Category: Democracy

January 28th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

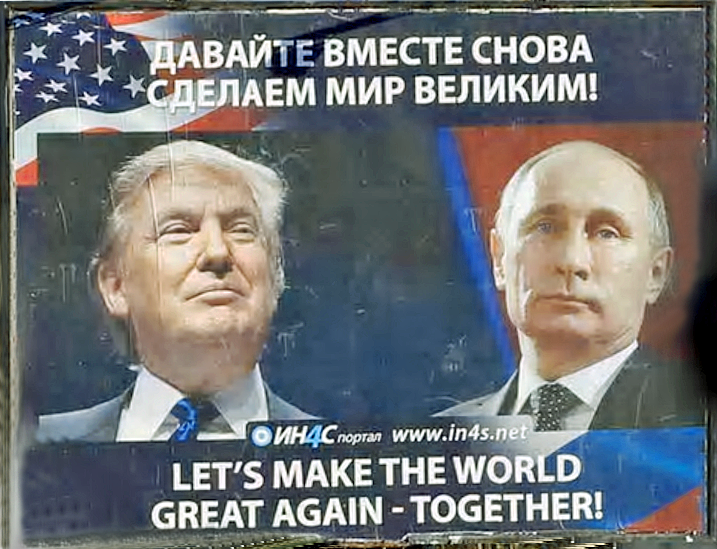

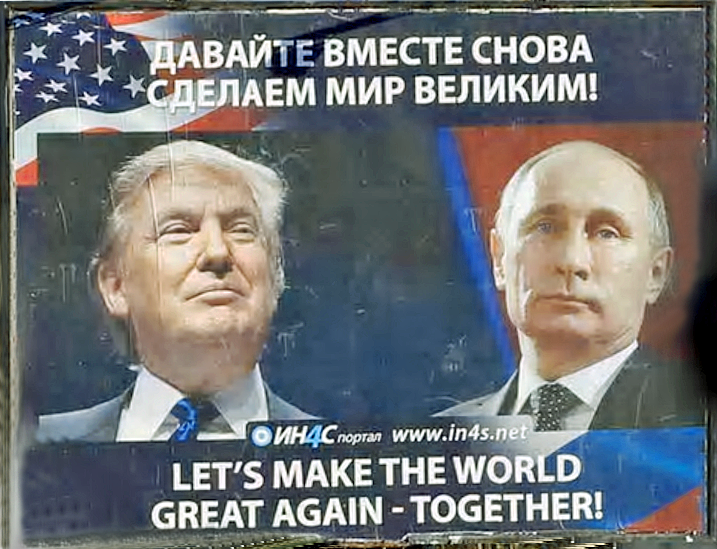

The political earthquakes of 2016 are probably the beginning of a series of major ruptures in world politics. Donald Trump was elected in the USA, Britons voted for Brexit, Turkey lurched toward dictatorship, Brazil ejected a democratically-elected president, Russia extended its global influence, and China tightened internal security while building military bases in the South China Sea.

From America to Asia, authoritarian nationalism is on the march. The future of old alliances is cast in doubt, raising a renewed spectre of global war.

These seismic changes should prompt us to reconsider our priorities. Is ‘neoliberalism’ – whatever that means – our main enemy? Or is it rising authoritarianism and nationalism instead?

We have been here before, albeit with much less dangerous military weapons. The rival imperialisms of the nineteenth century led to the First World War. Collapsing imperial dynasties triggered revolution in Central and Eastern Europe. Communists successfully seized power in Russia in 1917. Post-war political and economic turbulence led to the triumph of fascism in Italy, Germany and Spain. Imperial Japan invaded nationalist China.

I am not suggesting that history will repeat itself in the same way. But it is important to understand how the tectonic plates of political change affected the way we understand and map political positions, and the way in which we prioritise political issues.

The thirty-year squeeze (1918-1948)

Europe suffered economic depression for much of the interwar period. The financial crash of 1929 exacerbated the crisis and led to a collapse of world trade. Liberal defenders of the market economy were put on the defensive: capitalism seemed at the end of its tether.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Meanwhile, some intellectuals from the USA and Britain – including Labour stalwarts George Bernard Shaw and Sidney and Beatrice Webb – visited the Soviet Union brought back glowing accounts of an expanding economy and a joyful population. (The Soviet propagandists explained away disasters such as the Ukranian Famine as resulting from sabotage by rich peasants or foreign agents.)

With the crisis of capitalism, the rise of fascism and the apparent success of Soviet Russia, many British and American radicals became Communists or fellow travellers. For them, liberalism and the defence of the market economy seemed a weak or unviable option.

The choice seemed to be between two forms of authoritarian government: much better the one that proclaimed equality and opposed racism. (But in reality, the Stalin regime promoted antisemitism, genocide against several other ethnic minorities, and dramatic internal inequalities of power.)

Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill in 1941

The alliance between Russia and the West in the Second World War smothered criticism of what was really going on within Stalin’s regime. But, with the beginning of the Cold War in 1948, socialists were forced to make a choice between either supporting an antagonistic and undemocratic foreign power, or aligning with the USA and its allied democracies.

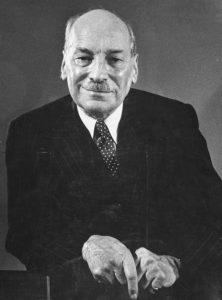

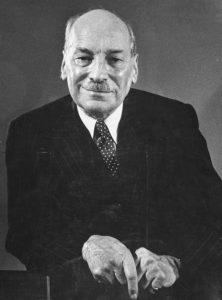

Labour under Clement Attlee aligned with the West. But rose-tinted visions of Soviet Russia or (from 1949) Mao’s China lived on among he Left.

In major European democracies, the thirty years between the end of the First World War and the start of the Cold War had seen liberalism squeezed, between socialism on the one hand, and reactionary authoritarianism on the other.

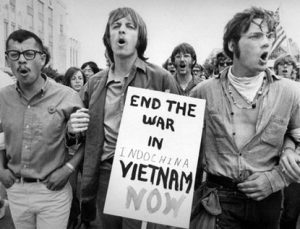

‘American imperialism’ and the rise of neoliberalism

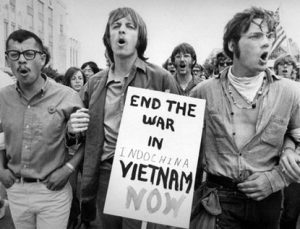

Things were different in the USA, which polarised between forms of Republican conservatism and Democratic liberalism. But rising tensions in the Cold War, and the eruption of the Vietnam War in the 1960s, made American-style liberalism less attractive for the global Left.

Marxist-led national liberation movements in Cuba, Indochina and elsewhere kept the collectivist vision alive for the Left around the world. Liberalism was see as the fake ideology of American imperialism and the global bourgeoisie.

Marxist-led national liberation movements in Cuba, Indochina and elsewhere kept the collectivist vision alive for the Left around the world. Liberalism was see as the fake ideology of American imperialism and the global bourgeoisie.

Some have argued that neoliberalism was reborn in the 1970s, when conservatives such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher adopted a vision of expanding markets and a contracting state. Although the Left could never agree on what ‘neoliberalism’ meant, they mostly agreed that it was the main enemy.

Much of the Left, throughout the world, had never got rid of its agoraphobia – its fear of markets. Private enterprise and market forces were always and everywhere seen as the problem. Liberals, who defended private property and markets as well as human rights, were mocked as the bourgeois enemy.

Our brave new world

But the global tectonic plates are now shifting abruptly, in an erupting national and international crisis, as big as anything since 1948.

Nationalist leaders strut around the world stage. They stock up their nuclear and conventional arsenals and jostle for geopolitical advantage.

Torture is endorsed. Journalists are threatened or imprisoned. Scientific findings on climate change are denied. Intellectuals and experts are ridiculed. Ignorance and dogma are celebrated. Truth is swamped by lies. Legislation protecting workers and the poor is undone. Minorities are attacked and made scapegoats. Racism is given licence. People suffer discrimination on the basis of their religious or other beliefs. Democratic systems are damaged. Judges and lawyers are treated as traitors. The rule of law is undermined.

In this dangerous new world, it matters less whether that railway is nationalised or whether water distribution is in public ownership. Forms of ownership are always secondary to the actual provision and distribution of vital goods and services. But when our rights and liberties can no longer be taken for granted, questions over forms of ownership move even further down the ranking of priorities.

