August 10th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

‘This is a thundering good read’ – Peter Smith

‘The best article I’ve read for a while’ – Karen Bradley

‘Brilliant on why socialism isn’t “obvious”’ – Robbie Hudson

‘Very informative & sobering. Highly recommended’ – Jan Davies

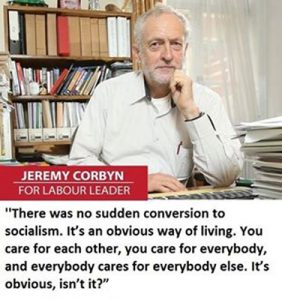

One thing in British politics is very obvious: Jeremy Corbyn and his followers are very keen on something they call socialism. But this word has migrated in meaning since it first appeared in English in 1827. So it is reasonable to ask what they mean by it.

I’ve tried. I got lots of vague answers.

I fully appreciate that the Mirror is an unsuitable forum for a detailed account of the workings of the future socialist utopia, but unfortunately I have little else to go on. Apart from some gestures in favour of nationalization, and some sentimentality for the pre-Blair version of Labour’s Clause Four, I can find no fuller account of what Corbyn’s ‘socialism’ means.

Yet we are told twice (in one short quote) that it is ‘obvious’.

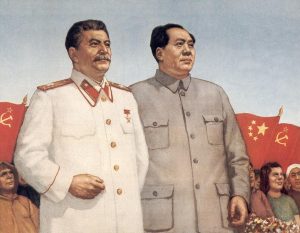

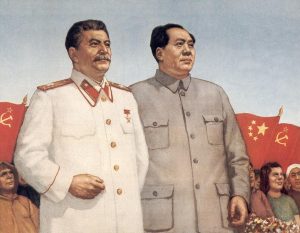

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

My comrades and I saw these deformations as unfortunate results of Stalinist bureaucracy plus Western hostility. We believed that a different, ‘democratic socialism’, was possible.

What persuaded me that socialism is not ‘obvious’ was a consideration of how such a system could work, in detail and in practice. How would production and distribution be organised? How would dispersed information concerning production and distribution be gathered and processed? How would resources be allocated? Who would decide? How would trillions of dispersed decisions be somehow processed by democratic committees? How would less-devoted workers be incentivized or persuaded to work harder or with greater attention to detail? What incentives would exist to encourage innovation and change, especially when everything had to be referred to some democratic council? And so on.

Once you begin to ask these difficult questions, socialism becomes much less ‘obvious’.

Numbers and incentives

Some version of socialism might work on a small scale. Cooperation can work in small groups, based on close, inter-personal interactions. Humans have co-operated in this way, in families and tribal units, for many thousands of years.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Their small size allows participants to monitor each other, to ensure that necessary tasks are carried out and that the interests of the community are served.

Enforcement mechanisms range from praise to punishment. Within these relatively small and cohesive groups, trust and targeted sanctions are mechanisms for encouraging cooperation, reciprocity and compliance with social rules.

But these mechanisms depend on a degree of familiarity with one another. Big problems emerge when we move from tribal to large-scale societies. These began to develop about twelve thousand years ago. Our natural and cultural dispositions to cooperate and to help one another had to be supplemented by other mechanisms.

In larger societies, face-to-face, trust-based mechanisms to sustain cooperation are relatively less effective. When we move from communities of a hundred or so, where it is possible for everyone to know everyone else, to communities of thousands or more, then interpersonal trust and reputation are much less successful with large-scale interactions, and they have to be supplement by other incentives and constraints.

The increase of scale can create incentive problems that can be overcome in smaller communities. Many socialist experiments involved collectivisation. But when thousands of people are brought together, and rewards are shared, then there is less incentive to make the extra effort, because the rewards from that additional work would be hugely diluted.

This problem was illustrated dramatically in China. After the Communist Revolution of 1949, agriculture was organized into large collective farms. Farmers had little incentive to improve productivity, other than by threats and bureaucratic bullying. Risky innovation was unwise. Productivity remained low and often there were shortages of food.

Mao Zedong died in 1976, opening up the possibility of reform. In 1978 some peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate.

After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty. China’s spectacular economic growth began when agriculture began to pass into the private control of the peasants after 1978.

|

This book by G. M. Hodgson elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

While interpersonal interactions can engender cooperation on a small scale, and they continue to do so in families and small communities, in large-scale societies other mechanisms and incentives are necessary. Economic history teaches us that modern dynamic economies depend on markets, competition and a large private sector, as well as an effective state.

Corbyn is right: it is very important that we care for one another. But in terms of practical input, we cannot care equally for everyone. We can care more readily for those close to us, who we know well: our family, our friends and our workmates. But extending our caring to society as a whole becomes more of a political and less of a personal project. We need caring governments, but the practical extension of caring from the personal to the political is neither obvious nor easy.

