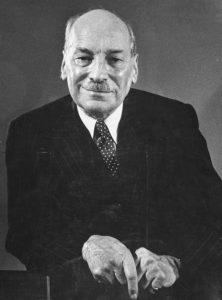

Clement Attlee

In 1937, eight years before he became Prime Minister, Clement Attlee approvingly quoted the words of Bertrand Russell: “Socialism means the common ownership of land and capital together with a democratic form of government. … It involves the abolition of all unearned wealth and of all private control over the means of livelihood of the workers.”

After 1945, the position of many leading Labour Party members began to shift. First the realities of gaining and holding on to power – as a majority party for the first time – dramatized the political and practical unfeasibility of abolishing all private enterprise. Some nationalization was achieved, but a large private sector remained.

In 1956 C. Anthony Crosland published The Future of Socialism. This sought a reconciliation with markets, private enterprise and a mixed economy. In 1959 the (West) German Social Democratic Party abandoned the goal of widespread common ownership. In the same year, Hugh Gaitskell tried to get the British Labour Party to follow this lead, but met stiff resistance. Clause Four remained intact.

Richard Toye noted that the Labour Party assumed widespread public ownership and failed to develop adequate policies concerning the private sector:

“Labour, until at least the 1950s, showed little interest in developing policies for the private sector. During the 1960s, the party demonstrated continuing ambiguity about whether or not competition was a good thing. This ambiguity continued at least until the 1980s.”

The Thatcher Revolution

There were Labour governments from 1964 to 1970 and from 1974 to 1979. But then Margaret Thatcher came to power.

After this defeat, Labour’s instinct was to turn to the left, in the belief that it could have held onto power if it had held to classical socialist principles. Michael Foot was elected as leader, and Dennis Healey narrowly defeated Tony Benn for the position of deputy leader.