The ubiquitous, trivialising idea that the Left is defined in terms of public provision, and Right as private provision, is historically recent and a gross reversal of their original meanings. It is also a polarisation of lesser relevance in this world of rising authoritarian nationalism.

Our fundamental rights, our liberty, and the rule of law are now increasingly threatened. Their defence becomes the great struggle of our time.

This lesson is hardest for Americans and Britons, who were spared domestically from the jackboots of twentieth-century despotism. Struggles for British and American national liberty are beyond living memory. We have grown fat and lazy on the fruits of the liberal order. We have taken for granted its institutions and underestimated their fragility. We must repair our vigilance.

The liberal opportunity

For 100 years, for the reasons given above, liberalism has been marginalised. Now is its opportunity – indeed its urgent necessity.

Unlike our grandparents in the crisis-ridden 1930s, we have seen the socialist experiments of the twentieth century and counted their cost at 90 million lives. History and social science have more to teach us. If we wish to learn, we can know more about how markets work. We can understand the informational, organisational and other impediments to comprehensive national planning. We can appreciate why countervailing politico-economic power, based on a strong private sector, are necessary to buttress democracy and resist authoritarianism. The twentieth century has taught us these lessons.

The old Marxist mantra of bourgeoisie versus proletariat is also ungrounded in reality. Instead we have a highly fragmented working class, much of it enduringly aligned with authoritarianism and nationalism. Marxism relies on a quasi-religious and nonsensical belief that the working class – whatever it actually believes or strives for – carries our human destiny.

Class struggle has mattered, but it has never been the main motor of history. What have mattered more have been struggles for power, by individuals, dynasties, nations, religions or ideological movements.

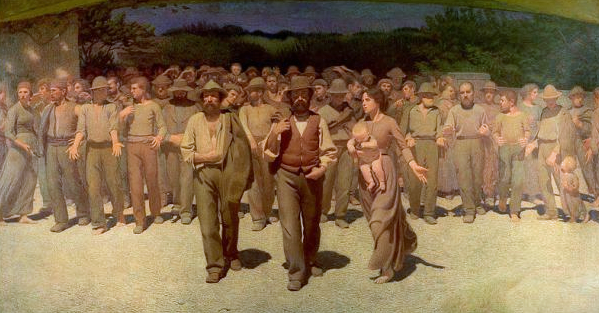

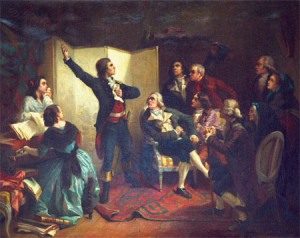

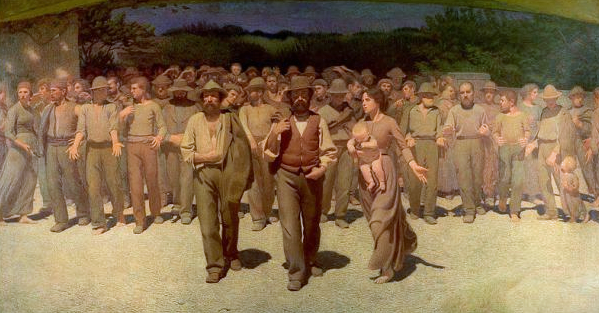

The Storming of the Bastille in 1789

Liberalism was one of those movements. Based on the imperatives of equality and liberty, it matured in the Enlightenment.

Liberalism rose up in the English Civil War of the 1640s, in the American Revolution of the 1770s, and in the French Revolution of 1789, in titanic struggles against despotism and oppression.

Now, once again, liberalism is centre stage, as the enemy of authoritarian nationalism.

The liberal rainbow

Its allies are not those who pander to authoritarianism by eroding civil liberties, or do the spadework of the nationalist Right by making immigration (rather than assimilation) a foremost problem. The prime allies of liberalism are all those who defend liberty and human rights. But therein lies a concern, which must be discussed.

From the beginning, liberalism has harboured different views on the role of the state and of the degree of state intervention required in the economy and society. On the one hand there are liberals – sometimes called libertarians – who wish to minimise the role of the state.

Thomas Paine

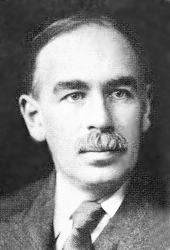

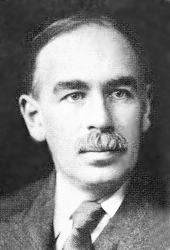

John Maynard Keynes – another great liberal – argued that state regulation of financial markets and counter-cyclical expenditures are necessary to stabilise the capitalist system. Keynes showed that economic austerity is a flawed doctrine. Government deficits are best reduced by growth: budget cuts can contract the entire economy and make the problem worse.

There is a spectrum of views between individualist and social-democratic liberalism, but all liberals are united in their defence of individual liberty, human rights and political democracy. The diverse colouring of this rainbow does not diminish its united opposition to the dark intolerance and division that is exacerbated by authoritarian nationalism.

The struggle for liberty and equality has always been vital. But many twentieth-century radicals were diverted by the delusions of socialism. The renewed rise of authoritarianism has shown us again that liberalism is the vital political movement of the modern age.

28 January 2017

Minor edits: 29 January, 1, 16 May 2017

|

This book by G. M. Hodgson elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

Bibliography

Allett, John (1981) New Liberalism: The Political Economy of J. A. Hobson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Beveridge, William (1944) Full Employment in a Free Society (London: Constable).

Clarke, Peter (1978) Liberals and Social Democrats (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Claeys, Gregory (1989) Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (London and New York: Routledge).

Courtois, Stéphane, Werth, Nicolas, Panné, Jean-Louis, Packowski, Andrzej, Bartošek, and Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999) The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Keane, John (1995) Tom Paine: A Political Life (London: Bloomsbury).

Keynes, John Maynard (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Macmillan).

McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen (2017) ‘Nationalism and Socialism Are Very Bad Ideas: But liberalism is a good one’, Reason.Com, February. http://reason.com/archives/2017/01/26/three-big-ideas

Monbiot, George (2016) ‘Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems’, The Guardian, 15 April. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot.

Townshend, Jules (1990) J. A. Hobson (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Venugopal, Rajesh (2015) ‘Neoliberalism as a Concept’, Economy and Society, 44(2), pp. 165-87. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013356.

Posted in Brexit, Common ownership, Democracy, Donald Trump, Immigration, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Populism, Private enterprise, Right politics, Socialism

December 6th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Racist nationalism has returned from the fringes to mainstream politics. In 2016 it played a major role in the Brexit vote in the UK, in the election of Donald Trump in the US, in the presidential election in Austria, and in developments in many other countries.

Racism and other forms of discrimination, including by gender or belief, must be defeated. The Left has played a major role in countering racism, and it should be give due credit for that. But in some other respects the Left on this issue is weak and misguided.

Some things we cannot talk about – but we must

Some things have become difficult to discuss. I once tweeted the (obviously true) statement that “Islam is religion, not a race”. A fellow tweeter immediately assumed that I was some kind of bigot and responded “ugh!”

In this reactive climate it has become difficult to raise concerns about (say) Sharia law without being branded racist or right-wing. Discussion ends. But the fact that rightist bigots – such as Nigel Farage and Geert Wilders – go on about Sharia law does not mean that we cannot discuss it.

Of course, Muslims and others suffer significant discrimination, in Britain and elsewhere. In recent months, Trump has been responsible for major anti-Muslim outbursts and has whipped up violent anti-Muslim sentiment in the US.

Of course, Muslims and others suffer significant discrimination, in Britain and elsewhere. In recent months, Trump has been responsible for major anti-Muslim outbursts and has whipped up violent anti-Muslim sentiment in the US.

We must defend the full human rights of everyone, including members of all faiths. But this does not mean that we must refrain from criticising religious doctrines.

On the contrary, our failure to discuss these issues has favoured conservatives over reformers within these religions, has allowed religious extremism to ferment, and has repeatedly played into the hands of the reactionary and extremist Right.

I explain here where and how the Left has got things wrong in this area. I concentrate mostly on the moderate Left. The sins of many on the Far Left are much worse, including their support for fanatical, religious, “anti-Imperialist”, extremists in Palestine, Iran and elsewhere.

The election of Trump is a wake-up call. We need to find more effective ways to counter racism and other forms of discrimination. We need to find ways to make multi-religious and multi-ethnic communities more inclusive and cohesive.

