November 18th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

“One of the most important essays you will read in 2016” @Rokewood

What caused the election of Donald Trump? I am deeply dissatisfied by some of the quick answers to this question.

The leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition had an instant answer. Jeremy Corbyn blamed the left’s association “with the forces of globalisation during the Obama administration”. Instead, he insisted, we need to reject “that free market, economic thinking, which processed deindustrialisation in Britain”.

Naomi Klein

Others used different words on the same “free market” theme. Naomi Klein put it bluntly: “the force most responsible” for Trump’s success was “neoliberalism”. This worldview, “fully embodied by Hillary Clinton and her machine”, was “no match for Trump-style extremism.”

Trump won over US voters because: “Under neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatisation, austerity and corporate trade, their living standards have declined precipitously.”

The Guardian columnist George Monbiot followed with a historical piece, claiming that “the events that led to Donald Trump’s election started in England in 1975”, when Margaret Thatcher embraced the free-market “neoliberal” philosophy of Friedrich Hayek. This was a harbinger of the global rise of free-market thinking that allegedly wrought havoc in recent years.

Both Klein and Monbiot argue that Trump capitalised on the failure of other politicians to deal with the adverse effects of neoliberalism.

There is no doubt that the global expansion of capitalism in recent decades has been hugely disruptive, shifting millions of manufacturing jobs to East Asia. In the absence of adequate retraining and investment, it has led to declining opportunities for large swathes of the working population in North America and Europe.

Trump tapped into working class discontent. In important respects his policies are not neoliberal, by any reasonable definition of that term. In his campaign, Trump used anti-neoliberal, protectionist slogans such as high import tariffs and closed borders.

George Monbiot

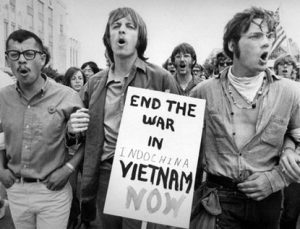

But why did it take so long for people to react to “neoliberalism” and vote in this way? As Monbiot argued, the current so-called “neoliberalism” got under way in the 1970s. It accelerated after the beginning of economic reform in China in 1978 and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in1989. The whole world was then opened up for trade.

But while right-populist movements had emerged, they were then far from power. Tony Blair won a landslide election in 1997 and increased public spending on welfare, education and health. Three years after Blair had won a third election, the United States elected its first black President.

If neoliberalism and stagnant living standards had been around since the 1970s, then why did it take 40 years for a Trump-like demagogue to be elected? The political wind swung decisively to the right more recently, after the Great Crash of 2008.

But it is also difficult to explain Trump’s populist success as a targeted reaction to the financial crash. The removal of some banking regulations, by Bill Clinton in the US and Gordon Brown in the UK, did exacerbate the lending boom that led to the crash of 2008.

Yet, despite his protectionism, Trump offers still more deregulation. He is not targeting the bankers as part of the “elite”. On the contrary, he has pledged to repeal the Dodd-Frank Act, which was designed to curb some of the excesses of the financial sector. As Larry Elliott put it: “This looks curious for someone trying to surf a tidal wave of populist anger against the bankers.”

Putting the blame on “neoliberalism” underestimates the way in which outsiders such as Trump and Farage have created populist movements that blame “the elite” and offer simplistic solutions, such as to “curb immigration”. Blaming “neoliberalism” underestimates the pernicious influences of racism and anti-Muslim prejudice. Simplistic economic explanations of Trump’s victory ignore much stronger evidence of other factors at work.

Putting the blame on “neoliberalism” underestimates the way in which outsiders such as Trump and Farage have created populist movements that blame “the elite” and offer simplistic solutions, such as to “curb immigration”. Blaming “neoliberalism” underestimates the pernicious influences of racism and anti-Muslim prejudice. Simplistic economic explanations of Trump’s victory ignore much stronger evidence of other factors at work.

The Pavlovian leftist response of blaming markets or “neoliberalism” for “all our problems” is far off the mark.

What is neoliberalism?

Monbiot is keen to identify “neoliberals” such as Hayek as the villains. According to Monbiot:

“Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. … Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone.”

I shall pass over the many flaws in the essay from which the above passage is quoted. Monbiot conflates the different views of Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, and he is inaccurate on several details. Note also that Monbiot does not highlight deregulation of the financial sector in this passage.

After taking on board Monbiot’s definition of neoliberalism, let us consider the extent to which it has been achieved in the real world.

Has neoliberalism been achieved in practice?

Monbiot described how in the 1970s “elements of neoliberalism, especially its prescriptions for monetary policy, were adopted by Jimmy Carter’s administration in the US and Jim Callaghan’s government in Britain.” He is unclear on the details, but presumably in part he refers to Callaghan’s embrace of monetarist ideas from 1976 to 1979.

Milton Friedman

Monetarism, incidentally, is not obviously the same as neoliberalism. While monetarists such as Friedman were free-marketeers, monetarism’s central claim is that the main cause of inflation is the rise in the money supply – a thesis that (as Friedman himself recognised) could also apply to a planned economy. Indeed, this central monetarist tenet was adopted by some Marxist economists.

“After Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan took power, the rest of the [neoliberal] package soon followed: massive tax cuts for the rich, the crushing of trade unions, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services.”

He is right. Albeit to different degrees in different countries, these things happened.

But go back to Monbiot’s checklist definition of neoliberalism, as quoted above. He saw neoliberalism as minimising “tax” not simply “tax cuts for the rich”. Has this happened?

Ronald Reagan & Margaret Thatcher

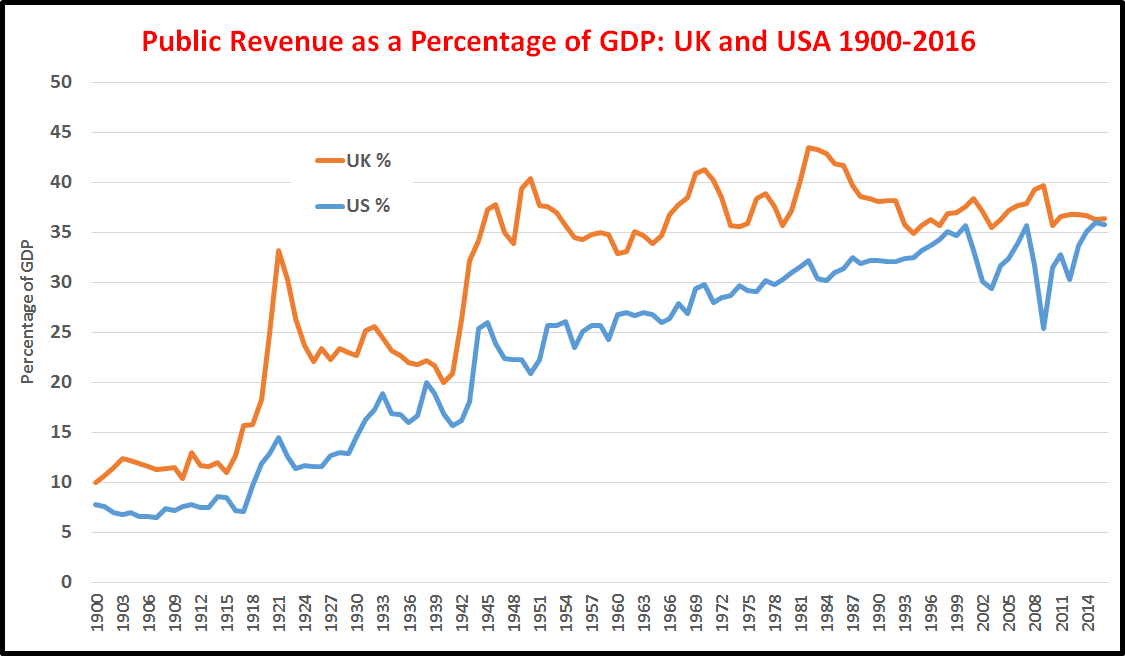

Margaret Thatcher reduced taxation for the rich. But the overall tax burden (all taxes as a percentage of GDP) rose during her period of office. This figure fell in the 1990s and has fluctuated from 1997 in a range between 35 per cent and 38 per cent of GDP. The UK austerity governments since 2010 have not reduced the overall tax take significantly.