Corbyn is right: it is very important that we care for one another. But in terms of practical input, we cannot care equally for everyone. We can care more readily for those close to us, who we know well: our family, our friends and our workmates. But extending our caring to society as a whole becomes more of a political and less of a personal project. We need caring governments, but the practical extension of caring from the personal to the political is neither obvious nor easy.

The need for countervailing power

A simplistic response would be to suggest that we elect a government that is staffed by well-meaning individuals. But to different degrees, almost everyone is corruptible. Even the uncorrupt have their own biased agendas and priorities.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

Even if politicians are competent and well meaning – lots of them are – they still face the problems of dispersed knowledge and uncertainty in modern, large-scale, and highly complex economies.

Consequently, relatively little can be planned from the top. Solutions to real-world, nitty-gritty problems are rarely ‘obvious’. There is a need for both humility and experimentation. We need to try and see what works and learn from mistakes, rather that rushing headlong towards what seems obvious.

The survival of democracy depends on a dispersion of real economic and political power. A healthy, pluralist polity depends on a pluralist economy, with multiple centres of autonomous decision-making. This means a system of private enterprise, as well as a political system with checks, balances and power that can be held to account. The state can and must also play a vital role in the economy, but not to the extent that it smothers private enterprise and initiative.

There is a large and fascinating analytical literature on the problems involved in classical socialism, and I cite a few works on this below. There is not the space to go into it further here. These works are not all written by neoliberals. But intelligent neoliberals – despite their limitations – are often worth reading. Although there are disagreements on approach and detail, the general conclusion is that large-scale socialism cannot work effectively and democratically. This analytical conclusion is corroborated by the historical experience of stagnation in innovation in Soviet-style regimes.1

The ‘obvious’ roots of fanaticism and intolerance

The ‘obviousness’ of socialism empowers its supporters with enduring energy and even fanaticism. If socialism is ‘obvious’, how do we explain the failure of other intelligent people to get on board? If they are not stupid, then they must be acting out of personal malice or greed. They must have sold out their principles in some way. Or they are just plain nasty. When socialism is seen as ‘obvious’, its opponents are regarded as stupid or evil.

The perceived ‘obviousness’ of socialism fuels both fanaticism and intolerance. Because the solution to the problem is ‘obvious’, there can be no doubt. There is no need to experiment, to seek wise counsel, or to listen to critics. Those that deny the obvious are deluded, corrupted, or in the pay of those that gain from the existing system.

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

‘What is objectionable, what is dangerous about extremists is not that they are extreme, but that they are intolerant. The evil is not what they say about their cause, but what they say about their opponents.’

We have seen this elsewhere, in the brutal fanaticism of religious zealots, as well as in the murderous tragedies of twentieth-century socialism under Stalin and Mao. They all shared in common the absence of doubt, the certainty of redemption or victory, and the confidence in their own righteousness.

It is deeply saddening that the once-great British Labour Party has been taken over by people who think that their aims and long-term solutions are ‘obvious’. Once the zealots take over, there is no way back. The party is then trapped in a vicious circle.

A diminished vote in an election is a success because it is seen as a big vote for a purer socialism. When Labour lost the 1983 election on a socialist manifesto, with the lowest share of the vote since 1918, Tony Benn greeted the result as a triumph for socialist ideas.

Even small successes – such as winning elections to parish councils – feed frenzies of celebration. All acknowledged failures are blamed on others, such as the ‘mainstream media’ or the ‘traitors’ within.

Even small successes – such as winning elections to parish councils – feed frenzies of celebration. All acknowledged failures are blamed on others, such as the ‘mainstream media’ or the ‘traitors’ within.

With an ideology where no possible event can falsify the ‘obvious’, the doubters are purged. The wise give up. The fanatics win.2

Touting socialism as an ‘obvious’ solution empowers a fanaticism that can crush all traces of liberal tolerance, which is essential for democracy within any political party, as well as within the political system as a whole. Corbyn’s victory in the 2016 leadership election marks the point of no return for Labour. It is beyond the beginning of the end. Labour is now dying. Thoughtful radicals must go elsewhere.

10 August 2016

Minor edits – 11-13 August 2016

A version of this post was published in the i newspaper on 11 August.

More comments on this post:

‘A gloomy but sadly very acute and perceptive analysis’ – Helen Salmon

‘Definitely one of his best, and the best thing I’ve read all week’ – Tom Atkinson

‘Excellent article on the anti-democratic nature of seeing one’s views as “obvious”’ – Francis Hoar

‘Brilliant piece on why “obvious” socialism leads to intolerance (and doesn’t work either)’ – Colin Talbot

‘Thank you so much for your still small voice of reason: it is worth its weight in gold amid this chaos’ – Elizabeth Jones

End Notes

- A recent contribution of mine on the socialist calculation debate can be found here.