Immigration – beyond the numbers game

The recent massive increases of immigration into Europe and elsewhere are a fact. But at least as far as the UK is concerned, it has been shown that the economic benefits of immigration are positive.

But much of the political debate is about immigrant numbers. The Tories ignore the economic evidence and start a Dutch auction of targets, to stem numbers. A large part of the Labour Party, facing a seepage of its working class support to UKIP, moves in a similar direction.

But much of the political debate is about immigrant numbers. The Tories ignore the economic evidence and start a Dutch auction of targets, to stem numbers. A large part of the Labour Party, facing a seepage of its working class support to UKIP, moves in a similar direction.

Of course, mass immigration becomes a problem when there are not enough school places, health services are severely stretched, housing is limited and inadequate, and the transport infrastructure groans from decades of under-investment.

Labour is internally divided between those that want to restrict immigration, and the leadership around Jeremy Corbyn who propose no restrictions at all. With some notable exceptions, what is missing is a discussion prioritising assimilation.

The Casey Review

Louise Casey

The recently-published, government-commissioned report by Louise Casey suggests that “the tough questions on social integration are being ducked”. Casey and her team found evidence that black and minority ethnic groups are still suffering from discrimination and disadvantage and responses by government and others are inadequate. While she found some evidence of integration, in other areas the outcomes were different:

“In some council wards, as many as 85% of the population come from a single minority background, and most of these high minority concentrations are deprived Pakistani or Bangladeshi heritage communities.”

These concentrated enclaves are more difficult to assimilate and create particular problems for women:

“this sense of retreat and retrenchment can sometimes go hand in hand with deeply regressive religious and cultural practices, especially when it comes to women. These practices are preventing women from playing a full part in society, contrary to our common British values, institutions and indeed, in some cases, our laws. … I’ve met far too many women suffering the effects of misogyny and domestic abuse, women being subjugated by their husbands and extended families. Often, the victims are foreign-born brides brought to Britain via arranged marriages. They have poor English, little education, low confidence, and are reliant on their husbands for their income and immigration status. They don’t know about their rights, or how to access support, and struggle to prepare their children effectively for school.”

Casey argued that fears of being labelled “racist” have prevented society from challenging sexist, misogynistic and patriarchal behaviour in some minority communities. Her report cites claims that some Sharia councils had supported the values of extremists, condoned wife-beating, ignored marital rape and allowed forced marriages.

Her report concluded with a rallying cry:

“The problem has not been a lack of knowledge but a failure of collective, consistent and persistent will to do something about it or give it the priority it deserves at both a national and local level.”

But to “do something about it” requires a clearer understanding of the problems involved and what kind of policies are needed to deal with them. Some people have criticised Casey’s empirical claims and more research is clearly required.

Multiculturalism

As several authors have pointed out, multiculturalism is an ambiguous concept. In one sense, at least, it is unobjectionable. All civilisations have drawn and benefitted from cultural variety. Western countries today benefit enormously from the influx of ideas, skills, fashions, cuisines and experiences that successive waves of immigration have brought. This has been true for millennia. It is no less true today.

Institutions are the stuff of society: institutions are systems of social rules. Some rules – concerning dress and fashion for example – can change profoundly without social collapse.

Other institutions – particularly in law and politics – are the outcomes of centuries of experience, deliberation and experimentation. We cannot put these in a culture-mixing food blender without tearing apart the fabric of society and wrecking social cohesion and solidarity.

Much discourse about multiculturalism ignores these differences in types of rules and institutions. Everything is placed under the vague and overly-capacious category of “culture”, assuming everything can be mixed at will. This soup-making, food-blender approach is dangerous and misconceived.

Cultural relativism

Some parts of the Left have embraced normative cultural relativism. This is the view that one person’s morality is as good as any other. It is said that there is no “objective” or “correct” morality. No overriding importance is given to democracy or to the United Nations Declaration of Universal Human Rights. Other cultures have different codes and priorities: let them be.

According to this view, asking people from other cultures to adopt our over-arching laws and values is seen as a manifestation of “oppression” or “Western imperialism”. We have to be very careful not to jump to the conclusion that Western moral values are superior. But that does not mean that we should reach no judgmental conclusion at all.

Germaine Greer

For example, in her 1999 book The Whole Woman, the self-declared “Marxist” and iconic feminist Germaine Greer asked us to refrain from criticising female genital mutilation, on the grounds that it would impose our cultural values on others.

In his excellent book What’s Left? Nick Cohen gives some further examples of highly misguided cultural relativism, including attempts by feminists and leftists to defend the Indian practice of burning widows alive after the deaths of their husbands.

Analytically, this kind of cultural relativism has major flaws. First, it falls down in dealing with changing attitudes through time in one country. A cultural relativist, time travelling back to 1800, could raise no objection to slavery, or to the lack of women’s rights. If one morality is as good as any other, then there can be no moral force for change.

Second, it is internally inconsistent. Cultural relativism denies that our values are valid or suitable for other cultures. Why should this normative claim (that we should not impose our normative values on other cultures) be adopted by others in different cultures? By the logic of cultural relativism, thinkers in other cultures are not obliged to be cultural relativists. The whole argument is self-defeating.

Third, cultural relativism degrades the role of morality, by treating it as a matter of individual preference. The whole point about morality is that it transcends individual preferences. Moral claims (be they right or wrong) are universal. Humans have developed systems of morality to provide us with rules that help social cohesion while simultaneously protecting individual rights and liberties.

Reticence to act – condemnation of action

As well as the benefits of cultural enrichment, mass immigration has also brought problems of assimilation. In the UK there are large communities where many people do not speak English, or remain ignorant of prevailing laws and values that have evolved over centuries to keep our society together and to protect our interests.

Many of these immigrants had limited experience of any Western-style democracy and had an inadequate appreciation of universal human rights. Many came from rural areas in undeveloped countries, where the state was weak and social and business interactions were governed by custom and religion, based on ties of loyalty to family and clan.

Ann Cryer

Faced with this issue, many progressive politicians have adopted a stance of ultra-tolerance and inaction. Consider the question of language. Should immigrants be obliged to learn the language of their new country, so that they can understand its culture and its laws? Some other countries take this on board.

But such an assimilationist policy in the UK was highly controversial as late as 2001. In that year, the Labour MP Ann Cryer bravely argued that many Muslims were held back economically and educationally by language difficulties. The problem was especially severe among Muslim women.

But she was faced with criticism and scorn from the Left. Shahid Malik, then a senior member of the Commission for Racial Equality and of the Labour Party National Executive Committee, and subsequently a Labour MP and government minister, responded to Cryer: “Her arguments are sinister and they have no basis in fact … she is doing the work of the extreme right wing.”

Promoting faith schools

Schooling must be central to any viable integration programme. Young people need to learn about the struggles for democracy, independence, rights and human emancipation, throughout the world. They should be free to discuss and evaluate all these things.

Such a broad education is less likely in a school that is linked to one particular religion. Instead it would be more viable in secular schools with pupils from multiple religions, classes and cultures. Broad-based secular education is even more vital in multi-cultural and multi-faith societies.

After coming to power in 1997, Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair promoted a programme of expansion of faith schools. But a 2001 report commissioned by Bradford City Council concluded that its communities were becoming increasingly isolated along racial, cultural and religious lines, and that faith-segregated schools were fuelling the divisions.

After coming to power in 1997, Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair promoted a programme of expansion of faith schools. But a 2001 report commissioned by Bradford City Council concluded that its communities were becoming increasingly isolated along racial, cultural and religious lines, and that faith-segregated schools were fuelling the divisions.

In 2001 there were riots in Bradford, which spread to other northern cities. Yet in the same year the Labour Government proposed a large increase in the number of state schools run by religious organizations.

By 2002 there was a major public row, with accusations that some pupils were being taught creationism in and that homosexual acts are against God’s law. Campaigners for women’s rights expressed concern that conservative religious teachers were instructing young girls that women should take a secondary role in society.

Despite his previous opposition to Blair, in 2016 the Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn expressed his support for faith schools. No major UK political party has dared to come out against them. They are being vigorously promoted by the current Conservative government.