Similarly, Ronald Reagan began by cutting income taxes for the rich, but ended his eight-year term of office with a Federal percentage tax take almost identical to that of his predecessor Jimmy Carter, and slightly above the average for the entire 1970-2009 period.

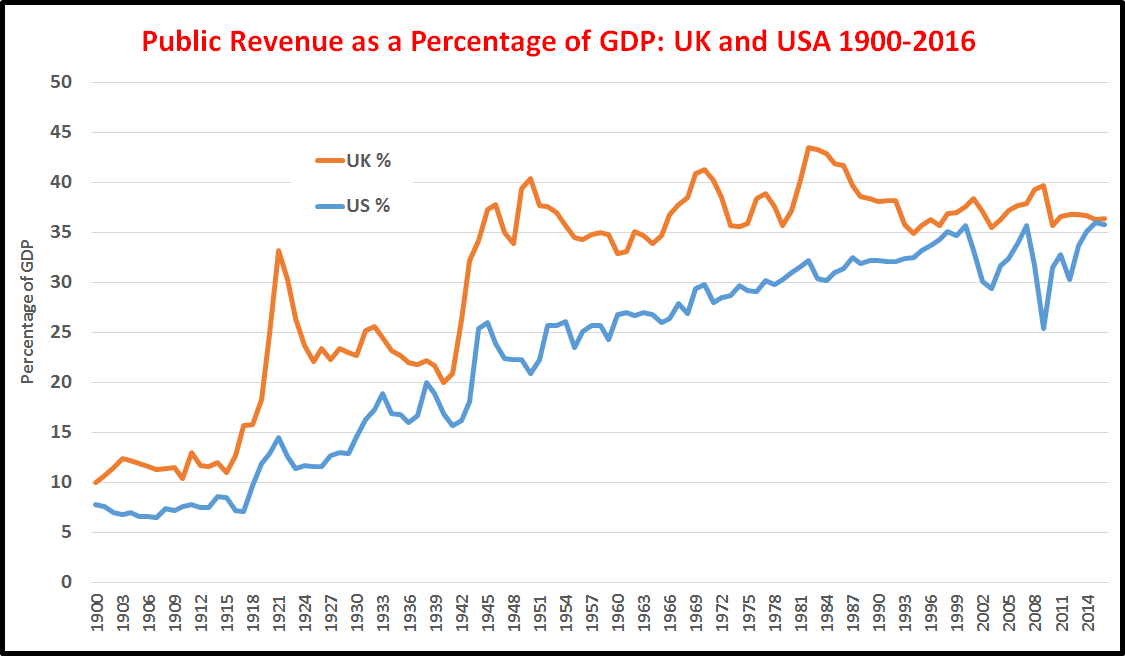

The “neoliberal” mission of massive overall tax cuts was not achieved under Thatcher or Reagan, or under subsequent administrations. Put in a longer historical perspective, taxation and public spending in the UK and USA today are much higher than they were before the Second World War.

The above figure shows the tax revenues, from national, state and local government combined, for the UK and the USA from 1900 to 2016. The alleged era of “neoliberalism” from the 1970s has not been associated with declining tax revenues. If anything, the “neoliberal” era of a minimal state was pre 1914, not post-1975.

What is characteristic of fiscal policy in the UK and USA is not the alleged “neoliberal” overall reduction of taxation but a lightening of taxation on the rich, and a failure to redistribute sufficiently, in the face of widening inequality.

Klein is probably right to suggest: “A good chunk of Trump’s support could be peeled away if there were a genuine redistributive agenda on the table.” But she, with Corbyn and Monbiot, are wrong to chime in with the crude anti-market mantras that have disabled the Left for 180 years. In building a redistributive agenda we must look to Thomas Paine, rather than Robert Owen or Karl Marx.

Privatisation: against dogma

By contrast, Monbiot’s other point, about growing privatisation since the 1970s, has been borne out by the evidence. In the UK, USA and much of the world there has been massive privatisation and outsourcing of public services.

Unlike any false claim that “neoliberalism” has reduced overall taxes, the increase of privatisation is manifest. In addition, it has sometimes led to deleterious consequences including lower pay for workers and a reduced quality of services.

Unlike any false claim that “neoliberalism” has reduced overall taxes, the increase of privatisation is manifest. In addition, it has sometimes led to deleterious consequences including lower pay for workers and a reduced quality of services.

But Corbyn and Monbiot speak and write as if privatisation is necessarily bad – always and everywhere it is seen as a negative policy. This doctrinaire stance simply inverts the claim of the crudest free marketeers, who claim that state provision is always bad and that private provision is always good. The Corbyn-Monbiot stance simply turns this upside-down. It is equally dogmatic. It is based on ideology, not evidence.

Regarding markets as always bad, amounts to agoraphobia or fear of markets (from the Greek words agora for market, and phobia for fear). This is an inversion of the kratophobia of the free-marketeers – a fear of government or of the state.

Instead of these ideologically-driven, simplistic positions, it is necessary to be more pragmatic. Some privatisations work. Others do not. Some state provision is effective. Some is wasteful and inefficient. We need to look at individual cases to understand why.

There are many case studies to look at and they are too wide-ranging to be reviewed here. A good start would be to look at an important early article on privatisation by John Goodman and Gary Loveman in the Harvard Business Review. They wrote:

“the issue is not simply whether ownership is private or public. Rather, the key question is under what conditions will managers be more likely to act in the public’s interest … managerial accountability to the public’s interest is what counts most, not the form of ownership.”

Goodman and Loveman argued that profits and the public interest overlap best when the privatised organisation is in a competitive market. Competition from other companies can discipline managerial behaviour. Consequently, there is little point in privatisation if competition is lacking.

Subsequent research has shown that other factors are involved as well. Instead of being driven by dogma, we need to be pragmatic and experimental, taking account of research.

Jeremy Corbyn

You may respond that Corbyn is pragmatic, because he has declared that he is in favour of a mixed economy: he accepts a private as well as a public sector. But notice the imbalance in his presentations. He treats public provision as ideal, and the private sector as an expedient to be tolerated, at least for a while.

Corbyn says he accepts a mixed economy, but he has offered has no defence of private sector. His “mixed economy” could be a stopping point on the road to a fully-socialist planned economy, where private enterprise is pushed to the side-lines.

Declining public provision?

Ken Loach’s moving film, I, Daniel Blake, portrays the heart-breaking human consequences of the UK Conservative government’s shredding of the welfare safety net for the poor. Attempts to reduce public spending in many countries have led to millions of human tragedies like this.

Ken Loach’s moving film, I, Daniel Blake, portrays the heart-breaking human consequences of the UK Conservative government’s shredding of the welfare safety net for the poor. Attempts to reduce public spending in many countries have led to millions of human tragedies like this.

Doctrinaire austerity policies – which fail in their own terms because they depress economic demand for goods and services and create more unemployment – have been adopted by many governments and imposed by the European Union.

All this is real, and tragic. Millions have suffered because of such misguided policies. But we should not jump to the conclusion that “neoliberalism” has been successful in moving toward a minimal economic role for the state.