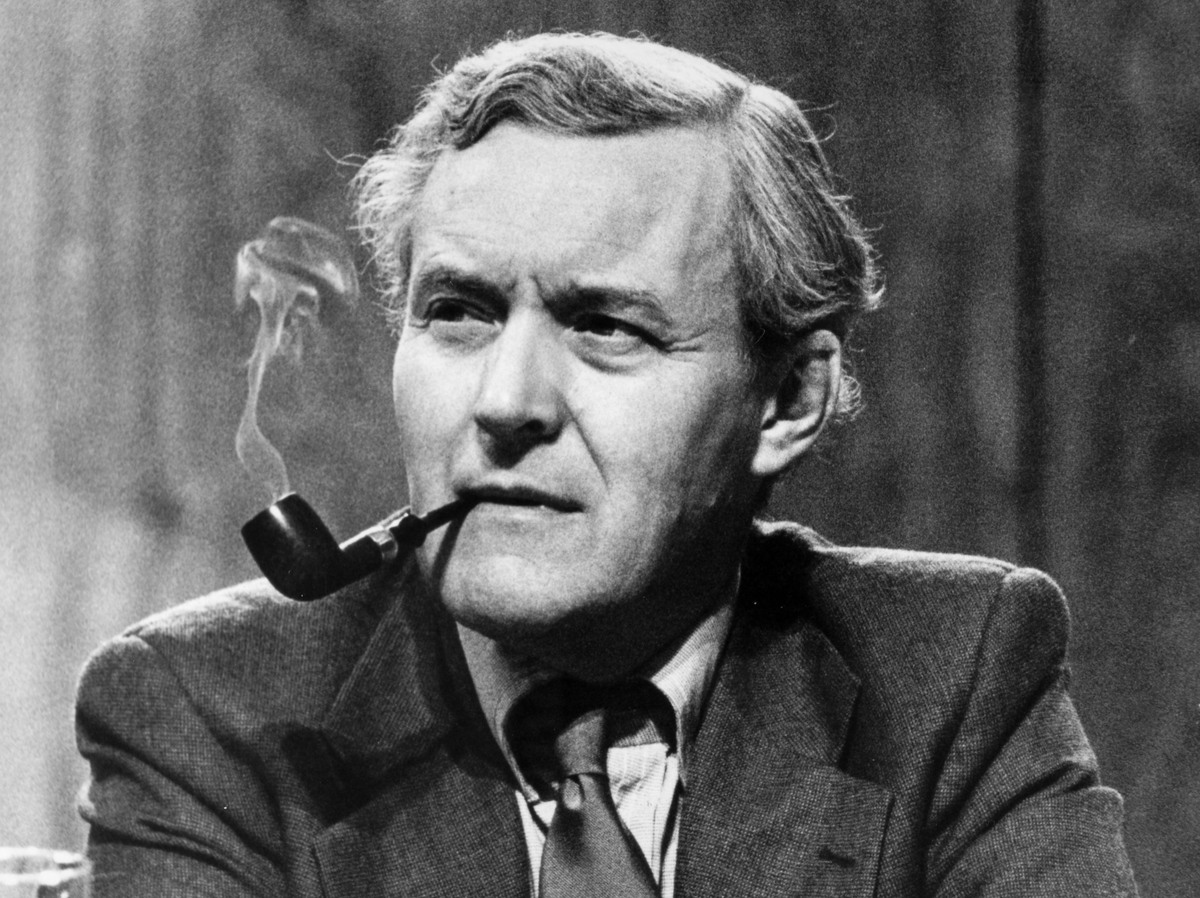

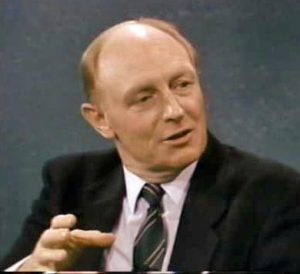

Neil Kinnock

Despite a severe recession with millions unemployed, following the implementation of monetarist austerity policies, Labour suffered a massive defeat in the 1983 general election. Labour’s share of the vote fell below 28 per cent – the party’s lowest figure since 1918. Michael Foot resigned as leader and Neil Kinnock took his place.

Thatcher had boosted her popularity due the Falklands War. One of Thatcher’s most popular domestic policies was to promote the sale of council-owned housing to the tenants. Labour had opposed this policy. The 1983 defeat prompted a rethink, on this and other issues.

Tony Benn

For some of us, this rethink amounted to more than expedient doctrinal trimming. Encouraging home ownership was really a good idea: why should all property be owned by the rich? But while supporting home ownership, we argued that the government should also build more social housing and enlarge the stock available for rent by low-income families.

But these ideas met stiff resistance in the Labour Party ranks, and not simply from Trotskyist entryists such as Militant. The resistance from Tony Benn and his supporters was substantial and even more enduring. It was clear that old-fashioned socialist ideas still had a tenacious appeal for Labour’s membership.

The Labour Coordinating Committee

The Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) became one of the primary modernising forces within Labour. Its leadership included Hilary Benn, Cherie Blair, Mike Gapes, Peter Hain, Harriet Harman and others of enduring fame. I was elected to its executive committee. We worked closely with Kinnock and members of his shadow cabinet, including Robin Cook.

I had written a book entitled The Democratic Economy where I argued that socialists should support a permanent private sector in the economy. The book was published by Penguin in 1984. Another influential work at the time was Alec Nove’s Economics of Feasible Socialism, which also argued for a substantial role for markets.

I had written a book entitled The Democratic Economy where I argued that socialists should support a permanent private sector in the economy. The book was published by Penguin in 1984. Another influential work at the time was Alec Nove’s Economics of Feasible Socialism, which also argued for a substantial role for markets.

On 26 November 1983, at the Labour Coordinating Committee AGM in Birmingham, I proposed that Clause Four of the Labour Party constitution should be rewritten to include an acceptance of a private sector and a role for markets. But I was defeated over the idea that Clause Four should be rewritten. This was out of fear of antagonising the Benn wing. Instead, the LCC resolved that Clause Four should be “clarified”.

But a resolution on long-term aims, which I had helped to draft, was passed by a large majority. The resolution called for the Labour Party to draft a new statement of aims, upholding “that socialism involves extended democracy and real equality. Democracy under socialism is extended to industry and the community … and must involve a substantial decentralisation of power.”

Equality meant the “absence of discrimination on the basis of gender and race, universal freedom from poverty, and a widespread distribution of wealth and power, as well as formal equality under the law and universal suffrage.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

There was also a “commitment to internationalism, disarmament and peace” and “a disengagement from the power blocs” of the West and East.

I think that today Jeremy Corbyn and his followers would accept much or all of this, at least as a temporary stopping-point on the road to full socialism. But in the 1980s there was strong hostility to these revisionist ideas from within Labour’s ranks at the time, including from Corbyn and Tony Benn.

Since then my own views have adjusted. See my Wrong Turnings book. But this blog is not primarily about me. It is about what has happened to the Labour Party and how difficult it is to change its DNA.

For a while, the LCC tried to keep the conversation going on the need to revise Labour’s aims. The Guardian newspaper reported the LCC conference with the headline: “Labour breaks taboo on ownership”.