Faith schools have hindered assimilation

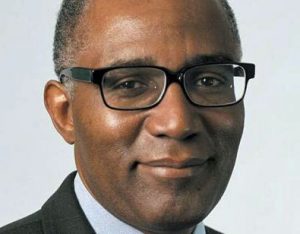

David Bell

David Bell warned in a January 2005 speech to the Hansard Society – when he was Chief Inspector of Schools – that a traditional Islamic education did not equip Muslim children for living in modern Britain. He said: “I worry that many young people are being educated in faith-based schools, with little appreciation of their wider responsibilities and obligations to British society.” He continued:

“We must not allow our recognition of diversity to become apathy in the face of any challenge to our coherence as a nation … I would go further and say that an awareness of our common heritage as British citizens, equal under the law, should enable us to assert with confidence that we are intolerant of intolerance, illiberalism and attitudes and values that demean the place of certain sections of our community, be they women or people living in non-traditional relationships.”

Trevor Phillips

His comments were condemned as “irresponsible” and “derogatory” by some senior Muslims, but supported by Trevor Phillips, then chair of the Commission for Racial Equality.

In another lecture Bell said: “We can choose … whether we want to bring our diversity together in a single rainbow or whether we allow our differences to fester into separate cultures and separate communities.”

Phillips came to the conclusion that increasing self-segregation of British communities along ethnic and religious lines was a major threat to national integration and to Enlightenment values. Young people were being brought up with insufficient awareness of these values, in closed communities where extremism could fester.

David Miliband

Ken Livingstone, then Mayor of London, attacked Phillips for “pandering to the right”. During a televised discussion, the prominent Labour Minister David Miliband shook his head and described Phillips’s remarks about community segregation as “fatuous”.

Since then, Phillips’s concerns about social segregation in British communities have been vindicated by several experts, while other evidence indicates a small amount of progress. Even the most optimistic reading of the evidence suggests a serious and enduring problem.

On faith schools, the Casey report noted their role in institutionalising segregation:

“The Government had attempted to alter the segregation of pupils in faith schools by introducing admissions criteria for new faith-based Free Schools. But these did not seem to be having an impact on the diversity of minority faith schools … [their] admission policies do seem to play a role in reinforcing ethnic concentrations.”

But Casey did not take the final step. She wrote: “ending state support for all faith schools would be disproportionate”. But how serious do the problems have to become before it becomes proportionate?

Rather than relying on failed palliatives, state-funded faith schools should be phased out. Taxpayers should not subsidise religion: religion and the state should part company.

A recent poll found that an overwhelming majority of the British public opposed religious discrimination in faith school admissions. Making all faith schools non-discriminatory in terms of religion would be a big positive step.

Fostering extremism

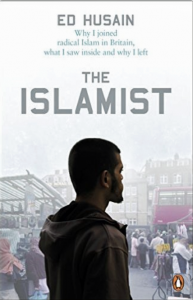

Ed Husain was born and educated in Britain, where he obtained a Master’s Degree. He was drawn toward extreme versions of Islam and was persuaded that Western democracies are irredeemably corrupt and must be replaced by a theocracies based on Islamic law.

After several years he renounced his former extremism, but retained his Islamic faith. In an interview he revealed the segregated life of his upbringing:

After several years he renounced his former extremism, but retained his Islamic faith. In an interview he revealed the segregated life of his upbringing:

“The result of 25 years of multiculturalism has not been multicultural communities. It has been mono-cultural communities. Islamic communities are segregated. Many Muslims want to live apart from mainstream British society; official government policy has helped them do so. I grew up without any white friends. My school was almost entirely Muslim. I had almost no direct experience of ‘British life’ or ‘British institutions’.” (Quoted in Cohen 2007, p. 378.)

British policy-makers have welcomed diversity. But they have defined needs and rights via the ethnic categories into which people were placed, using those divisions to shape public policy. The result has been a more fragmented society, which has nurtured extremism.

In the name of multi-culturalism, Britain has become a more divided society, where inclusive, universal, Enlightenment values are often side-lined or unknown. These communal enclaves, found in France and Belgium as well as Britain, have become hothouses for violent extremism.

Hassan Butt was born in Luton in England in 1980. In 2000 he travelled to Pakistan and worked for the Taliban and other jihadists against the West. Subsequently he renounced his anti-Western views.

Butt explained that “Islamic theology, unlike Christian theology, does not allow for the separation of the state and religion … [they] are considered to be one and the same.” Consequently, since there no righteous Islamic state is deemed to exist, the extremists have “declared war on the whole world”.

Some on the Far Left disowned Butt for betraying the struggle against “Western imperialism”. He was also criticized by one member of the “Stop the War” movement, who is a leading supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood, for his “call to change the face of Islam” (Cohen 2007, pp. 371-2).

Some on the Far Left disowned Butt for betraying the struggle against “Western imperialism”. He was also criticized by one member of the “Stop the War” movement, who is a leading supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood, for his “call to change the face of Islam” (Cohen 2007, pp. 371-2).

Butt’s response was clear: “I believe that the issue of terrorism can be easily demystified if Muslims and non-Muslims start openly to discuss the ideas that fuel terrorism.” However, many on the Left, as well as the Right, are not helping this process.

British values?

Successive British Prime Ministers have reacted to the threat of Islamist extremism by calling for “British values”. After claims that some schools in Birmingham were promoting Islamist extremism, in 2014 the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron outlined plans to put the promotion of “British values” at the heart of the national curriculum for schools. This is now official policy:

“Schools should promote the fundamental British values of democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs.”

But the official government document outlining this policy mentions respect and tolerance for other races but fails to mention discrimination against women or gays. It rightly mentions the freedom to “choose and hold” any faith, but not the freedom to exit a religion without sanction. It mentions “individual liberty” only once, and fails to uphold freedom of non-violent expression, including when it may cause offence.

But the official government document outlining this policy mentions respect and tolerance for other races but fails to mention discrimination against women or gays. It rightly mentions the freedom to “choose and hold” any faith, but not the freedom to exit a religion without sanction. It mentions “individual liberty” only once, and fails to uphold freedom of non-violent expression, including when it may cause offence.

Are these omissions an accident, or are they designed not to offend a particular religious minority?

Another problem here is not the values as such, but their nationalistic description as “British”. Democracy was not invented in Britain: Ancient Athens and Viking Iceland have much earlier precursors. The US and France have much earlier claims to the values of liberty and religious tolerance. Britain legally discriminated against Protestant nonconformists and Catholics until the nineteenth century, and it still bars any Catholic from becoming its sovereign.

Another problem here is not the values as such, but their nationalistic description as “British”. Democracy was not invented in Britain: Ancient Athens and Viking Iceland have much earlier precursors. The US and France have much earlier claims to the values of liberty and religious tolerance. Britain legally discriminated against Protestant nonconformists and Catholics until the nineteenth century, and it still bars any Catholic from becoming its sovereign.

Apart from being misleading and inaccurate, the label of “British values” would hardly be effective in preventing a young Muslim from being radicalised. On the contrary, the label can help bolster the misperception that Britain and the rest of the West are at war against Islam. This nationalistic labelling readily allows the distortion that “British values” are being promoted by the UK authorities in a global effort to counter Islam.

It would be more accurate and effective to label values such as democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and freedom of worship as “universal values” or “Enlightenment values”. They are not simply values that British residents and citizens should adopt. Other countries should promote these values too.

Islamophobia?

Polly Toynbee is a leading progressive, and vigilantly anti-racist, British journalist. Yet in 2004 she was proclaimed by the Islamic Human Rights Commission as the winner of their “Most Islamophobic Media Personality” award.

Polly Toynbee

In her words, she received this ridiculous appellation because she “had challenged the legitimacy of the idea of Islamophobia and warned of the danger to free speech of trying to make criticism of a religion a crime akin to racism.” She rightly noted that the “occasional note of reason from moderate Islamic groups is so weak it hardly makes itself heard”. She highlighted the difficulties involved in starting a serious dialogue on this issue.

The failure to distinguish racism from criticism of religion sadly remains widespread. Many on the Left have done excellent work since the 1970s in campaigning against racism, fascism and discrimination. But the frequent confusion of criticism of religion with racism has diverted their efforts.

It must be repeated that concerns about Islam as a belief system are not equivalent to bigotry toward Muslims. Racism and persecution of Muslims are serious problems and should be vigilantly opposed. But the option to criticise Islam, or any other belief system, is an important right, and it should be protected.

The term “Islamophobia” is partly to blame. Despite widespread usage, it is rarely defined and there is no consensus on its definition.