- After publication, Colin Williams kindly pointed out that the Russell quote that heads this post – although widely attributed to him and close to other similar quotes by Russell – cannot be found in this exact form in Russell’s works.

Bibliography

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1944) The Road to Serfdom (London: George Routledge).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Lavoie, Donald (1985) Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Mill, John Stuart (1859) On Liberty (London: John Parker & Son).

Nove, Alexander (1991) The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Steele, David Ramsay (1992) From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court).

Zhou, Kate Xiao (1996) How the Farmers Changed China (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Politics, Private enterprise, Socialism, Tony Benn

July 30th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Once upon a time, all socialists saw the ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’ as their primary aim. Many die-hards still do.

Others now focus instead on reducing inequalities of power, wealth and income. Some past or present contenders for leadership of the UK Labour Party, including Yvette Cooper and Owen Smith, have argued that the party’s aims in Clause Four of its constitution, should be rewritten to give greater emphasis to equality.

Smith has gone even further, to declare that Labour should focus on ‘equality of outcomes’ and not simply equality of opportunity. He proposed a wealth tax and an increase of the top rate of income tax to 50 per cent. Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership team claimed that they had already adopted these policies.

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership.

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership.

We also need to look at the basic drivers of inequality within capitalism. We must consider what can be done, within this system, and short of some mythical socialist future.

The practicalities of trying to reduce inequality within capitalism have to be addressed. If higher taxes are part of the solution, then somehow, in a democracy, people have to be persuaded to adopt them. Additional measures to help reduce inequality should be devised.

Furthermore, talk of ‘equality of outcomes’ is ill-advised. Are we really going to give everyone the same income and wealth, thus removing incentives for creativity and hard work? Is the communist utopia – ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his need’ – practical, or even desirable?

The aim should be to dramatically reduce inequality, not to eliminate it. Incentives for hard work and enterprise should be retained.

Shifting the focus from common ownership to the reduction of inequality is an important step forward. But the analysis of causes, and the design of policy, have to be much more sophisticated.

The problem of inequality

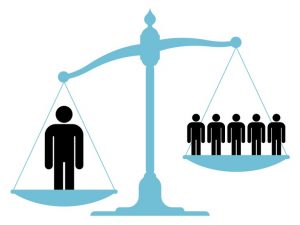

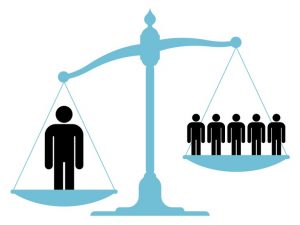

At least nominally, capitalism embodies and sustains an Enlightenment agenda of freedom and equality. Typically there is freedom to trade and equality under the law, meaning that most adults – rich or poor – are formally subject to the same legal rules. But with its inequalities of power and wealth, capitalism darkens this legal equivalence.

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett showed multiple deleterious effects of inequalities of income and wealth. Using data from twenty-three developed countries and from the separate states of the United States, they observed negative correlations between inequality, on the one hand, and physical health, mental health, education, child well-being, social mobility, trust and community life, on the other hand. They also found positive correlations between inequality and drug abuse, imprisonment, obesity, violence, and teenage pregnancies. They suggested that inequality creates adverse outcomes through psycho-social stresses generated through interactions in an unequal society.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

But first we must be clear about the drivers of inequality within the system. What are the mechanisms within capitalism that exacerbate inequalities of income or wealth?

Some inequality results from individual differences in talent or skill. But this cannot explain the huge gaps between rich and poor in many capitalist countries. Much of the inequality of wealth found within capitalist societies results from inequalities of inheritance. The process is cumulative: inequalities of wealth often lead to differences in education, economic power, and further inequalities in income.

Do markets create inequality?

To what extent can inequalities of income or wealth be attributed to the fundamental institutions of capitalism, rather than a residual landed aristocracy, or other surviving elites from the pre-capitalist past? A familiar mantra is that markets are the source of inequality under capitalism. Can markets be blamed for inequality?

In real-world markets different sellers or buyers vary hugely in their capacities to influence prices and other outcomes. When a seller has sufficient saleable assets to affect market prices, then strategic market behaviour is possible to drive out competitors.

Would more competition, with greater numbers of market participants, fix this problem? If markets per se are to be blamed for inequality, then it has to be shown that competitive markets also have this outcome. Unless we can demonstrate their culpability, blaming competitive markets for inequalities of success or failure might be like blaming the water for drowning a weak swimmer.

To demonstrate that competitive markets are a source of inequality we would have to start from an imagined world where there was initial equality in the distribution of income and wealth, and then show how markets led to inequality. I know of no such theoretical explanation.