The LCC held a conference in Liverpool in June 1984 on “The Socialist Vision”. But enthusiasm for this discussion fizzled out. Many leaders of the LCC wanted a political career, and they wished to widen their support on constituency selection committees.

By 1985 the LCC’s revisionist initiative had been kicked into the long grass. My efforts to change Clause Four had failed.

From Kinnock to Blair

But to their credit, Neil Kinnock and his deputy Roy Hattersley saw the need for Labour to modernise its aims. I advised them both for a while. Another election defeat in 1987 spurred a rethink. But by then I had become inactive in the Labour Party.

As Richard Toye has recorded, in 1988 Kinnock and Hattersley presented a new document on “Aims and Values” to Labour’s National Executive Committee. But “it was criticised by John Smith, Bryan Gould and Robin Cook as being too enthusiastic about the benefits of the market, and was watered down accordingly”.

Tony Blair

Clearly, even after a third election defeat there was still strong resistance, from both the “soft” and the “hard left”, to the idea of embracing markets and private property.

After the next election defeat in 1992, Kinnock stood down. He was replaced by John Smith, who died tragically from a heart attack. Then Tony Blair became leader, with a firm resolve to modernize the party. Four election defeats had made the majority of members more receptive to his ideas.

Blair’s Revision of Clause Four

In 1995, after 77 years, Clause Four was changed. Tony Blair successfully ended the Labour Party’s longstanding constitutional commitment to far-reaching common ownership. Tony Benn protested: “Labour’s heart is being cut out”. The new wording of “Clause IV: Aims and Values” began as follows:

“The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few; where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe and where we live together freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.”

The 1918 formulation did not use the word socialism – it had common ownership instead. Ironically, Blair introduced the term in 1995. But he attempted to change its meaning. He promoted “social-ism”, which now meant recognizing individuals as socially interdependent. It also signalled social justice, cohesion and equality of opportunity.

The new Clause Four continued, to make a significant statement in support of competiive markets and a private sector. Labour now stood for:

“A DYNAMIC ECONOMY, serving the public interest, in which the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation to produce the wealth the nation needs and the opportunity for all to work and prosper with a thriving private sector and high-quality public services …”

The text went on to cover “a just society”, “an open democracy”, “a healthy environment” and “defence and security”.

John A Hobson

Labour’s new aims and values were indistinguishable from the earlier views of radical social liberals, such as T. H. Green, J. A. Hobson and David Lloyd George. And with its endorsement of “the rigour of competition” and “a thriving private sector” it was a hundred miles away from the collectivism of Robert Owen and other original socialists.

Instead of tackling the problem of its old collectivist DNA more directly, Blair tried to change the meaning of socialism and even rewrote parts of its own history. It is unsurprising that the old socialist DNA survived. It remained viable, partly because Labour still declared itself as socialist. Blair made radical changes but also gave succour to the traditional socialist wing of the party.

Blair’s popularity within the party had waned even before his decision in 2003 to support George W. Bush’s Iraq War. Much of this disenchantment was due to his abandonment of wholesale common ownership.

Blair had failed to develop a fully-fledged alternative vision within Labour to replace old-fashioned common ownership. He had made Labour implicitly embrace liberalism in doctrine. But this was unspoken, and masked by the explicit insertion of socialism in its aims. This inadvertently played into the hands of the party’s enduring, backward-looking left.

Labour’s Love Lost

Just as Labour had shifted to the left after losing power in 1979, after its 2010 defeat it shifted slightly leftwards under Ed Miliband. But the new leader had no clear alternative to the economics of austerity. So after another defeat in 2015. the party membership took a massive lunge to the left. It elected the Bennite, retro-Marxist, perennial protestor, Jeremy Corbyn.

But while old ideas within Labour had survived, the structure of the party and its electoral base had changed enormously in the period from 1983 to 2015. Kinnock had relied on the moderating force of the trade unions, to fight the hard left and move the party toward electability. But by 2015 the unions had been gravely weakened and several had moved toward the hard left.

But while old ideas within Labour had survived, the structure of the party and its electoral base had changed enormously in the period from 1983 to 2015. Kinnock had relied on the moderating force of the trade unions, to fight the hard left and move the party toward electability. But by 2015 the unions had been gravely weakened and several had moved toward the hard left.

In 1983, both the affiliated unions and the Labour MPs had a major role in the election of any new Labour leader. But by 2015 the power was almost entirely in the hands of the Labour Party membership, and the other moderating forces were much diminished.