Does it literally mean fear of Islam? Or criticism of Islam? Or hatred of Islam? Or persecution of Muslims? Its intended meaning can range from scholarly criticism of Islamic doctrines to racist acts against ethnic groups who are Muslim. These are obviously very different. Yet they are all lumped together under the same label.

“Anti-Muslim prejudice” or “anti-Muslim discrimination” would be much better terms. They accurately describe this very real and sadly widespread problem.

Criticism of religion can be enlightening – indeed a part of Enlightenment (and British) values, from Voltaire to Bertrand Russell. We should also be free to criticise Sharia law, as we are free to criticise other laws.

Justin Welby

As Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby pointed out recently, there also needs to be a discussion about the doctrinal links between religion and extremism:

“This requires a move away from the argument that has become increasingly popular, which is to say that ISIS is nothing to do with Islam, or that Christian militia in the Central African Republic are nothing to do with Christianity, or Hindu nationalist persecution of Christians in South India is nothing to do with Hinduism.”

Extreme and draconian statements can be found in the Old Testament of the Bible as well as in the Qur’an. Believing that they are obeying the word of God, these texts have spurred violent religious extremists, as we are all sadly aware.

Nevertheless, many modern Christians, Jews and Muslims have accepted the power of state law over religious law. They obey the laws of their country. They do not kill homosexuals (Leviticus 20:13), or slay apostates (Deuteronomy 13:6-10), or stone to death a bride who is not a virgin (Deuteronomy 22:20-21), or rape non-Muslim women (Qur’an 23:1-6, 70:22-30), or make war on unbelievers (Qur’an 8:12, 9:5, 9:73, 9:123).

We must help this vital transition from regressive religious law, toward a recognition of modern secular law and democracy. But we do not do so by pretending it is not needed, or refusing to discuss it, or branding those that discuss it as “Islamophobic”.

Signs of hope

On a more positive note, the authors of the 2007 Policy Exchange Report argued for a change of approach. The government and others “should stop emphasising difference and engage with Muslims as citizens”.

Policies of “group rights or representation” for specific Islamic communities are likely to alienate other sections of the Muslim population further. These well-informed remarks went against much of the then-current local and national government policy.

The authors continued: “The exaggeration of Islamophobia does not make Muslims feel protected but instead reinforces feelings of victimisation and alienation.” They also called for “a broader intellectual debate in order to challenge the crude anti-Western, anti-British ideas that dominate cultural and intellectual life. This means allowing free speech and debate, even when it causes offence to some minority groups.”

We need to be honest. Extremist religions of all kinds can threaten liberal, democratic and Enlightenment values. Christianity in particular has been violently repressive and brutal. Some religious sects today are fanatical and intolerant.

These issues need to be openly discussed, in a civilised manner. They should not be swept under the carpet by those on the Regressive Left who act as if they do not understand the difference between race and religion, or would shut down critical discussion of a religion because it might be wrongly construed by others as an attack on a minority, or by other politicians of any stripe who are simply too scared to take the issue on.

In an immensely positive development, the “Muslim Reform Movement” was launched in 2015. In their inaugural statement they defended freedom of speech, gender equality, a secular state and the UN Declaration of Universal Human Rights. They noted explicitly that freedom of speech included the right to criticize Islam: “Ideas do not have rights. Human beings have rights.”

By contrast, the blanket and ill-defined leftist rhetoric of “Islamophobia” does not help those Muslims who are struggling to reform and modernise their religion. Instead, the more conservative leaders of Muslim communities protect their regressive and reactionary views behind its smokescreen. Modernising Muslims are thus impaired by an unwitting coalition of leftists and Muslim conservatives.

Responsibility lies on both sides. In a climate of open discussion, we all need to be vigilant against acts of hatred or violence against Muslims and other minorities.

Initiatives to preserve liberal values in a multi-faith and multi-ethnic world should be welcomed. In addition, the Left needs to re-establish its links with the Enlightenment and its project to separate church from state. Within any society, freedom of worship should be protected, as well as the freedom to criticise religion.

Inward-looking, unreforming, dogmatic religion is a major barrier to assimilation. The Left needs to learn that lesson, and to encourage open discussion of the issues involved.

6 December 2016

Edited 7th and 10th December 2016, with thanks to Andrew Ross. Further edit, 23 January 2017.

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

References

Accord Coalition (2016) ‘Public overwhelmingly opposes religious discrimination in faith school admissions’, Accord, 2 November. http://accordcoalition.org.uk/2016/11/02/public-overwhelmingly-opposes-religious-discrimination-in-faith-school-admissions/

Asthana, Anushka and Nazia Parveen (2016) ‘Call for action to tackle growing ethnic segregation across UK’, The Gaurdian, 1 November. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/nov/01/call-for-action-to-tackle-growing-ethnic-segregation-across-uk

Asthana, Anushka and Peter Walker (2016) ‘Casey review raises alarm over social integration in the UK’, The Guardian, 5 December. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/04/social-integration-louise-casey-uk-report-condemns-failings

BBC News (2001) ‘MP calls for English tests for immigrants’, 17 July. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/1436867.stm

Bell, David (2005) ‘Full Text of David Bell’s Speech’, The Guardian, 17 January. http://www.theguardian.com/education/2005/jan/17/faithschools.schools

Board of Deputies of British Jews (2016) ‘Board of Deputies statement on meeting with Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn’, 9 February. https://www.bod.org.uk/board-of-deputies-statement-on-meeting-with-leader-of-the-opposition-jeremy-corbyn/

Butt, Hassan (2007) ‘My plea to fellow Muslims: You must renounce terror’, The Observer, 1 July. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/jul/01/comment.religion1

Casey, Louise (2016) ‘The tough questions on social integration are being ducked’, The Observer, 4 December. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/dec/04/tough-questions-social-integration-laws-values-every-person-britain

Cohen, Nick (2007) What’s Left? How the Left Lost its Way (London and New York: Harper).

Department of Education (2014) Promoting Fundamental British Values as Part of SMSC in Schools (London: Department of Education). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380595/SMSC_Guidance_Maintained_Schools.pdf

Department for Communities and Local Government (2016) The Casey Review: A review into opportunity and integration (London: Department for Communities and Local Government). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/574565/The_Casey_Review.pdf

Dobson, Roger (2014) ‘British Muslims face Worst Job Discrimination of any Minority Group, According to Research’, The Independent, 30 November. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/british-muslims-face-worst-job-discrimination-of-any-minority-group-9893211.html

Gillard, Derek (2007) Never Mind the Evidence: Blair’s Obsession with Faith Schools www.educationengland.org.uk/articles/26blairfaith.html

Greer, Germaine (1999) The Whole Woman (New York: Doubleday).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Husain, Ed (2007) The Islamist: Why I Joined Radical Islam in Britain, What I Saw Inside, and Why I Left (London Allan Lane).

Hussain, Dilly (2015) ‘How “British Values” are used as a Smoke Screen for Anti-Muslim Government Policies’, Stop the War Coalition, 15 June. Formerly http://www.stopwar.org.uk/news/how-british-values-are-used-as-a-smokescreen-for-anti-muslim-government-policies. Now unavailable.

Kinnock, Stephen (2016) ‘How to build an inclusive and patriotic view of Britishness’, Labour List, 2 December. https://labourlist.org/2016/12/kinnock-how-to-build-an-inclusive-patriotic-and-confident-view-of-britishness/

Malik, Kenan (2005) ‘The Islamophobia Myth’, Prospect, February. http://www.kenanmalik.com/essays/prospect_islamophobia.html

Mirza, Munira, Senthilkumaran, Abi and Ja’far, Zein (2007) Living apart Together: British Muslims and the Paradox of Multiculturalism (London: Policy Exchange), https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/living-apart-together-british-muslims-and-the-paradox-of-multiculturalism

Mortimer, Caroline (2016) ‘Justin Welby: It’s time to stop saying Isis has ‘nothing to do with Islam’”, The Independent, 19 November. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/isis-nothing-to-do-with-islam-justin-welby-archbishop-canterbury-religion-a7427096.html

National Secular Society (2015c) ‘Muslim Reform Movement Embraces Secularism and Universal Human Rights’, National Secular Society, 8 December. http://www.secularism.org.uk/news/2015/12/muslim-reform-movement-embraces-secularism-and-universal-human-rights

Portes, Jonathan (2012) ‘Inching towards integration?, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, 5 March. http://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/inching-towards-integration#.WEglE01vicx