Markets involve voluntary exchange, where both parties to an exchange expect benefits. One party to the exchange may benefit more than the other; but there is no reason to assume that individuals who benefit more, or benefit less (in one exchange) will generally do so. And if some traders become more powerful in the market than others, then its competitiveness is reduced.

The sources of inequality within capitalism

So if markets per se are not the root cause of inequality under capitalism, then what is? A clear answer to this question is vital if effective policies to counter inequality are to be developed. Capitalism builds on historically-inherited inequalities of class, ethnicity, and gender. By affording more opportunities for the generation of profits, it may also exaggerate differences due to location or ability. Partly through the operation of markets, it can also enhance positive feedbacks that further magnify these differences. But its core sources of inequality lie elsewhere.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral.

By contrast, capitalists may use their property to make profits, and as collateral to borrow money, invest and make still more money. Differences become cumulative, between those with and without collateralizable assets, and between different amounts of collateralizable wealth. Even when workers become home-owners with mortgages, the wealthier can still race ahead.

Unlike owned capital, free labour power cannot be used as collateral to obtain loans for investment. At least in this respect, capital and labour do not meet on a level playing field, this asymmetry is a major driver of inequality.

The foremost generator of inequality under capitalism is not markets but capital. This may sound Marxist, but it is not. I define capital differently from Marx and from most other economists and sociologists. My definition of capital corresponds to its enduring and commonplace business meaning. (Piketty’s definition is also similar to mine.) Capital is money, or the realizable money-value of collateralizable property. Unlike labour, capital can be used as collateral and the loan obtained can help generate further wealth.

Because workers are free to change jobs, employers have diminished incentives to invest in the skills of their workforce. Especially as capitalism becomes more knowledge-intensive, this can create an unskilled and low-paid underclass and further exacerbate inequality, unless compensatory measures are put in place. A socially-excluded underclass is observable in several developed capitalist countries.

Another source of inequality results from the inseparability of the worker from the work itself. By contrast, the owners of other factors of production are free to trade and seek other opportunities while their property makes money or yields other rewards. This puts workers at a disadvantage. Through positive feedbacks, even slight disadvantages can have cumulative effects.

None of these core drivers of inequality can be diminished by extending markets or increasing competition. These drivers are congenital to capitalism and its system of wage labour. If capitalism is to be retained, then the compensatory arrangements that are needed to counter inequality cannot simply be extensions of markets or private property rights.

These ineradicable asymmetries between labour and capital mean that ultra-individualist arguments against trade unions are misconceived. In a system that is biased against them, workers have a right to organize and defend their rights, even if it reduces competition in labour markets.

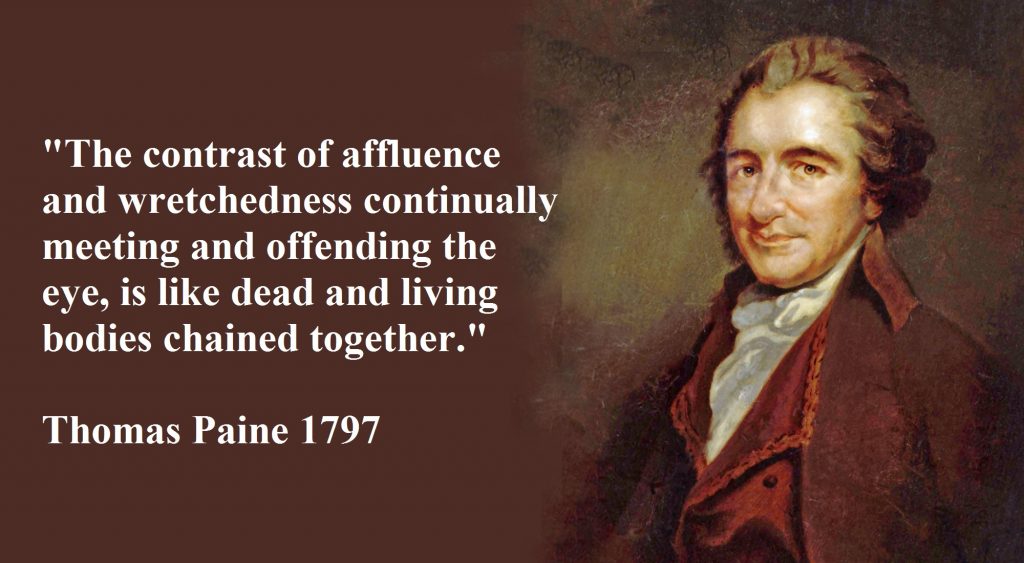

The relevance of Thomas Paine

Contrary to a widespread myth, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was a liberal rather than a socialist. There is no support for common ownership in his writings. Instead he support private enterprise and a market economy.

But over two hundred years ago, he set out arguments and methods for reducing inequality. Paine recognised that ownership of property was vital, to provide incentives for the generation of wealth and to provide a means for its fairer distribution.