All this is real, and tragic. Millions have suffered because of such misguided policies. But we should not jump to the conclusion that “neoliberalism” has been successful in moving toward a minimal economic role for the state.

In my book Conceptualizing Capitalism I examined differences and changes in public social spending in different developed countries from 1980 to 2005, using OECD data. The principal components of public social spending include health services, old age benefits, unemployment benefits, incapacity-related benefits, family support, active labour market public programs, and housing benefits.

Amounts of public spending as percentages of GDP (in 1980 and 2005) are shown below.

|

1980 |

2005 |

change |

| Australia |

10.3 |

16.5 |

+6.2 |

| Austria |

22.4 |

27.1 |

+4.7 |

| Belgium |

23.5 |

26.5 |

+3.0 |

| Canada |

13.7 |

16.9 |

+3.2 |

| Denmark |

24.8 |

27.7 |

+2.9 |

| Finland |

18.1 |

26.2 |

+8.1 |

| France |

20.8 |

30.1 |

+9.3 |

| Germany |

22.1 |

27.3 |

+5.2 |

| Italy |

18.0 |

24.9 |

+6.9 |

| Japan |

10.2 |

18.5 |

+8.3 |

| Netherlands |

24.8 |

20.7 |

–4.1 |

| Norway |

16.9 |

21.6 |

+4.7 |

| Portugal |

9.9 |

23.0 |

+13.1 |

| Spain |

15.5 |

21.1 |

+5.6 |

| Sweden |

27.1 |

29.1 |

+2.0 |

| Switzerland |

13.8 |

20.2 |

+6.4 |

| UK |

16.5 |

20.5 |

+4.0 |

| US |

13.2 |

16.0 |

+2.8 |

Public Social Spending as Percentage of GDP in Selected Countries

Most countries increased their public social spending, during a period when the ideology of privatization was resurgent. The Netherlands is an exception. Note that the increases in public social spending are not explained by rises in unemployment benefit, because generally this comprises a small proportion of public social spending.

Of course, it needs to be emphasised that there is an ideologically-driven agenda that has led to deep cuts in some welfare and has been gravely damaging for the poor. But we are far from re-entering the era of the minimal state.

Pursuing unicorns

Much of the hysteria against “neoliberalism” draws from the Left’s deep rooted antipathy to markets. Let’s briefly address this.

First, they may be alternatives to markets in modern, large-scale economic systems but they would greatly out-do the miseries inflicted on the fictional Daniel Blake and his millions of real-world counterparts.

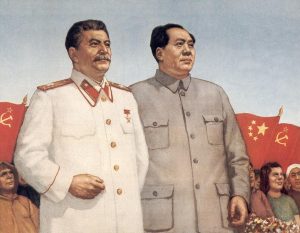

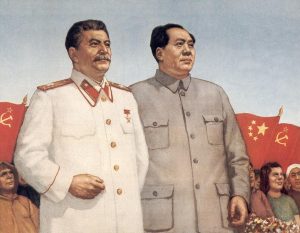

Karl Marx

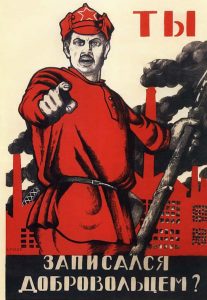

Every attempt to get rid of markets, since Robert Owen and Karl Marx proclaimed their redundancy in the nineteenth century, has led to famine, repression and the termination of democracy. Look to Stalin’s Russia, Mao’s China, Cambodia, Cuba and Venezuela. Twentieth-century Communism resulted in over 90 million deaths.

In the light of twentieth-century experience it would be worse than foolhardy to make yet another attempt to minimise markets, or as Klein oddly put it, “corporate trade”.

A better way is possible, but it involves taming and supplementing markets, not repressing them. It means regulating corporations, not casting them as sorcerers of evil. But sadly, agoraphobia still afflicts many on the left.

“It seems to me that the questions we urgently need to ask ourselves are these: is totalitarianism the only means of eliminating capitalism? If so, and if … we abhor totalitarianism, can we continue to call ourselves anti-capitalists? If there is no humane and democratic answer to the question of what a world without capitalism would look like, then should we not abandon the pursuit of unicorns, and concentrate on capturing and taming the beast whose den we already inhabit?”

Excellent. But since then he has gone down the rocky road of blaming “neoliberalism” for “all our problems”. Without defending some role for private property or markets, he thereby allies himself with the many leftists who now describe anyone defending private property or markets as “neoliberal”.

Has Monbiot now abandoned the idea of taming the capitalist beast? Does he wish to kill it instead?

In April 2016 he wrote: “Every invocation of Lord Keynes is an admission of failure.” So he junked the best macroeconomic theory we have for limiting some of the excesses of capitalism. His grounds for doing so were these:

“Keynesianism works by stimulating consumer demand to promote economic growth. Consumer demand and economic growth are the motors of environmental destruction.”

John Maynard Keynes

Wrong. “Consumer demand and economic growth” can destroy the planet, but only if that demand and growth relate to non-renewable material resources. Much demand and growth in modern economies is for services. Intangible assets now make up much of corporate wealth. For example, there are demands for information and education, and such services are added to GDP. There is no necessary reason why economic growth in a modern information-rich economy should ruin the planet. Keynes is still relevant.

Those that have pursued unicorns have imagined that it is possible to design a better system than capitalism. Monbiot says the same, declaring that for the Left

“the central task should be to develop an economic Apollo programme, a conscious attempt to design a new system, tailored to the demands of the 21st century.”

This puts him in full, unicorn-chasing mode. One of the biggest mistakes by early socialists was to ignore the massive complexity of modern economic systems and attempt to “design a new system” at the behest of some utopian dreamer.

Instead, what is required is careful, incremental, experimental change, retaining the flexibility and devolved autonomy afforded by widespread private property. This autonomy allows for multiple experiments and deeper learning from mistakes.

While state intervention is necessary, no complete or adequate overall “design” is possible, because of the way much knowledge is irretrievably dispersed throughout the economy. The economies of the twenty-first century are more knowledge-intensive than those before. Hence the possibilities of comprehensive central planning or “design” are even more limited.

Neoliberalism and economic man

“as modern psychology and neuroscience make abundantly clear – human beings, by comparison with any other animals, are both remarkably social and remarkably unselfish. The atomisation and self-interested behaviour neoliberalism promotes run counter to much of what comprises human nature.”

The first sentence is valid and important. The second is simplistic. As I elaborate in my book From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities, strong evidence from psychology, evolutionary biology and primatology shows that the picture of self-seeking “economic man”, which dominated mainstream economics until recently, is deeply flawed.

The first sentence is valid and important. The second is simplistic. As I elaborate in my book From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities, strong evidence from psychology, evolutionary biology and primatology shows that the picture of self-seeking “economic man”, which dominated mainstream economics until recently, is deeply flawed.

But that does not mean that we can or should get rid of markets. Our capacities for cooperation evolved culturally and genetically because our ancestors hunted and foraged in groups, rarely numbering more than 200 individuals, for millions of years. Relying on emotions and facial expressions, we developed sophisticated social mechanisms to engender trust and cooperation, and to enforce social rules.

As larger-scale cities emerged about 14,000 years ago, these face-to-face mechanisms could no longer be relied upon exclusively to regulate social interactions. Institutions such as law, property and contract were developed to deal with these more impersonal, non-familial, transactions.

Every human civilisation that has developed has relied on property, trade and contracts. These require different enforcement mechanisms, but they too require measures of trust and moral obligation, as Adam Smith made clear in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. The idea that markets inevitably corrode away all social ties is mistaken.