Sides, John (2015) ‘New research shows that French Muslims experience extraordinary discrimination in the job market’, The Washington Post, 23 November. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/11/23/new-research-shows-that-french-muslims-experience-extraordinary-discrimination-in-the-job-market/

Toynbee, Polly (2004) ‘We Must be Free to Criticise without Being Called Racist’, The Guardian, 18 August. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/aug/18/religion.politics

Travis, Alan (2016) ‘Mass EU migration into Britain is actually good news for UK economy’, The Guardian, 18 February. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/feb/18/mass-eu-migration-into-britain-is-actually-good-news-for-uk-economy

White, Michael (2015) ‘Trevor Phillips says the Unsayable about Race and Multiculturalism’, The Guardian, 16 March 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/mar/16/trevor-phillips-race-multiculturalism-blog

Posted in Assimilation, Christianity, Democracy, Donald Trump, Immigration, Islam, Judaism, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Populism, Religion, Right politics

September 16th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

There are several different kinds of populism, emanating from both the left and right. But they have in common a view that some powerful minority group are clearly to blame for the ills suffered by a majority. As Julian Baggini put it, in his excellent article on Corbyn’s populism:

‘Populism is … a way of doing politics that has three key features. First, it has a disdain for elites and experts of all kinds, especially political ones. Second, it supposes that the purpose of politics is simply to put into action the will of the people, who are seen as homogenous and united in their goals. Third, it proposes straightforward, simple solutions to what are in fact complex problems.’

Rather than enter into a discussion over political problems and details, populists accuse those who fail to support them as collaborators of the exploiting elite. They believe that the elite is the main obstacle to progress, and solutions will appear once the elite is removed. They are suspicious of experts and dissenters. They are typically vague about their own objectives: their primary aim is to unite the bulk of the population behind a leader, against the elite.

The Great Crash of 2008 undermined confidence in existing elites. For this and other reasons, populism is now on the rise, in both Europe and the USA.

Populism on the Right

The campaign by UKIP to quit the European Union was populism incarnate. Its leader, Nigel Farage, complained frequently that the elites have gained too much power over hard-working ordinary people. Furthermore, elites at the national level had allegedly handed over power to unaccountable rulers in Europe, who have allowed mass immigration and robbed the UK of its sovereignty.

Because of his focus on a nationalist solution, and his identification of foreigners as a primary problem, Farage is an example of a right populist. By championing ‘ordinary British people’ against the establishment, and relying more on sentiment than on reasoned argument or expert advice, he is populist to the core.

After his success in the Brexit referendum, Farage flew across the Atlantic to show his support for Donald Trump. At his August 2016 speech at a Donald Trump rally in Mississippi, Farage celebrated that Britain ‘chose not to be ruled by unelected old men in Brussels’. He drew parallels between the US and Britain, saying ordinary people everywhere had been ‘let down by government’. He was greeted by rapturous applause.

After his success in the Brexit referendum, Farage flew across the Atlantic to show his support for Donald Trump. At his August 2016 speech at a Donald Trump rally in Mississippi, Farage celebrated that Britain ‘chose not to be ruled by unelected old men in Brussels’. He drew parallels between the US and Britain, saying ordinary people everywhere had been ‘let down by government’. He was greeted by rapturous applause.

Trump’s rhetoric has much in common with that of Farage. Both blame immigrants for the problems in the country. Trump adds his rabid hostility to Muslims.

Corbynism as Left Populism

There are important differences between populists on the left and right. Left populists place less emphasis on the role of immigrants or foreigners: they are more inclusionary. Left populists also tend to favour greater state involvement in the economy. But elements of right populism can find their way into left movements, and vice versa.

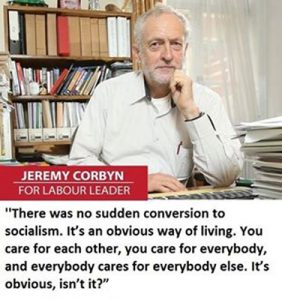

Jeremy Corbyn is very different from Nigel Farage and Donald Trump. Corbyn is neither a racist nor a misogynist (although he has shared political platforms with homophobes and anti-Semites). But Corbynism as a movement has strong populist features.

Jeremy Corbyn is very different from Nigel Farage and Donald Trump. Corbyn is neither a racist nor a misogynist (although he has shared political platforms with homophobes and anti-Semites). But Corbynism as a movement has strong populist features.

Other prominent examples of left populist movements include Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain and the ‘socialist’ regime established by the late President Hugo Chávez in Venezuela.

Labour has always been more pragmatic than ideological. Although Corbyn has some Marxist theoreticians close to him, including within his Momentum Praetorian Guard, he has relied much more on populist sentiment rather than Marxist theory.

The recent growth of left populism has been triggered by the crisis within social democracy, the disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003, increasing economic inequality within leading economies, unaffordable housing, cuts in the welfare state and high rates of unemployment, especially among the young.

Corbynism vaguely promotes ‘socialism’, but there is no apparent agreement on what this means. There is a general suspicion of private enterprise, as well as a justified concern about the excessive power of some large corporations. When difficulties appear, public ownership is typically seen as the simple and obvious cure.

Like all populists, Corbyn rails against the elite. For him it is the rich minority and the large corporations. Like Farage, he identifies an elite that is bolstered by powerful friends abroad. But for Corbyn the most important foreign allies of the despised British elite are in Washington DC. With its anti-West foreign policy, Corbynism is Marxism-Leninism in populist clothing.

Corbynism Undermines Parliamentary Democracy

To public ownership is added the populist Corbynista slogans of ‘democratic control’ or ‘democratic management’ of enterprises. Without any detailed explanation of how this would work, it nevertheless reassures the left-populist followers that they, and not the elite, will somehow be in control. This left-populist slogan of ‘democratic control’ is seen as the obvious and straightforward way to ‘put into action the will of the people’.

Some extension of worker and community participation is desirable. But it cannot be a substitute for managerial discretion and leadership. Corbyn’s ultra-democracy is infeasible. When it threatens parliamentary democracy it is dangerous.

The Corbynistas want to shift power away from Parliament. They want MPs to follow ‘the will of the people’, which means, in practice, the implementation in Parliament of the resolutions of their local constituency parties. Inadequate heed is taken of the diverse views and interests of the electorate, and the need for expert deliberation and debate to make policy feasible and effective.

Instead of careful, empirically-grounded debate among diverse viewpoints, aimed at developing viable policies to deal with complex economic and political problems, Corbynistas are suspicious of dissent from their official line.

Any defence of markets or private ownership is worrying for them. It challenges their ‘obvious’, ‘democratic’ and simplistic solutions, and therefore must be opposed. Such dissent is branded ‘Blairite’ or ‘red Tory’ or ‘neoliberal’.

Instead of pluralism and extended debate, Corbynism treats the party resolution as the correct line, which all are instructed to follow. There is little appreciation of the complexity of modern politico-economic systems, and the consequent fallibility of all decision making.

Parliamentary institutions have evolved to deal with real-world complexities. They provide some mechanisms to challenge and scrutinise legislation. By moving from representative to delegate democracy, Corbynism would corrode the basic institutions of parliamentary democracy.

Any leader of any political party committed to working through parliament would resign when 80 per cent of his or her parliamentary representatives passed a vote of no confidence in his or her leadership. When this happened, Corbyn did not resign: his primary focus is not on parliament but on the populist ‘mass movement’ outside.

Totalitarian Dangers of Populism – The Example of Venezuela

The record of both left and right populism in power is abysmal. There is an important example of left populism in power, and it is close to Corbyn’s heart.

He has always had a romantic soft spot for Latin American revolutionaries. He wrote in 2011: ‘What the Cubans and … Che Guevara were preaching in the 1960s has an even greater resonance today’. This suggests that armed insurrection is appropriate, even in those Latin American countries that have become democracies.

Jeremy Corbyn and Hugo Chávez

In 1998, the Marxist politician Hugo Chávez was elected as President of Venezuela. Using the high oil revenues during 1999-2007, his government expanded access to food, housing, healthcare, and education, especially for the poor and the indigenous minorities.

Chávez nationalized key industries and created participatory Communal Councils. His ‘Chavista’ populism emphasised the ‘will of the people’, against the rich elite and their perceived allies in the United States.

Chávez created new ‘democratic’ institutions at the base to bolster his power. In 1999, the new Constitutional Assembly, filled with elected supporters of Chávez, drafted a new constitution that made censorship easier and granted the executive branch of government more power. The Constitutional Assembly extended the presidential term. It abolished the two houses of Congress. It also granted Chávez the power to legislate on citizen rights, to promote military officers and to oversee economic and financial matters.