Paine argued for an inheritance tax, but balanced this by a grant to each adult at reaching the age of maturity. In this way, wealth would be recycled from the dead to the young, providing greater equality of opportunity across the board. Paine also advocated welfare provision and a guaranteed pension for those over 50.

Much of the wealth in Paine’s time was in land. Land and buildings are immobile, and can be readily assessed and taxed. But capital is fleet-footed and covert: it can be easily moved around the world or hidden in foreign accounts. Land ownership is still highly concentrated in a few hands, along with much additional wealth.

Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada.

Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada.

Although there are important variations, other developed countries show similar patterns of inequality within this range. The problem is extreme in the USA. Lower levels of inequality elsewhere are far from satisfactory, but they indicate what might be politically feasible for the currently more unequal countries.

Spreading property

Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott took up Paine’s agenda in their proposal for a ‘stakeholder society.’ They argued that ‘property is so important to the free development of individual personality that everybody ought to have some’. They echoed Francis Bacon: ‘Wealth is like muck. It is not good but if it be spread.’

To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes.

To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes.

Significantly, the Right has promoted home ownership, while it has often been rebutted by the Left. This resistance comes from the Left’s old-fashioned, over-extended collectivism. By contrast, it is important for the Left to champion home ownership within an egalitarian and redistributive political programme.

When Margaret Thatcher introduced the ‘right to buy’ for tenants in social housing in 1980, Labour responded in its 1983 General Election Manifesto with a pledge to reverse these sales. But by 1985 Labour had abandoned this position.

Recycling wealth across generations

Ackerman and Alstott stressed progressive taxes on wealth rather than on income. Echoing Paine, they proposed a large cash grant to all citizens when they reach the age of majority, around the benchmark cost of taking a bachelor’s degree at private university in the United States. This grant would be repaid into the national treasury at death. To further advance redistribution, they argued for the gradual implementation of an annual wealth tax of two percent on a person’s net worth above a threshold of $80,000. Like Paine, they argued that every citizen has the right to share in the wealth accumulated by preceding generations. A redistribution of wealth, they proposed, would bolster the sense of community and common citizenship.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

People will be more ready to accept wealth taxation if they have earlier benefitted from a large cash grant in their youth. Wealth would by recycled to younger generations rather than syphoned away. The more fortunate or successful can be persuaded to give up some of their advantages if they see the benefits for society as a whole.

A related proposal, also redolent of Paine, was launched by the British Labour Government in 2005. It introduced a Child Trust Fund with the aim of ensuring every child has savings at the age of 18, giving every child a financial boost that they could use for the purposes of education or enterprise. Children received an initial £250 subscription from the government. Family and friends could top up these trust funds. The child would attain control of the fund at age 18. Withdrawals could then be made but be exempt from taxation. A weakness of this particular scheme was its timidity. A greater government subscription would have been more redistributive and egalitarian in its consequences. Child Trust Funds were opposed by the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, and abolished after they came to power in a coalition in 2010.

Extending education and share ownership

In the economy, there are many ways of spreading power and influence more broadly. The idea of extending employee shareholding is growing in popularity. This is a flexible strategy for extending ownership of revenue-producing assets in society. In the USA alone, over ten thousand enterprises, employing over ten million workers, are part of employee-ownership, stock bonus, or profit-sharing schemes. Employee ownership can increase incentives, personal identification with the enterprise, and job satisfaction for workers. The evidence suggests that when employee-ownership schemes and some employee participation in decision-making are combined, greater increases in profitability and productivity can be obtained.

As modern capitalist economies become more knowledge-intensive, access to education to develop skills becomes all the more important. Those deprived of such education suffer a degree of social exclusion, and, unless it is addressed, this problem is likely to get worse. Widespread skill-development policies are needed, alongside integrated measures to deal with job displacement and unemployment.

A universal basic income

The need for ongoing education is one argument for a basic income guarantee. Such a basic income would be paid to everyone out of state funds, irrespective of other income or wealth, and whether the individual is working or not. It is justified on the grounds that individuals require a minimum income to function as free and choosing agents. The basic means of survival are necessary to make use of our liberty, to have some autonomy, to function as effective citizens, to develop ethically, and to participate in civil society. These are conditions of adequate and educated inclusion in the market world of choice and trade.

A basic income would also reward otherwise unpaid work in care for the sick or elderly, which is often performed within families. A basic income would also encourage new entrepreneurs and creative artists. There would also be a huge saving in administration costs of often complex social security and welfare schemes. The level of the basic income does not have to be high. It can be set as a basic minimum for survival, thus retaining strong incentives for most people to seek additional sources of income.