Even the Soviet-style economies of the twentieth century relied on some private property and trade. They failed because state bureaucracy stifled autonomy and innovation. China grew rapidly when it expanded the private sector after 1978.

Of course, the spread of the market would be detrimental if it invaded all our social relations, attempting to put prices on love and friendship and reducing everything else to money transactions. But a system of private property provides a degree of autonomy that is required to maintain non-market interactions at home and at work. Successful corporations create islands of cooperation and teamwork within their organisational boundaries.

Impersonal relations occur in bureaucracies as well as in markets. Large-scale systems of national planning also make much interaction impersonal. People become atomised; they become numbers, to be processed by bureaucrats and computers.

Impersonal relations occur in bureaucracies as well as in markets. Large-scale systems of national planning also make much interaction impersonal. People become atomised; they become numbers, to be processed by bureaucrats and computers.

The experience of centrally-planned economies in Russia, China and Eastern Europe shows that systems of state planning can be cesspits of human alienation and corruption, governed impersonally by disillusioned bureaucrats and corrupt state officials. I recommend the film The Lives of Others for a glimpse into that dark world.

Abandoning neoliberalism

I have written at further length elsewhere on the limits to markets. I accept Hayek’s explanation that comprehensive overall planning is dysfunctional. But I do not accept that everything should or can become a monetary transaction in its place.

Indeed, the growing use of information in a capitalist economy puts limits on the role of information as property. Furthermore, the very freedom of waged employees means that there are constraints on entering into contracts for future work. There are limited futures markets for labour. For such reasons, capitalism can never be a 100 per cent market system.

Hayek failed to acknowledge fully the limits to markets. Such free marketeers are the mirror-image of socialists who fail to acknowledge adequately that there are limits to common ownership. We have to transcend both agoraphobia and kratophobia.

Agoraphobics react adversely to any tolerance of markets. Hence economic interventionists such as Tony Blair, and supporters of public healthcare such as Hillary Clinton, have recently and frequently been accused of being neoliberals. This is misleading and absurd.

As Colin Talbot has pointed out, “neoliberalism” has become “a term of abuse” to be used against “any type of pro-market reform or political position that recognizes markets may – in the right circumstances – be a good thing”. Consequently, everyone “from moderate social democrats to the most lurid free-marketeers gets lumped together under a convenient ‘neoliberal’ label.”

In a brilliant survey of its usage since the 1980s, Rajesh Venugopal concluded that “neoliberalism has become a deeply problematic and incoherent term that has multiple and contradictory meanings, and thus has diminished analytical value.”

Some may wish to retain the “neoliberal” label, to apply it to those free marketeers who attempt to shrink radically the size of the state, and to privatise anything that walks. The definition could be further sharpened by adding advocacy of economic austerity. It could also could be sharpened by including deregulation of the financial sector.

But such nuances have been lost in a global storm of “neoliberal” accusations. Klein and Monbiot have added some force and authority to this widening tempest.

But such nuances have been lost in a global storm of “neoliberal” accusations. Klein and Monbiot have added some force and authority to this widening tempest.

They do not confine their accusations to the likes of Hayek. Most seriously, they pointed the “neoliberal” finger at Hillary and Bill Clinton, as Corbyn made the “forces of globalisation” jibe at Barack Obama.

If it means anything, neoliberalism is an ideology and only partly a reality. Austerity and welfare cuts have wreaked havoc, but markets and private enterprise have lifted millions out of poverty. Agoraphobic accusations of “neoliberalism” miss the latter point.

“Neoliberalism” gave us Trump

We may ask: what part did the accusers of “neoliberalism” have to play in Trump’s victory? The constant tainting of Hillary Clinton as a “neoliberal” may have helped to persuade many Democratic supporters to stay at home. We know from the data that the below-par turnout by Democrats – especially by the young – was decisive in losing those swing states.

Tainting Hillary Clinton as a “neoliberal” could have played a part in clinching Trump’s success. If so, “neoliberalism” gave us Trump, but not in the way that Klein and Monbiot suggest.

18 November 2016

Minor edits – 19, 25, 30 November, 15, 28 December 2016

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

Bibliography

BBC News (2016) ‘Jeremy Corbyn outlines Labour’s vision of a “new economics”’, 21 May. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-36351149.

Chantrill, Chrisopher (2016a) ‘UK Public Revenue’. http://www.ukpublicrevenue.co.uk/uk_national_revenue_analysis

Chantrill, Chrisopher (2016b) ‘US Government Revenue’. http://www.usgovernmentrevenue.com/revenue_history

Elgot, Jessica (2016) ‘Corbyn backs reduction of NATO presence along Russia’s borders’, The Guardian, 13 November. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/13/jeremy-corbyn-hints-at-reducing-nato-presence-russia-putin?CMP=share_btn_tw.

Elliott, Larry (2016) ‘Trump’s economic view is far from neoliberal, but it rides a populist wave’, The Guardian, 31 July. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jul/31/trumps-economic-view-is-far-from-neoliberal-but-it-rides-a-populist-wave.

Goodman, John B. and Loveman, Gary W. (1991) ‘Does privatization serve the public interest?’ Harvard Business Review, November-December. https://hbr.org/1991/11/does-privatization-serve-the-public-interest.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2013) From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities: An Evolutionary Economics without Homo Economicus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Johnson, Christopher (1991) The Economy under Mrs Thatcher (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Klein, Naomi (2016) ‘It was the Democrat’s embrace of neoliberalism that won it for Trump’, The Guardian, 9 November. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/09/rise-of-the-davos-class-sealed-americas-fate.

Monbiot, George (2003) ‘Rattling the Bars’, The Guardian, 18 November. See http://www.monbiot.com/2003/11/18/rattling-the-bars/.

Monbiot, George (2016a) ‘Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems’, The Guardian, 15 April. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot.

Monbiot, George (2016b) ‘Neoliberalism: the deep story that lies beneath Donald Trump’s triumph’, The Guardian, 14 November. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/14/neoliberalsim-donald-trump-george-monbiot.

O’Hara, Glen (2016) ‘Stop saying that Trumpism is about economics’, 15 November. http://publicpolicypast.blogspot.co.za/2016/11/stop-saying-that-trumpism-is-about.html.

Pagano, Ugo (2014) ‘The Crisis of Intellectual Monopoly Capitalism’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(6), November, pp. 1409-29. http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/08/04/cje.beu025.

Sahadi, Jeanne (2010) ‘Taxes: What people forget about Reagan’, CNN Money, 12 September. http://money.cnn.com/2010/09/08/news/economy/reagan_years_taxes/.

Talbot, Colin (2016) ‘The myth of neoliberalism’, 31 August. https://colinrtalbot.wordpress.com/2016/08/31/the-myth-of-neoliberalism/.

Velasco, Andrès (2016) ‘The Real Roots of Populism’, Project Syndicate, 28 July. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/real-roots-of-populism-by-andres-velasco-2016-07?backaction=

Venugopal, Rajesh (2015) ‘Neoliberalism as a Concept’, Economy and Society, 44(2), pp. 165-87. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013356.

Posted in Common ownership, Donald Trump, George Monbiot, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Naomi Klein, Nationalization, Populism, Private enterprise, Right politics, Tony Blair, Uncategorized

July 30th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Once upon a time, all socialists saw the ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’ as their primary aim. Many die-hards still do.

Others now focus instead on reducing inequalities of power, wealth and income. Some past or present contenders for leadership of the UK Labour Party, including Yvette Cooper and Owen Smith, have argued that the party’s aims in Clause Four of its constitution, should be rewritten to give greater emphasis to equality.