In 2002 Chávez was briefly deposed in a coup, which may have had support from foreign agencies such as the CIA. The hostility of the US government to his regime was no secret. But Chávez was restored to power by the army and popular mobilisations.

Chávez seized control of the courts and the electoral authority, and suppressed much of the opposition media. He removed political checks and balances, seeing them as obstacles to his socialist revolution.

Hugo Chávez

Accordingly, the device of populist democracy was used to push the country in the direction of dictatorship. The high pre-Crash oil revenues were used to address some basic needs and to buy the support of the people. These supporters were then persuaded to approve increases in presidential powers, to protect the ‘socialist revolution’ against its enemies.

Chávez failed to diversify the economy and reduce its reliance on oil. He antagonised private investors. The economy was not robust enough to withstand the post-2008 oil price collapse. His government had become one of the most corrupt in the world. Serious shortages of food and medicine emerged. Chávez died of cancer in 2013 and was replaced as President by Nicolás Maduro.

But Corbyn’s enthusiasm for the regime was undiminished. As late as 2015, when Venezuela was in ever-deepening crisis, he remarked:

‘we celebrate, and it is a cause for celebration, the achievements of Venezuela, in jobs, in housing, in health, in education, but above all its role in the whole world … we recognise what they have achieved.’

Food Shortages in Venezuela

These gave him powers to intervene more heavily in companies and in the currency markets. Arbitrary detentions of dissidents became more common.

In July 2016 he used his executive powers to decree that citizens could be forced to work in the country’s fields for 60-day periods, which may be extended ‘if circumstances merit.’

Starvation became rife. In August 2016 a gang of hungry Venezuelans broke into a zoo and butchered a horse for its meat.

Populism in general, and the left populisms of Chávez, Maduro and Corbyn in particular, are profound threats to any enduring and viable democracy. Using Chávez as a prime example. Kurt Weyland wrote:

‘Determined and politically compelled to boost their personal predominance, populist leaders strive to weaken constitutional checks and balances and to subordinate independent agencies to their will. They undermine institutional protections against the abuse of power and seek political hegemony. Correspondingly, populist leaders treat opponents not as adversaries in a fair and equal competition, but as profound threats. Branding rivals “enemies of the people,” they seek all means to defeat and marginalize them. Turning politics into a struggle of “us against them,” populists undermine pluralism and bend or trample institutional safeguards.’

“There’s no food”

The tragic example of Venezuela is a warning to us all. Like Corbyn, Chávez started with a fairly modest economic programme, closer to social democracy than Marxist orthodoxy. But to bolster his power, Chávez extended state control. Maduro further undermined freedom of speech and put opponents in jail.

Because of a populist mistrust of liberal, pluralist institutions, Venezuela is lurching toward despotism. Currently it retains some semblance of democracy, but press freedom is limited and critical journalists are jailed. Since 2004, ‘defamation’ of the government, including ‘disrespect for the authorities’, has been a criminal offence.

Supporters of Chávez and Maduro blame the hostility of the US for Venezuela’s distress, just as it was blamed for economic problems in Cuba after its 1959 revolution. US belligerence made things worse. But the major cause of economic stagnation in both places is the hobbling of the private sector, and the unchecked concentration of excessive political, legal and economic power in the hands of the overbearing state.

Populism must be Defeated

Although it is unlikely that either UKIP or Corbyn’s Labour will ever win power, they can do serious damage to public debate and the functioning of a parliamentary democracy. In particular, by neutering Labour as a parliamentary force, the UK is deprived of an effective opposition to the Tory government.

Consider the example of the EU referendum in June 2016. After the result, Corbyn took it for granted that Britain should leave the EU and immediately trigger Brexit, irrespective of the outcome of Britain’s negotiations on the terms of leaving. Like his fellow-populist Farage, Corbyn accepted that ‘the people had spoken’. For him, the expression of popular will was the end of the matter.

Consider the example of the EU referendum in June 2016. After the result, Corbyn took it for granted that Britain should leave the EU and immediately trigger Brexit, irrespective of the outcome of Britain’s negotiations on the terms of leaving. Like his fellow-populist Farage, Corbyn accepted that ‘the people had spoken’. For him, the expression of popular will was the end of the matter.

After the June 2016 vote to leave the EU, Britain is probably in its worse political crisis since the Second World War. It faces years of political and economic uncertainty, with no obvious resolution. In these circumstances, popular frustration and deprivation can feed populism. Left populism has its own dangers, and we know from history that left populists can shift to the right. In turn, right populism can feed fascism.

All populisms, including Corbynism, pose a serious threat to representative democracy. As Baggini put it:

‘Our tradition of representative democracy rests on a rejection of all three pillars of populism. It accepts that a well-run society needs specialists and full-time politicians whose judgments often carry more weight than those of voters who put them into power. It accepts that the “will of the people” is diverse and contradictory, and that the job of politics is to balance competing demands, not simply to obey them. It follows that there are few, if any, easy solutions and that anyone who promises them is a charlatan. Making the case for representative democracy therefore means telling the electorate it doesn’t always know best, a truism that populism has turned into an elitist heresy.’

Populists do not understand that political checks and balances, safeguarded by countervailing politico-economic power, are necessary to help protect democracy and liberty. With confidence in their ‘obvious’ solutions to complex problems, they treat criticism with disdain and close down reasonable discussion. All must ‘unite behind the leader’ who is revered for saving the masses from the enemy elite.

For these reasons Corbynism must be treated as a dangerous ideological threat to a liberal democracy, and not as an infantile, reversible outburst of ultra-leftism.

No-one has a feasible strategy to turn Labour back to its previous form. History offers no clear example of the internal undoing of populist fanaticism. It has always been defeated from outside. Labour is now irretrievable: there is no way of reversing the populist entrenchment within.

Corbyn’s Labour is a danger for the British political system as the Tories are for its economy and for its social fabric. Corbynism is a threat to liberal, pluralist democracy.

We need to build a progressive opposition to both Toryism and Corbynism. We need to defend liberal, pluralist democracy from the populisms of left and right. Building an alternative will take a generation, but we must start now.

16 September 2016

Minor edits: 17,18, 22 September 2016

Major edit: 18 June 2017

Bibliography

Bagehot (2016) ‘Why a “True Labour” splinter party could succeed where the SDP failed’, The Economist, 12 April. http://www.economist.com/blogs/bagehot/2016/08/labour-pains.

Baggini, Julian (2016) ‘Jeremy Corbyn is a great populist. But that’s no good for our democracy’, The Guardian, 30 July. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jul/25/jeremy-corbyn-populist-democracy-mps.

Borger, Julian (2016) ‘Venezuela’s worsening economic crisis’, The Guardian, 22 June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/22/venezuela-economic-crisis-guardian-briefing

Canning, Paul (2016) ‘Venezuela: The Left’s giant forgetting’. http://paulocanning.blogspot.co.uk/2016/09/venezuela-lefts-giant-forgetting.html

Corbyn, Jeremy (2011) ‘Foreword, to John A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study’, facsimile reprint of 1902 edition (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Cunliffe, Rachel (2016) ‘Corbyn looks the other way as Venezuela self-destructs’, 18 January, http://capx.co/corbyn-looks-the-other-way-as-venezuela-self-destructs/.

Lawson, Neal (2016) ‘Social democracy without social democrats: how can the left recover?’ New Statesman. 12 May. http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2016/05/social-democracy-without-social-democrats-how-can-left-recover.

Telesur (2015) ‘British MP Jeremy Corbyn speaks out for Venezuela’, 6 June. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/British-MP-Jeremy-Corbyn-Speaks-Out-For-Venezuela-20150605-0033.html.

Weyland, Kurt (2013) ‘The threat from the populist left’, Journal of Democracy, 24(3), pp. 18-32.

Wikipedia (2016) ‘Populism’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populism.

Posted in Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Populism, Socialism, Uncategorized, Venezuela

August 16th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

“This, from the always measured g. m. hodgson, shows Labour’s existential crisis in horrifying detail” – Susan Wilde

“The revolutionary road: excellent sober distillation of Marxism/Leninism/Trotskyism/socialism; rights v insurrection” – Rich Greenhill

“A very good summary of Labour and Trotskyism” – Gerry Hassan

“Another fantastic article!” – Lily Jayne Summers

John McDonnell, the Labour Shadow Chancellor, is an admirer of Trotsky. Corbyn once called upon the USSR to rehabilitate the Russian revolutionary.2

Trotskyists are socialists who believe in the common ownership of the means of production. This goal was stated in Labour’s Clause Four from 1918 to 1995, so why shouldn’t Trotskyists be allowed to join Labour?