Some forms of unconditional basic income have been pledged or introduced in several countries, including Brazil and Finland. Several developed countries have legal minimum income entitlements. In 1968, James Tobin, Paul A. Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith, and another twelve hundred economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce a system of income guarantees and supplements. Winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics who fully support a basic income include Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, James Meade, Herbert Simon, and Robert Solow. Significantly, this idea cuts across the political spectrum.

Conclusion

A key challenge for modern capitalist societies, alongside the needs to protect the natural environment and enhance the quality of life, is to retain the dynamic of innovation and investment while ensuring that the rewards of the global system are not returned largely to the richer owners of capital. As Paine put it in 1797:

All accumulation, therefore, of personal property, beyond what a man’s own hands produce, is derived to him by living in society; and he owes on every principle of justice, of gratitude, and of civilization, a part of that accumulation from whence the whole came.

But the benefits of ‘living in society’ are not simply through the advantages of cooperation or the division of labour. Modern societies have developed complex institutions that have empowered innovations and massive expansions of wealth. The ultimate and indivisible accumulation is not simply of things, but of knowledge, relations and rules, guarded by law within an adaptable and pluralist polity.

We need to update Paine’s approach to dealing with inequality, to suit modern times.

30 July 2016

Edited 31 July 2016

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

Bibliography

Ackerman, Bruce and Alstott, Anne (1999) The Stakeholder Society (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press).

Atkinson, Anthony B. (2015) Inequality: What Can Be Done? (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Herbert (1999) Recasting Egalitarianism: New Rules for Markets, States, and Communities (London: Verso).

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Herbert (2002) ‘The Inheritance of Inequality’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), Summer, pp. 3-30.

Claeys, Gregory (1989) Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (London and New York: Routledge).

Credit Suisse Research Institute (2012) Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2012 (Zurich: Credit Suisse Research Institute).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Paine, Thomas (1797) Agrarian Justice: Opposed to Agrarian Law and to Agrarian Monopoly (Philadelphia: Folwell).

Paine, Thomas (1945) The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, edited and introduced by Philip S. Foner (New York: Citadel Press).

Piketty, Thomas (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press).

Robinson, Andrew M. and Zhang, Hao (2005) ‘Employee Share Ownership: Safeguarding Investments in Human Capital’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43(3), September, pp. 469-88.

Wilkinson, Richard and Pickett, Kate (2009) The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (London: Allen Lane).

Posted in Common ownership, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Right politics, Socialism, Uncategorized

July 23rd, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

A Worker Cooperative in New York City

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

‘The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works … Nor is the question before us whether the market is a force for good or ill. Its power to generate wealth and expand freedom is unmatched.’

Barack Obama, 2009.

Politicians engage in slogans and sound-bites, but sometimes they reveal their true aims.

The Labour Party is now immersed in a battle for its leadership, and possibly for its survival as a viable political party. Jeremy Corbyn, overwhelmingly elected as leader in 2015 by about sixty per cent of the party membership, has lost the confidence of about eighty per cent of the party’s MPs.

Owen Smith

Owen Smith, Corbyn’s challenger for the Labour leadership, once worked for the private, research-based, pharmaceutical company Pfizer. In response, Corbyn and his allies have been quick to condemn Smith’s association with private enterprise.

Corbyn has always been a supporter of the original version of Labour’s Clause Four, with its aim of ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’. But since he became Labour Leader, he has kept this long-term aim mostly under wraps, highlighting his opposition to austerity economics instead.

However, on 21 July 2016, we had a brief peep under the tarpaulin, showing us Corbyn’s real aims.

Corbyn’s opposition to privately-funded pharmaceutical research

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area.

The ABPI pointed out that the pharmaceutical industry invests more than £88bn a year into research and development for new medicines and vaccines to help fight disease. In the UK this equates to £4.1bn per year of investment in R&D, with the Medical Research Council contributing £770m and research charities £1.3bn.

The pharmaceutical industry is global, and it is difficult to see how the taxpayer-funded UK Medical Research Council could take over the roles of the large private players in this sphere, unless this research was dramatically diminished. As the ABPI pointed out, research in this area has to be a collaboration between industry researchers, academics and clinicians, involving both public and private institutions.

Many successes in the development of drug treatments – including for breast cancer and HIV – have involved collaborations between research-oriented universities, risk-taking companies, concerned charities, government agencies, and so on. Typically these collaborations involve complex synergies and are international in scope.

Corbyn’s proposal that modern levels of pharmaceutical research should be publicly rather than privately funded – within one country – is feasible in neither budgetary nor practical terms.2

But further, in his zeal for the public takeover of research and development, Corbyn has failed to learn one of the crucial economic lessons of the twentieth century, concerning the limitations of largely publicly-owned R&D and need more broadly for a healthy, innovative, private sector.

This lesson is sketched out later below. It concerns the vital role of different forms of private enterprise – from corporations to worker cooperatives, which all have legal autonomy and they sell their products on a market. But first we emphasise that the essential role of the state and the public sector.