Smith has gone even further, to declare that Labour should focus on ‘equality of outcomes’ and not simply equality of opportunity. He proposed a wealth tax and an increase of the top rate of income tax to 50 per cent. Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership team claimed that they had already adopted these policies.

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership.

Given the huge and growing inequalities within modern capitalism, this focus on inequality is a positive move. But concern about inequality has never been confined to socialism. Ritual incantation of the aim for a ‘socialist’ future within the Labour Party may divert attention from measures that can be implemented within capitalism and without widespread common ownership.

We also need to look at the basic drivers of inequality within capitalism. We must consider what can be done, within this system, and short of some mythical socialist future.

The practicalities of trying to reduce inequality within capitalism have to be addressed. If higher taxes are part of the solution, then somehow, in a democracy, people have to be persuaded to adopt them. Additional measures to help reduce inequality should be devised.

Furthermore, talk of ‘equality of outcomes’ is ill-advised. Are we really going to give everyone the same income and wealth, thus removing incentives for creativity and hard work? Is the communist utopia – ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his need’ – practical, or even desirable?

The aim should be to dramatically reduce inequality, not to eliminate it. Incentives for hard work and enterprise should be retained.

Shifting the focus from common ownership to the reduction of inequality is an important step forward. But the analysis of causes, and the design of policy, have to be much more sophisticated.

The problem of inequality

At least nominally, capitalism embodies and sustains an Enlightenment agenda of freedom and equality. Typically there is freedom to trade and equality under the law, meaning that most adults – rich or poor – are formally subject to the same legal rules. But with its inequalities of power and wealth, capitalism darkens this legal equivalence.

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett showed multiple deleterious effects of inequalities of income and wealth. Using data from twenty-three developed countries and from the separate states of the United States, they observed negative correlations between inequality, on the one hand, and physical health, mental health, education, child well-being, social mobility, trust and community life, on the other hand. They also found positive correlations between inequality and drug abuse, imprisonment, obesity, violence, and teenage pregnancies. They suggested that inequality creates adverse outcomes through psycho-social stresses generated through interactions in an unequal society.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century, and by me in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism, show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

But first we must be clear about the drivers of inequality within the system. What are the mechanisms within capitalism that exacerbate inequalities of income or wealth?

Some inequality results from individual differences in talent or skill. But this cannot explain the huge gaps between rich and poor in many capitalist countries. Much of the inequality of wealth found within capitalist societies results from inequalities of inheritance. The process is cumulative: inequalities of wealth often lead to differences in education, economic power, and further inequalities in income.

Do markets create inequality?

To what extent can inequalities of income or wealth be attributed to the fundamental institutions of capitalism, rather than a residual landed aristocracy, or other surviving elites from the pre-capitalist past? A familiar mantra is that markets are the source of inequality under capitalism. Can markets be blamed for inequality?

In real-world markets different sellers or buyers vary hugely in their capacities to influence prices and other outcomes. When a seller has sufficient saleable assets to affect market prices, then strategic market behaviour is possible to drive out competitors.

Would more competition, with greater numbers of market participants, fix this problem? If markets per se are to be blamed for inequality, then it has to be shown that competitive markets also have this outcome. Unless we can demonstrate their culpability, blaming competitive markets for inequalities of success or failure might be like blaming the water for drowning a weak swimmer.

To demonstrate that competitive markets are a source of inequality we would have to start from an imagined world where there was initial equality in the distribution of income and wealth, and then show how markets led to inequality. I know of no such theoretical explanation.

Markets involve voluntary exchange, where both parties to an exchange expect benefits. One party to the exchange may benefit more than the other; but there is no reason to assume that individuals who benefit more, or benefit less (in one exchange) will generally do so. And if some traders become more powerful in the market than others, then its competitiveness is reduced.

The sources of inequality within capitalism

So if markets per se are not the root cause of inequality under capitalism, then what is? A clear answer to this question is vital if effective policies to counter inequality are to be developed. Capitalism builds on historically-inherited inequalities of class, ethnicity, and gender. By affording more opportunities for the generation of profits, it may also exaggerate differences due to location or ability. Partly through the operation of markets, it can also enhance positive feedbacks that further magnify these differences. But its core sources of inequality lie elsewhere.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral.

By contrast, capitalists may use their property to make profits, and as collateral to borrow money, invest and make still more money. Differences become cumulative, between those with and without collateralizable assets, and between different amounts of collateralizable wealth. Even when workers become home-owners with mortgages, the wealthier can still race ahead.

Unlike owned capital, free labour power cannot be used as collateral to obtain loans for investment. At least in this respect, capital and labour do not meet on a level playing field, this asymmetry is a major driver of inequality.

The foremost generator of inequality under capitalism is not markets but capital. This may sound Marxist, but it is not. I define capital differently from Marx and from most other economists and sociologists. My definition of capital corresponds to its enduring and commonplace business meaning. (Piketty’s definition is also similar to mine.) Capital is money, or the realizable money-value of collateralizable property. Unlike labour, capital can be used as collateral and the loan obtained can help generate further wealth.

Because workers are free to change jobs, employers have diminished incentives to invest in the skills of their workforce. Especially as capitalism becomes more knowledge-intensive, this can create an unskilled and low-paid underclass and further exacerbate inequality, unless compensatory measures are put in place. A socially-excluded underclass is observable in several developed capitalist countries.

Another source of inequality results from the inseparability of the worker from the work itself. By contrast, the owners of other factors of production are free to trade and seek other opportunities while their property makes money or yields other rewards. This puts workers at a disadvantage. Through positive feedbacks, even slight disadvantages can have cumulative effects.

None of these core drivers of inequality can be diminished by extending markets or increasing competition. These drivers are congenital to capitalism and its system of wage labour. If capitalism is to be retained, then the compensatory arrangements that are needed to counter inequality cannot simply be extensions of markets or private property rights.

These ineradicable asymmetries between labour and capital mean that ultra-individualist arguments against trade unions are misconceived. In a system that is biased against them, workers have a right to organize and defend their rights, even if it reduces competition in labour markets.

The relevance of Thomas Paine

Contrary to a widespread myth, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was a liberal rather than a socialist. There is no support for common ownership in his writings. Instead he support private enterprise and a market economy.

But over two hundred years ago, he set out arguments and methods for reducing inequality. Paine recognised that ownership of property was vital, to provide incentives for the generation of wealth and to provide a means for its fairer distribution.

Paine argued for an inheritance tax, but balanced this by a grant to each adult at reaching the age of maturity. In this way, wealth would be recycled from the dead to the young, providing greater equality of opportunity across the board. Paine also advocated welfare provision and a guaranteed pension for those over 50.

Much of the wealth in Paine’s time was in land. Land and buildings are immobile, and can be readily assessed and taxed. But capital is fleet-footed and covert: it can be easily moved around the world or hidden in foreign accounts. Land ownership is still highly concentrated in a few hands, along with much additional wealth.

Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada.

Today we face problems of inequality even greater than those addressed by Paine. In the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada.

Although there are important variations, other developed countries show similar patterns of inequality within this range. The problem is extreme in the USA. Lower levels of inequality elsewhere are far from satisfactory, but they indicate what might be politically feasible for the currently more unequal countries.

Spreading property

Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott took up Paine’s agenda in their proposal for a ‘stakeholder society.’ They argued that ‘property is so important to the free development of individual personality that everybody ought to have some’. They echoed Francis Bacon: ‘Wealth is like muck. It is not good but if it be spread.’

To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes.

To this end, home ownership is of positive value, as a means of widely extending ownership of collateralizable property. But there also needs to be a substantial amount of social housing available for rent, to cater for those unable to afford to buy their own homes.