Labour’s history shows how difficult it has been to change Labour’s old-fashioned socialist DNA. Those that put their faith in a revival of moderation within must take into account the near-collapse of those internal forces that brought the party back to sanity in 1951-1964 and in 1979-1997.

In 1983 there was still a strong, traditional, tribal, Labour vote, part of it based on surviving industries such as coal and steel. By 2015 the working class was much more fragmented, with skilled, aspirational cohorts at one extreme, and uneducated, demoralized, welfare dependents at the other.

The old tribalism was challenged by UKIP and by a revived working class Conservatism, playing the nationalist card. Labour’s potential electoral base has been transformed beyond recognition. The division of labour has become profoundly political, as well as enduringly economic.

Today, there seems little hope for a party that calls itself “Labour”, just as there is no future for a party that retains the word “socialism” or the goal of widespread public ownership. The socialist experiments of the twentieth century testify to their failure. Labour, in short, is an anachronism.

8 May 2017

|

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

References

Attlee, Clement R. (1937) The Labour Party in Perspective (London: Gollancz).

Blair, Tony (1994) Socialism, Fabian Pamphlet 565 (London: Fabian Society).

Clarke, Peter (1978) Liberals and Social Democrats (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1984) The Democratic Economy: A New Look at Planning, Markets and Power (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Nove, Alexander (1983) The Economics of Feasible Socialism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Toye, Richard (2004) ‘The Smallest Party in History’? New Labour in Historical Perspective’, Labour History Review, 69(1), April, pp. 83-104.

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Property, Robert Owen, Socialism, Tony Benn, Tony Blair, Tony Blair

April 28th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

In the May 2017 run-off between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the defeated first-round candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon refused to endorse the liberal Macron over the neo-fascist Le Pen. Many of Mélenchon’s leftist supporters did the same, arguing positively for abstention.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon

The abstainers argued widely that Macron is a “neoliberal” and the voters faced a choice between the dictatorship of the market or a fascist president.

This failure to perceive any advantage of a pro-market liberal over the racist and neo-fascist authoritarian nationalism of Le Pen’s National Front, is a symptom of a deep ideological sickness that has endured for decades on the French Left.

The political degeneration of the French Left, which even exceeds that of its Corbynista counterpart in Britain, would be the subject of another blog. My purpose here is to focus on the abuse of the term “neoliberalism” and how this corrupted and overly-widened word has poisoned political discourse.

I also wish to show how some “neoliberals”, who do not include Macron, and whom I shall attempt to characterise more precisely than the n-word will allow, do indeed have connections with genuine fascism.

After the erosion of credibility in classical socialism, particularly after its failed experiments in the twentieth century, it must be understood that our sole alternative to the rising nationalisms of Le Pen, Trump, Putin, Xi, Erdoğan and others is a modern and democratic version of liberalism. Whatever his flaws, Macron fits into the latter category.

The degeneration of the “neoliberalism” label

The widespread use of the word “neoliberal” to describe anyone accepting a significant role for private property or markets has made the word so imprecise that it has become useless and beyond reform.

Even the foremost historians of “the neoliberal project” have acknowledged the problem. Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe wrote:

Even the foremost historians of “the neoliberal project” have acknowledged the problem. Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe wrote:

“We can sympathize with the impatience for those who use the term ‘neoliberalism’ as a blanket swearword for everything they despise, or a brainless synonym for modern capitalism.”

Colin Talbot pointed out that “neoliberalism” has become “a term of abuse” to be used against “any type of pro-market reform or political position that recognizes markets may – in the right circumstances – be a good thing”. Consequently, everyone “from moderate social democrats to the most lurid free-marketeers gets lumped together under a convenient ‘neoliberal’ label.”

In a superb survey of its usage since the 1980s, Rajesh Venugopal concluded that “neoliberalism has become a deeply problematic and incoherent term that has multiple and contradictory meanings, and thus has diminished analytical value.”

Some may wish to retain the “neoliberal” label, to apply it to those free marketeers who attempt to shrink radically the size of the state, to privatise anything that walks, advocate economic austerity and deregulate the financial sector. This would certainly separate neoliberalism from the genuine liberalism of John A. Hobson, William Beveridge or John Maynard Keynes.

But I think that things are too far gone to allow any useful redefinition of the “neoliberal” label to succeed. It is perhaps best abandoned. Instead I wish to focus on a particular strain of so-called “neoliberalism”. This allows us to concentrate on some key issues.