The state and the public sector are vital

We should also understand the vital role of the public sector in modern capitalist economists, including in the sphere of research. Numerous authors, including Richard Nelson, Ha-Joon Chang, Erik Reinert, Mariana Mazzucato and myself, have argued that – for several reasons – the state plays an essential, supportive role within modern capitalism.

In practical terms, evidence shows that the most successful economies are those that involve a collaboration of public and private institutions, including for research, development and innovation.

In practical terms, evidence shows that the most successful economies are those that involve a collaboration of public and private institutions, including for research, development and innovation.

For example, the modern patent system is backed up by legal and state powers that protect innovations from plagiarism and provide incentives for private research and creativity. It is an example of the way in which the state can maintain institutions that encourage private research.

There are areas where private enterprise works best, and there are areas where the public sector can be usefully involved. Determining these best areas in each case, is a practical question, involving detailed, complex, ongoing, empirical examination and experimentation.

Instead, Corbyn resorts to ideology, with this prescription: public ownership works best, and even when in doubt, nationalize. This is the mirror image of free-market ideologists, who stipulate: markets work best, and even when in doubt, privatize.

A simplistic ideological debate between private and public ownership dominated the twentieth century. The ‘common ownership’ version of Labour’s Clause Four, which lasted from 1918 to 1995, expressed one side in the debate. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, among many others, took the other side.

A key lesson of the twentieth century is that the dichotomy between public and private provision is misleading. The key question is how they can be usefully combined. Within any useful combination, both private and public enterprise have a crucial role to play. This essay explains why a private sector is vital.

My recent book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism explains why the role of the state is also crucial, even to sustain the institutions that make private enterprise work. But here I concentrate on the case for private enterprise.

The failure of centrally-planned innovation

Any vision of a large-scale planned economy involves assembling information in local or national agencies, and then making decisions based on this information. Proposed innovations and other changes must be appraised, and decisions on their viability must be made.

In their schemes to bring all knowledge together into the hands of planners, advocates of comprehensive planning overlook the time and other difficulties involved in gathering and dealing with available information. Also they give inadequate consideration to how innovations are to be incentivized, tested and promoted.

Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority.

Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority.

Because of diminished competitive pressures, nationalized industries in centrally planned economies, such as the Soviet Union and Mao’s China, have been unimpressive in terms of innovation and flexibility. Why should a committee back innovation or change, especially when it carries risks of failure? Why should they risk their jobs when they have no secure right of additional reward in the case of success?

The economist Peter Murrell showed empirically that the former Communist countries were apparently no less efficient in allocating resources than capitalist economies. Where they lagged was in terms of dynamic efficiency: the ability to innovate. This shortfall is endemic to any system that works on the basis of hierarchical planning, rather than independent enterprise with legal rights to reap and retain rewards.

Whatever the limitations of a market system, it has the advantage that it does not require majority agreement before a decision can be made to produce or distribute a good or service. Private property and contracts permit zones of autonomy within an interrelated system; agents may reach decisions through negotiated contracts with others. The costs and benefits are devolved to individuals or firms.

Through private enterprise it is possible for many technological or institutional innovations to be pioneered without the prior agreement of (democratic) committees or (undemocratic) bureaucrats. This analysis is borne out by experience. The former Soviet-type economies in Russia and China lacked devolved autonomy, secured by private ownership.

Eventually they learned that lesson. The change in China was most dramatic. After the Communist Revolution of 1949, agriculture in China was organized into large collective farms. Other than by threats and bureaucratic bullying, farmers had little incentive to improve productivity. Risky innovation was unwise. Productivity remained low and often there were shortages of food. But Mao Zedong died in 1976, opening up the possibility of reform.

In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.

In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.

China’s spectacular economic growth began when agriculture began to pass into the private control of the peasants after 1978. The Chinese Communist Party endorsed these changes in the rights to use and manage land (while keeping legal title to the land in the hands of the collectives), and also promoted private businesses in rural areas.

China also retained many state-owned enterprises. The state continued to play a major strategic role in economic development. China has demonstrated how viable public and private sectors are essential for growth and innovation in a modern large-scale economy.

The failure of classic socialism

Some version of socialism might work on a small scale. Cooperation can work in this context, based on close, inter-personal interactions. Humans have co-operated in this way, in families and tribal groups, for many thousands of years.

Elinor Ostrom

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Their small size allows participants to monitor each other, to ensure that necessary tasks are carried out and that the interests of the community are served.

Enforcement mechanisms range from praise to punishment. Within these relatively small and cohesive groups, trust and targeted sanctions are mechanisms for encouraging cooperation, reciprocity and compliance with customary rules.