Significantly, the Right has promoted home ownership, while it has often been rebutted by the Left. This resistance comes from the Left’s old-fashioned, over-extended collectivism. By contrast, it is important for the Left to champion home ownership within an egalitarian and redistributive political programme.

When Margaret Thatcher introduced the ‘right to buy’ for tenants in social housing in 1980, Labour responded in its 1983 General Election Manifesto with a pledge to reverse these sales. But by 1985 Labour had abandoned this position.

Recycling wealth across generations

Ackerman and Alstott stressed progressive taxes on wealth rather than on income. Echoing Paine, they proposed a large cash grant to all citizens when they reach the age of majority, around the benchmark cost of taking a bachelor’s degree at private university in the United States. This grant would be repaid into the national treasury at death. To further advance redistribution, they argued for the gradual implementation of an annual wealth tax of two percent on a person’s net worth above a threshold of $80,000. Like Paine, they argued that every citizen has the right to share in the wealth accumulated by preceding generations. A redistribution of wealth, they proposed, would bolster the sense of community and common citizenship.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

People will be more ready to accept wealth taxation if they have earlier benefitted from a large cash grant in their youth. Wealth would by recycled to younger generations rather than syphoned away. The more fortunate or successful can be persuaded to give up some of their advantages if they see the benefits for society as a whole.

A related proposal, also redolent of Paine, was launched by the British Labour Government in 2005. It introduced a Child Trust Fund with the aim of ensuring every child has savings at the age of 18, giving every child a financial boost that they could use for the purposes of education or enterprise. Children received an initial £250 subscription from the government. Family and friends could top up these trust funds. The child would attain control of the fund at age 18. Withdrawals could then be made but be exempt from taxation. A weakness of this particular scheme was its timidity. A greater government subscription would have been more redistributive and egalitarian in its consequences. Child Trust Funds were opposed by the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, and abolished after they came to power in a coalition in 2010.

Extending education and share ownership

In the economy, there are many ways of spreading power and influence more broadly. The idea of extending employee shareholding is growing in popularity. This is a flexible strategy for extending ownership of revenue-producing assets in society. In the USA alone, over ten thousand enterprises, employing over ten million workers, are part of employee-ownership, stock bonus, or profit-sharing schemes. Employee ownership can increase incentives, personal identification with the enterprise, and job satisfaction for workers. The evidence suggests that when employee-ownership schemes and some employee participation in decision-making are combined, greater increases in profitability and productivity can be obtained.

As modern capitalist economies become more knowledge-intensive, access to education to develop skills becomes all the more important. Those deprived of such education suffer a degree of social exclusion, and, unless it is addressed, this problem is likely to get worse. Widespread skill-development policies are needed, alongside integrated measures to deal with job displacement and unemployment.

A universal basic income

The need for ongoing education is one argument for a basic income guarantee. Such a basic income would be paid to everyone out of state funds, irrespective of other income or wealth, and whether the individual is working or not. It is justified on the grounds that individuals require a minimum income to function as free and choosing agents. The basic means of survival are necessary to make use of our liberty, to have some autonomy, to function as effective citizens, to develop ethically, and to participate in civil society. These are conditions of adequate and educated inclusion in the market world of choice and trade.

A basic income would also reward otherwise unpaid work in care for the sick or elderly, which is often performed within families. A basic income would also encourage new entrepreneurs and creative artists. There would also be a huge saving in administration costs of often complex social security and welfare schemes. The level of the basic income does not have to be high. It can be set as a basic minimum for survival, thus retaining strong incentives for most people to seek additional sources of income.

Some forms of unconditional basic income have been pledged or introduced in several countries, including Brazil and Finland. Several developed countries have legal minimum income entitlements. In 1968, James Tobin, Paul A. Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith, and another twelve hundred economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce a system of income guarantees and supplements. Winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics who fully support a basic income include Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, James Meade, Herbert Simon, and Robert Solow. Significantly, this idea cuts across the political spectrum.

Conclusion

A key challenge for modern capitalist societies, alongside the needs to protect the natural environment and enhance the quality of life, is to retain the dynamic of innovation and investment while ensuring that the rewards of the global system are not returned largely to the richer owners of capital. As Paine put it in 1797:

All accumulation, therefore, of personal property, beyond what a man’s own hands produce, is derived to him by living in society; and he owes on every principle of justice, of gratitude, and of civilization, a part of that accumulation from whence the whole came.

But the benefits of ‘living in society’ are not simply through the advantages of cooperation or the division of labour. Modern societies have developed complex institutions that have empowered innovations and massive expansions of wealth. The ultimate and indivisible accumulation is not simply of things, but of knowledge, relations and rules, guarded by law within an adaptable and pluralist polity.

We need to update Paine’s approach to dealing with inequality, to suit modern times.

30 July 2016

Edited 31 July 2016

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

Bibliography

Ackerman, Bruce and Alstott, Anne (1999) The Stakeholder Society (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press).

Atkinson, Anthony B. (2015) Inequality: What Can Be Done? (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Herbert (1999) Recasting Egalitarianism: New Rules for Markets, States, and Communities (London: Verso).

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Herbert (2002) ‘The Inheritance of Inequality’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), Summer, pp. 3-30.

Claeys, Gregory (1989) Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (London and New York: Routledge).

Credit Suisse Research Institute (2012) Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2012 (Zurich: Credit Suisse Research Institute).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Paine, Thomas (1797) Agrarian Justice: Opposed to Agrarian Law and to Agrarian Monopoly (Philadelphia: Folwell).

Paine, Thomas (1945) The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, edited and introduced by Philip S. Foner (New York: Citadel Press).

Piketty, Thomas (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press).

Robinson, Andrew M. and Zhang, Hao (2005) ‘Employee Share Ownership: Safeguarding Investments in Human Capital’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43(3), September, pp. 469-88.

Wilkinson, Richard and Pickett, Kate (2009) The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (London: Allen Lane).

Posted in Common ownership, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Right politics, Socialism, Uncategorized

July 23rd, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

A Worker Cooperative in New York City

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

‘The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works … Nor is the question before us whether the market is a force for good or ill. Its power to generate wealth and expand freedom is unmatched.’

Barack Obama, 2009.

Politicians engage in slogans and sound-bites, but sometimes they reveal their true aims.

The Labour Party is now immersed in a battle for its leadership, and possibly for its survival as a viable political party. Jeremy Corbyn, overwhelmingly elected as leader in 2015 by about sixty per cent of the party membership, has lost the confidence of about eighty per cent of the party’s MPs.

Owen Smith

Owen Smith, Corbyn’s challenger for the Labour leadership, once worked for the private, research-based, pharmaceutical company Pfizer. In response, Corbyn and his allies have been quick to condemn Smith’s association with private enterprise.

Corbyn has always been a supporter of the original version of Labour’s Clause Four, with its aim of ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’. But since he became Labour Leader, he has kept this long-term aim mostly under wraps, highlighting his opposition to austerity economics instead.

However, on 21 July 2016, we had a brief peep under the tarpaulin, showing us Corbyn’s real aims.

Corbyn’s opposition to privately-funded pharmaceutical research

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) – the trade association for over 120 UK companies producing prescription medicines – quickly responded with a statement questioning Corbyn’s judgement in this area.

The ABPI pointed out that the pharmaceutical industry invests more than £88bn a year into research and development for new medicines and vaccines to help fight disease. In the UK this equates to £4.1bn per year of investment in R&D, with the Medical Research Council contributing £770m and research charities £1.3bn.