Ludwig von Mises and fascism

Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) and Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992) were key figures in the so-called Austrian school of economics. Among their major achievements were their contributions to the “socialist calculation debate” where they showed the practical and epistemic limitations of any system of national planning based on comprehensive public ownership.

Ludwig von Mises

While sharing with liberals the support for a market economy based on private ownership, von Mises and Hayek departed from both classical liberalism (of John Stuart Mill, for example) and from twentieth-century liberalism (of John A. Hobson, John Dewey and John Maynard Keynes, for example), in some important respects.

In a book originally published in 1927, Ludwig von Mises praised fascism as “an emergency makeshift” that “has, for the moment, saved European civilization”. This statement cannot be excused, despite the facts that it was in a book that was otherwise devoted to the promotion of classical liberal values, and that von Mises was a Jew who eventually had to flee the Nazis.

From 1932 to 1934 von Mises continued as an economic adviser in Austria, even to the “Austro-fascist” or “clerical fascist” government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, who assumed dictatorial powers, closed down parliament, smashed the trade unions, and banned several political parties. This does not mean that von Mises was a fascist, but other economists would have drawn the line at advising them.

Friedrich Hayek and the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet

Friedrich Hayek

The idea that temporary dictatorships, even if murderous, might sometimes be necessary rubbed off onto von Mises’ student, Friedrich Hayek. Hayek argued that democracy, while desirable, can be temporarily dispensable, particularly in defence of private property.

Augusto Pinochet may have saved private property rights in Chile. But he imposed a vicious dictatorship that tortured an estimated thirty thousand civilians and murdered over three thousand.

The right to life, and freedom from torture, are existentially more basic, and hence even more important, than the right to property. Hayek visited Pinochet’s Chile and he failed to condemn these atrocious abuses of human rights. Hayek’s silence over abuses of basic human rights cannot be excused by his age: he was still publishing major books in the 1970s.

The twentieth century teaches us that Marxist socialism crushes human rights and leads to dictatorship. While opposing Communism, von Mises and Hayek (temporarily) tolerated some dictatorships and their removal of some basic human rights, including the rights of habeas corpus and to live without torture.

While earlier liberals had emphasized human rights, private property rights and democracy, in their reaction against socialism, von Mises and Hayek seemed to elevate private property rights over everything else. But private property rights require the protection of all actual or potential owners from torture or extermination. Basic human rights and democracy are vital, as well as the right to private property.

The Mont Pèlerin Society

The ideas of Mises and Hayek were prominent in the Mont Pèlerin Society, founded in Switzerland in 1947. The society accommodated a variety of views, including mainstream liberals plus some members who had collaborated with Nazism in the 1933-1945 period.

The Mont Pèlerin Society was dominated by economists. No less than eight winners of the Nobel Prize in economics have been its members.

The Mont Pèlerin Society was dominated by economists. No less than eight winners of the Nobel Prize in economics have been its members.

The influence of economists is evident in the draft statement of aims of the Society. It opened with these words:

“Individual freedom can be preserved only in a society in which an effective competitive market is the main agency for the direction of economic activity. Only the decentralization of control through private property in the means of production can prevent those concentrations of power which threaten individual freedom.”

Agoraphobics (i.e. fearers of markets) such as George Monbiot and Naomi Klein will probably disagree, but there is a vital truth in this quotation.

The trouble is that it is also a half-truth. Private property and markets are necessary but insufficient to guarantee liberty, as countless market-based totalitarian regimes, from Putin’s Russia to Pinochet’s Chile, will testify. The Mont Pèlerin statement should have made this clear. Instead it gave licence to a view that only private property and markets matter.

Margaret Thatcher and Augusto Pinochet

Hence Mont Pèlerin fans, including UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan, supported dictatorships and opposed sanctions against South African Apartheid.

In 1999, Thatcher even thanked the former dictator Pinochet for “bringing democracy to Chile”. Clearly, while addressing someone who in 1973 overthrew a democratically-elected government, she invested the term “democracy” with an esoteric, Thatcherite meaning. In truth, Pinochet was a torturer and an assassin.

Vital differences between liberalism and Mont Pèlerin neoliberalism

Even with this brief account we can see some wide, clear water between mainstream liberals such as Macron and Mont Pèlerin “neoliberals” such as Hayek. Unlike those “neoliberals”, modern liberals uphold the following five points:

-

While markets and private property are essential, they are not sufficient to guarantee human rights and liberty. Vigilance and debate, within a democratic system with a free press, are necessary as well.

-