Trotskyists are socialists who believe in the common ownership of the means of production. This goal was stated in Labour’s Clause Four from 1918 to 1995, so why shouldn’t Trotskyists be allowed to join Labour?

Trotskyists differ from the devotees of Mao Zedong or Joseph Stalin. Trotskyists do not describe the murderous regimes of Mao’s China and the USSR as socialist. They promote themselves as anti-totalitarian, and they might seem much more democratic than other Marxists.

So why shouldn’t Trotskyists be allowed to join Labour?

The Parliamentary versus the Revolutionary Road

There is a prominent negative answer to this question. It raises profound differences of strategy. As Neil Kinnock (who did the party a great service by kicking out Militant in 1985) said in a speech to the Parliamentary Labour Party in July 2016:

‘In 1918 in the shadow of the Russian revolution [Labour members decided] … that they would not pursue the revolutionary road – it was a real choice in those days. They would pursue the parliamentary road to socialism.’

According to this view, Labour members and revolutionary Marxists share the same aim – socialism – but they differ on the method of getting there. Labour follows the parliamentary road; Marxists choose the revolutionary road.

Robert Owen

There are big problems with a part of this argument. Socialism was defined by Robert Owen and Karl Marx in terms of common ownership of the means of production and ‘the abolition of private property’.

But at least in practice since 1945, Labour has been less and less devoted to this goal. Finally, the goal of ‘common ownership’ was removed from Clause Four of the Labour Party Constitution in 1995.

Labour now says that it is a ‘democratic socialist’ party but defines this not in terms of common ownership. Instead there is a goal of social solidarity, believing ‘that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone’, and in a society ‘in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few’.

Arguably, such a goal might be achievable in a reformed capitalism. But Trotskyists, like all Marxists, are emphatically against capitalism.

What Trotskyists and the post-1995 Labour Party Constitution mean by ‘socialism’ are very different. The divergences between Labour and Trotskyists concern different ends, as well as different means.

But Corbyn’s election as Leader by over 59 per cent of the membership in 2015 shows that the traditional definition and goal of socialism in the Labour Party is far from dead and buried. Under Corbyn’s leadership, Labour could return to its pre-1995 goals.

Tony Blair

Ironically, by getting rid of the traditional ‘common ownership’ version of socialism in 1995, but retaining the word ‘socialism’ in an attempt to invest it with a different meaning, Tony Blair provided legitimacy for any later attempt by classical socialists – including currently by Trotskyists and Corbynistas – to restore Labour to its original colours.

Within Labour today, because of this legacy, everyone from Trotskyists and Corbynistas at one extreme, through Owen Smith, Neil Kinnock and then on to Tony Blair at the other extreme, is obliged to call themselves a ‘socialist’. But there are massive silences and huge disagreements on its meaning.

Labour becomes less capable of discussing fundamental differences of goal, but clings onto the illusion of the fundamental goodness of something called ‘socialism’. Labour’s problem of entryism will never go away while the s-word continues to cast its spell. The word itself is an invitation for those who propose the common ownership of anything to join.

The Totalitarian Politics of Class Struggle

There are other fundamental problems with Marxism in general, and Trotskyism in particular. First, Marxism rejects the supreme values of the Enlightenment.

For example, Frederick Engels in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, saw these Enlightenment values as ‘nothing more than the idealized kingdom of the bourgeoisie’ with its ‘bourgeois justice’, its ‘bourgeois equality before the law’ and ‘bourgeois property … proclaimed as one of the essential rights of man’.

Marxists do not see the French Revolutionary principles of liberty, equality and fraternity as a potential achievement for all, but the rhetoric of the rising capitalist class in the class struggle against the old feudal order.

Marxists do not see the French Revolutionary principles of liberty, equality and fraternity as a potential achievement for all, but the rhetoric of the rising capitalist class in the class struggle against the old feudal order.

After playing their progressive historic role, Enlightenment ideas are seen as ‘bourgeois’ ideology, which now serves to repress the working class.

Marx saw socialism as the class destiny of the proletariat, which by overthrowing capitalism would emancipate humankind from inequality and exploitation. Socialism was not validated by an appeal to justice or rights. Instead it was grounded on ‘material’ and ‘economic’ developments within capitalism that were leading to growing internal crises and the rise of the proletariat.

Marx rejected all appeals to rights or justice. He bypassed the issues of morality and justice by focusing on the real social forces allegedly leading to socialism. But neither the driving forces of history nor the supposed destiny of a social class make this socialist future just, or morally right.

Karl Marx

By shelving the discourse on rights, in favour of the scientifically-clothed rhetoric of proletarian destiny, all versions of Marxism – including Trotskyism – are on the slippery slope toward totalitarianism.

When rights are no longer universal, and no-one has the protection of an independent legal system, the any action that is deemed ‘counter-revolutionary’ or ‘against the interests of the working class’ gives the accused no effective defence. The prosecutors monopolise the interpretation of guilt. Arbitrary punishment can follow.

The rights of critics and dissenters have to be protected, by their formal recognition and the autonomy of the judiciary. Unless this is done, any criticism can be crushed.

Trotsky was wrong: the roots of totalitarianism do not lie principally in the personalities of brutal, power-hungry individuals such as Stalin, but in Marxism itself. As Leszek Kolakowski suggested:

‘Marx’s anticipation of perfect unity of mankind and his mythology of the historically privileged proletarian consciousness … were responsible for his theory being eventually turned into an ideology of the totalitarian movement: not because he conceived of it in such terms, but because its basic values could hardly be materialized otherwise.’

Violence versus Parliament and Law

Laws get in the way of revolutionary struggle. Hence, along with their dilution of the notion of rights, Lenin proposed that all laws should be abolished.

Writing in 1918, Lenin described the desired ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ as ‘rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws. The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws.’ Trotsky supported Lenin in this and most other respects.

Writing in 1918, Lenin described the desired ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ as ‘rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws. The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws.’ Trotsky supported Lenin in this and most other respects.

Consequently, a fundamental problem with Marxism is its failure to support the universality of human rights. Human rights apply to all, as in the majestic 1948 United Nations Declaration of Universal Human Rights.

Instead, Marxists see social advancement as a matter of ‘class struggle’ where one class must seize power and remove rights from another class. Lenin and Trotsky went one step further: they argued that this struggle for proletarian power must override the rule of law.

The Second Congress of the Communist International took place in Russia in 1920. Under the leadership of Lenin, one of its resolutions mentioned ‘bourgeois parliaments’ and declared:

‘The task of the proletariat consists in breaking up the bourgeois state machine, destroying it, and with it the parliamentary institutions, be they republican or constitutional monarchy.’

Throughout his life, Trotsky defended the decisions of the first four congresses of the Communist International, which took place when Lenin was alive and before Stalin seized power.

Throughout his life, Trotsky defended the decisions of the first four congresses of the Communist International, which took place when Lenin was alive and before Stalin seized power.

Trotsky added his own idea of ‘permanent revolution’, involving civil war, even in a parliamentary democracy:

‘Socialist construction is conceivable only on the foundation of the class struggle, on a national and international scale. This struggle … must inevitably lead to explosions, that is, internally to civil wars and externally to revolutionary wars. Therein lies the permanent character of the socialist revolution as such, regardless of whether it is a backward country … or an old capitalist country which already has behind it a long epoch of democracy and parliamentarism.’

Conclusion: Hands Tied Behind their Backs

Those in Labour wanting to fight the battle against entryism have two hands tied behind their backs.

First, by hanging on to the word ‘socialism’, after abandoning its original meaning, it is difficult to exclude those who are more genuinely socialist in the classical sense of common ownership. Labour’s obligatory (but now shallow) rhetoric of ‘socialism’ is a green light for socialist entryists of all kinds.

First, by hanging on to the word ‘socialism’, after abandoning its original meaning, it is difficult to exclude those who are more genuinely socialist in the classical sense of common ownership. Labour’s obligatory (but now shallow) rhetoric of ‘socialism’ is a green light for socialist entryists of all kinds.