The pharmaceutical industry is global, and it is difficult to see how the taxpayer-funded UK Medical Research Council could take over the roles of the large private players in this sphere, unless this research was dramatically diminished. As the ABPI pointed out, research in this area has to be a collaboration between industry researchers, academics and clinicians, involving both public and private institutions.

Many successes in the development of drug treatments – including for breast cancer and HIV – have involved collaborations between research-oriented universities, risk-taking companies, concerned charities, government agencies, and so on. Typically these collaborations involve complex synergies and are international in scope.

Corbyn’s proposal that modern levels of pharmaceutical research should be publicly rather than privately funded – within one country – is feasible in neither budgetary nor practical terms.2

But further, in his zeal for the public takeover of research and development, Corbyn has failed to learn one of the crucial economic lessons of the twentieth century, concerning the limitations of largely publicly-owned R&D and need more broadly for a healthy, innovative, private sector.

This lesson is sketched out later below. It concerns the vital role of different forms of private enterprise – from corporations to worker cooperatives, which all have legal autonomy and they sell their products on a market. But first we emphasise that the essential role of the state and the public sector.

The state and the public sector are vital

We should also understand the vital role of the public sector in modern capitalist economists, including in the sphere of research. Numerous authors, including Richard Nelson, Ha-Joon Chang, Erik Reinert, Mariana Mazzucato and myself, have argued that – for several reasons – the state plays an essential, supportive role within modern capitalism.

In practical terms, evidence shows that the most successful economies are those that involve a collaboration of public and private institutions, including for research, development and innovation.

In practical terms, evidence shows that the most successful economies are those that involve a collaboration of public and private institutions, including for research, development and innovation.

For example, the modern patent system is backed up by legal and state powers that protect innovations from plagiarism and provide incentives for private research and creativity. It is an example of the way in which the state can maintain institutions that encourage private research.

There are areas where private enterprise works best, and there are areas where the public sector can be usefully involved. Determining these best areas in each case, is a practical question, involving detailed, complex, ongoing, empirical examination and experimentation.

Instead, Corbyn resorts to ideology, with this prescription: public ownership works best, and even when in doubt, nationalize. This is the mirror image of free-market ideologists, who stipulate: markets work best, and even when in doubt, privatize.

A simplistic ideological debate between private and public ownership dominated the twentieth century. The ‘common ownership’ version of Labour’s Clause Four, which lasted from 1918 to 1995, expressed one side in the debate. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, among many others, took the other side.

A key lesson of the twentieth century is that the dichotomy between public and private provision is misleading. The key question is how they can be usefully combined. Within any useful combination, both private and public enterprise have a crucial role to play. This essay explains why a private sector is vital.

My recent book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism explains why the role of the state is also crucial, even to sustain the institutions that make private enterprise work. But here I concentrate on the case for private enterprise.

The failure of centrally-planned innovation

Any vision of a large-scale planned economy involves assembling information in local or national agencies, and then making decisions based on this information. Proposed innovations and other changes must be appraised, and decisions on their viability must be made.

In their schemes to bring all knowledge together into the hands of planners, advocates of comprehensive planning overlook the time and other difficulties involved in gathering and dealing with available information. Also they give inadequate consideration to how innovations are to be incentivized, tested and promoted.

Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority.

Innovation depends on hunches about the future. Successful innovation takes into account local, tacit and other knowledge concerning circumstances and possibilities. Much of this knowledge involves complex details and contexts, and cannot all be brought together and utilized by a central committee or planning authority.

Because of diminished competitive pressures, nationalized industries in centrally planned economies, such as the Soviet Union and Mao’s China, have been unimpressive in terms of innovation and flexibility. Why should a committee back innovation or change, especially when it carries risks of failure? Why should they risk their jobs when they have no secure right of additional reward in the case of success?

The economist Peter Murrell showed empirically that the former Communist countries were apparently no less efficient in allocating resources than capitalist economies. Where they lagged was in terms of dynamic efficiency: the ability to innovate. This shortfall is endemic to any system that works on the basis of hierarchical planning, rather than independent enterprise with legal rights to reap and retain rewards.

Whatever the limitations of a market system, it has the advantage that it does not require majority agreement before a decision can be made to produce or distribute a good or service. Private property and contracts permit zones of autonomy within an interrelated system; agents may reach decisions through negotiated contracts with others. The costs and benefits are devolved to individuals or firms.

Through private enterprise it is possible for many technological or institutional innovations to be pioneered without the prior agreement of (democratic) committees or (undemocratic) bureaucrats. This analysis is borne out by experience. The former Soviet-type economies in Russia and China lacked devolved autonomy, secured by private ownership.

Eventually they learned that lesson. The change in China was most dramatic. After the Communist Revolution of 1949, agriculture in China was organized into large collective farms. Other than by threats and bureaucratic bullying, farmers had little incentive to improve productivity. Risky innovation was unwise. Productivity remained low and often there were shortages of food. But Mao Zedong died in 1976, opening up the possibility of reform.

In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.

In 1978 some Chinese peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate. After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty.

China’s spectacular economic growth began when agriculture began to pass into the private control of the peasants after 1978. The Chinese Communist Party endorsed these changes in the rights to use and manage land (while keeping legal title to the land in the hands of the collectives), and also promoted private businesses in rural areas.

China also retained many state-owned enterprises. The state continued to play a major strategic role in economic development. China has demonstrated how viable public and private sectors are essential for growth and innovation in a modern large-scale economy.

The failure of classic socialism

Some version of socialism might work on a small scale. Cooperation can work in this context, based on close, inter-personal interactions. Humans have co-operated in this way, in families and tribal groups, for many thousands of years.

Elinor Ostrom

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Their small size allows participants to monitor each other, to ensure that necessary tasks are carried out and that the interests of the community are served.

Enforcement mechanisms range from praise to punishment. Within these relatively small and cohesive groups, trust and targeted sanctions are mechanisms for encouraging cooperation, reciprocity and compliance with customary rules.

But socialism on a small scale would lack the economies of large-scale production and the technological dynamism of today’s competitive capitalism. Modern medicines and technologically-advanced treatments, requiring extensive funding, risk-taking and research collaboration, could not be developed. With inferior drugs and healthcare, human longevity would be lower than it is today.

In larger socialist societies, individual incentives for effort and innovation are diminished, and compensatory, face-to-face, trust-based mechanisms to sustain cooperation are relatively less effective. When we move from communities of a hundred or so, where it is possible for everyone to know everyone else, to communities of thousands or more, then interpersonal trust and reputation are much less effective at the overall level, and they have to be supplement both other incentives and constraints.

When thousands of people are brought together, and rewards are shared, then there is less incentive to make the extra effort, because the rewards from that additional work would be hugely diluted.

Large private corporations face this problem too. But competitive pressure on the private corporation obliges it to incentivise its workforce in some way, so that most employees pull their weight.

Market competition is absent or much diminished in a centrally planned economy. Instead, the pressure to perform comes from the state. Consequently, strong discipline is necessary to sustain production, and larger-scale socialism engenders authoritarianism and bureaucracy. Twentieth-century evidence strongly supports this analysis.

Those that propose ‘democratic socialism’ in large-scale societies fail to address some key practical questions. How is all the important information to be gathered and transmitted? How are resources to be produced and distributed? How is everyone to be incentivized to work well and to innovate? And if the system is to be ‘democratic’, how would it be possible for everyone involved to vote on every important decision?

Robert Owen

Such practical considerations show that democratic socialism (at least in the classic sense of Robert Owen and Karl Marx, who proposed common ownership and the abolition of private enterprise) is unfeasible in any large-scale complex economy.

While interpersonal interactions can engender cooperation on a small scale, in large-scale societies other mechanisms and incentives are necessary. For dynamism and efficiency, there have to be competition, markets and a large private sector, as well as a state.