But socialism on a small scale would lack the economies of large-scale production and the technological dynamism of today’s competitive capitalism. Modern medicines and technologically-advanced treatments, requiring extensive funding, risk-taking and research collaboration, could not be developed. With inferior drugs and healthcare, human longevity would be lower than it is today.

In larger socialist societies, individual incentives for effort and innovation are diminished, and compensatory, face-to-face, trust-based mechanisms to sustain cooperation are relatively less effective. When we move from communities of a hundred or so, where it is possible for everyone to know everyone else, to communities of thousands or more, then interpersonal trust and reputation are much less effective at the overall level, and they have to be supplement both other incentives and constraints.

When thousands of people are brought together, and rewards are shared, then there is less incentive to make the extra effort, because the rewards from that additional work would be hugely diluted.

Large private corporations face this problem too. But competitive pressure on the private corporation obliges it to incentivise its workforce in some way, so that most employees pull their weight.

Market competition is absent or much diminished in a centrally planned economy. Instead, the pressure to perform comes from the state. Consequently, strong discipline is necessary to sustain production, and larger-scale socialism engenders authoritarianism and bureaucracy. Twentieth-century evidence strongly supports this analysis.

Those that propose ‘democratic socialism’ in large-scale societies fail to address some key practical questions. How is all the important information to be gathered and transmitted? How are resources to be produced and distributed? How is everyone to be incentivized to work well and to innovate? And if the system is to be ‘democratic’, how would it be possible for everyone involved to vote on every important decision?

Robert Owen

Such practical considerations show that democratic socialism (at least in the classic sense of Robert Owen and Karl Marx, who proposed common ownership and the abolition of private enterprise) is unfeasible in any large-scale complex economy.

While interpersonal interactions can engender cooperation on a small scale, in large-scale societies other mechanisms and incentives are necessary. For dynamism and efficiency, there have to be competition, markets and a large private sector, as well as a state.

Private ownership is also important for political reasons, to create zones of politico-economic power that can countervail state autocracy.

Contrary to the twin, all-or-nothing, ideologies of classical socialism and free-market purism, this leaves open a huge area for economic reform and development. A private sector can be made up of many different kinds of enterprise, including worker cooperatives and social enterprises, as well as more conventional corporations. The state can intervene in a myriad of ways, including the adoption of redistributive taxation and the development of a strong welfare state.

Once all this is understood, then the game changes – irrevocably. Once it is realized that classical socialism cannot work (at least in a humane way) then you have to look for alternatives. Once it is acknowledged that private property and markets are indispensable in large-scale modern economies, then you have to accept them, warts and all. The best that can be done is to minimize their deleterious effects, and to explore viable avenues of institutional reform.

Much of the Labour Party learned this lesson in the era from 1945 to 2015. It adjusted to the mixed economy and began to understand the virtues and indispensability of private enterprise. That lesson seems to be forgotten by a large number of Labour Party members, who continue to support Corbyn and his naïve, outdated ideology. Unless that lesson is learned again, and quickly, then Labour has no future as an electable political party.

23 July 2016

Edited 24 July 2016

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

-

Corbyn added that he was in favour of a National Health Service that is ‘totally public’ with ‘publicly employed people running it’. Is he aware that GPs are not NHS employees but self-employed contractors? If so, is it his intention to make all GPs employees?

-

In an interview on 24 July 2016, Corbyn’s ally John McDonnell backtracked on his leader’s statement, re-admitting a role for private sector pharmaceutical research under some vague notion of ‘democratic control’. He said that Corbyn’s statement had been ‘misinterpreted’. But this dishonest manoeuvring under pressure fails to mask their true aims.

Bibliography

Chang, Ha-Joon (2002) Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective (Anthem Press: London).

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1944) The Road to Serfdom (London: George Routledge).

Mazzucato, Mariana (2013) The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (London and New York: Anthem).

Murrell, Peter (1991) ‘Can Neoclassical Economics Underpin the Reform of Centrally Planned Economies?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(4), Fall, pp. 59-76.

Nelson, Richard R. (1981) ‘Assessing Private Enterprise: An Exegesis of Tangled Doctrine’, Bell Journal of Economics, 12(1), pp. 93-111.

Nelson, Richard R. (2003) ‘On the Complexities and Limits of Market Organization’, Review of International Political Economy, 10(4), November, pp. 697-710.

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Reinert, Erik S. (2007) How Rich Countries Got Rich … And Why Poor Countries Stay Poor (London: Constable).

Zhou, Kate Xiao (1996) How the Farmers Changed China (Boulder, CO: Westview Press)

Posted in Common ownership, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Right politics, Robert Owen, Socialism, Uncategorized

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me. Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Corbyn is right:

Corbyn is right:  There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail. The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said: Even small successes –

Even small successes –

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership.

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership. Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself. Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral. Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada.

Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada. To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes.

To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes. Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area. Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority.

Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority. In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.

In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.