Private ownership is also important for political reasons, to create zones of politico-economic power that can countervail state autocracy.

Contrary to the twin, all-or-nothing, ideologies of classical socialism and free-market purism, this leaves open a huge area for economic reform and development. A private sector can be made up of many different kinds of enterprise, including worker cooperatives and social enterprises, as well as more conventional corporations. The state can intervene in a myriad of ways, including the adoption of redistributive taxation and the development of a strong welfare state.

Once all this is understood, then the game changes – irrevocably. Once it is realized that classical socialism cannot work (at least in a humane way) then you have to look for alternatives. Once it is acknowledged that private property and markets are indispensable in large-scale modern economies, then you have to accept them, warts and all. The best that can be done is to minimize their deleterious effects, and to explore viable avenues of institutional reform.

Much of the Labour Party learned this lesson in the era from 1945 to 2015. It adjusted to the mixed economy and began to understand the virtues and indispensability of private enterprise. That lesson seems to be forgotten by a large number of Labour Party members, who continue to support Corbyn and his naïve, outdated ideology. Unless that lesson is learned again, and quickly, then Labour has no future as an electable political party.

23 July 2016

Edited 24 July 2016

|

My forthcoming book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

To be published by University of Chicago Press in November 2017

|

-

Corbyn added that he was in favour of a National Health Service that is ‘totally public’ with ‘publicly employed people running it’. Is he aware that GPs are not NHS employees but self-employed contractors? If so, is it his intention to make all GPs employees?

-

In an interview on 24 July 2016, Corbyn’s ally John McDonnell backtracked on his leader’s statement, re-admitting a role for private sector pharmaceutical research under some vague notion of ‘democratic control’. He said that Corbyn’s statement had been ‘misinterpreted’. But this dishonest manoeuvring under pressure fails to mask their true aims.

Bibliography

Chang, Ha-Joon (2002) Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective (Anthem Press: London).

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1944) The Road to Serfdom (London: George Routledge).

Mazzucato, Mariana (2013) The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (London and New York: Anthem).

Murrell, Peter (1991) ‘Can Neoclassical Economics Underpin the Reform of Centrally Planned Economies?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(4), Fall, pp. 59-76.

Nelson, Richard R. (1981) ‘Assessing Private Enterprise: An Exegesis of Tangled Doctrine’, Bell Journal of Economics, 12(1), pp. 93-111.

Nelson, Richard R. (2003) ‘On the Complexities and Limits of Market Organization’, Review of International Political Economy, 10(4), November, pp. 697-710.

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Reinert, Erik S. (2007) How Rich Countries Got Rich … And Why Poor Countries Stay Poor (London: Constable).

Zhou, Kate Xiao (1996) How the Farmers Changed China (Boulder, CO: Westview Press)

Posted in Common ownership, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Right politics, Robert Owen, Socialism, Uncategorized

June 5th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The terms Left and Right have become ambiguous and self-contradictory. Today the term ‘right-wing’ is applied to diverse and opposed views such as the following:

♦ Those who favour private ownership and markets are often placed on the political Right, including those who are strong supporters of democracy and human rights.

♦ Those who put private property above everything, and care less about democracy, are also described as Right.

♦ Pro-market libertarians, who are so strongly against states that they oppose wars, are also described as Right.

♦ Nationalists that venerate the national state are also described as Right, even if they support democracy and individual rights.

♦ Fascists and racists are also seen as Right, including those who would pursue wars and would limit individual freedoms or rights

Hence the debased term Right now covers democrats and despots, peace-mongers and war-mongers, nationalists and individualists, and defenders and opponents of human rights. There is nothing about private ownership and markets that necessarily implies racism or belligerent nationalism. Yet these different things are conflated under the same label.

The word Left has also slipped into various contradictory usages:

♦ Advocates of substantial state intervention in the economy, typically with some planning and nationalized enterprises, are described as Left.

♦ Advocates of a minimal state, with autonomous communes instead of nationalized industry, are also described as Left.

♦ People who care less about democracy or liberty, and much more about public ownership, national planning or the abolition of poverty, are often described as Left.

♦ Champions of extended democracy, decentralization, popular sovereignty, individual liberty and freedom of expression are often described as Left.

Accordingly, the term Left is now applied to both statist centralizers and communitarian decentralizers, to both totalitarians and ultra-democrats, and to both minimizers and maximizers of liberty.

Both the Left and the Right have advocated forms of collectivism. The word fascism derives from its symbolic use of the fasces of Ancient Rome, with rods bound together to signify collective strength. Fascism subjected individualism to the collective whole. Similarly, nationalism extols the nation over the individual. If you insist that collectivism is Left, be warned that fascism and nationalism also incline in the same collectivist direction.

Both the Left and the Right have advocated forms of collectivism. The word fascism derives from its symbolic use of the fasces of Ancient Rome, with rods bound together to signify collective strength. Fascism subjected individualism to the collective whole. Similarly, nationalism extols the nation over the individual. If you insist that collectivism is Left, be warned that fascism and nationalism also incline in the same collectivist direction.

Also, as shown below, both the Left and the Right have been aligned with forms of individualism and private property. These terms have become confused and unclear.

The original Left

The origins of the political terms Left and Right are in the French Revolution. In 1789, in the National Constituent Assembly, those deputies most critical of the monarchy began to congregate on the seats to the left of the President’s chair. Conservative supporters of the aristocracy and the monarchy would congregate on the right side of the Assembly. The Baron de Gauville explained:

The origins of the political terms Left and Right are in the French Revolution. In 1789, in the National Constituent Assembly, those deputies most critical of the monarchy began to congregate on the seats to the left of the President’s chair. Conservative supporters of the aristocracy and the monarchy would congregate on the right side of the Assembly. The Baron de Gauville explained:

‘We began to recognize each other: those who were loyal to religion and the king took up positions to the right of the chair so as to avoid the shouts, oaths, and indecencies that enjoyed free rein in the opposing camp.’

Those seated to the left of the Constituent Assembly wished to limit the powers of the monarchy, and eventually to create a democratic republic.

Those on the right wished to maintain the authority of the Crown by means of a royal veto, to preserve some rights of the aristocracy, to have an unelected upper house, and to maintain major property and tax qualifications for voting.

By contrast, the Left demanded an end to aristocratic privileges, limitations to the power and privileges of the church, a single-chamber legislature in which all power rested with democratically elected representatives, and a broad popular – but wholly male – franchise.

In 1789, Jacobin Clubs sprung up all over France. Originally the Jacobin Clubs were an inclusive forum for all revolutionaries; people later described as Girondins and Montagnards were among their number.

In 1789, Jacobin Clubs sprung up all over France. Originally the Jacobin Clubs were an inclusive forum for all revolutionaries; people later described as Girondins and Montagnards were among their number.

The Girondins acquired that name because a number of them came from the départment of the Gironde. The Montagnards were a radical faction within the Jacobins: they took their name from their occupation of the higher seats behind the President of the Assembly.

By 1791 the Jacobin Clubs were dominated by Girondin intellectuals and orators. Hence Girondins such as Jacques-Pierre Brissot and Thomas Paine were also Jacobins.

At least from 1789 to 1792, when the label was most inclusive, the Jacobins as a whole were the Left. Like other radical Enlightenment thinkers, they believed that ideal governments were founded on natural rights and by the will of the people, rather than on religion or tradition.

Accordingly, the Left and Right divided on the question of the legitimate source of authority for government, and on the question of universal and equal human rights. To be Left was to reject aristocracy or religion as sources of authority, and instead claim authority in the will of the people.