Category: Nationalization

May 21st, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Although the two biggest UK political parties are very different in important respects, Labour under Jeremy Corbyn and the Conservatives under Theresa May have each converged on different forms of pro-Brexit, economic nationalism.

Economic nationalism prioritises national and statist solutions to economic problems. Although it does not shun them completely, it places less stress on global markets, international cooperation and the international mobility of capital or labour. It believes that the solutions to major economic, political and social problems lie within the competence of the national state.

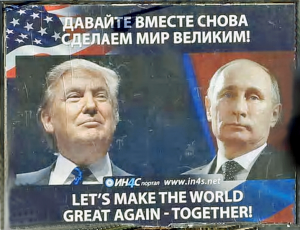

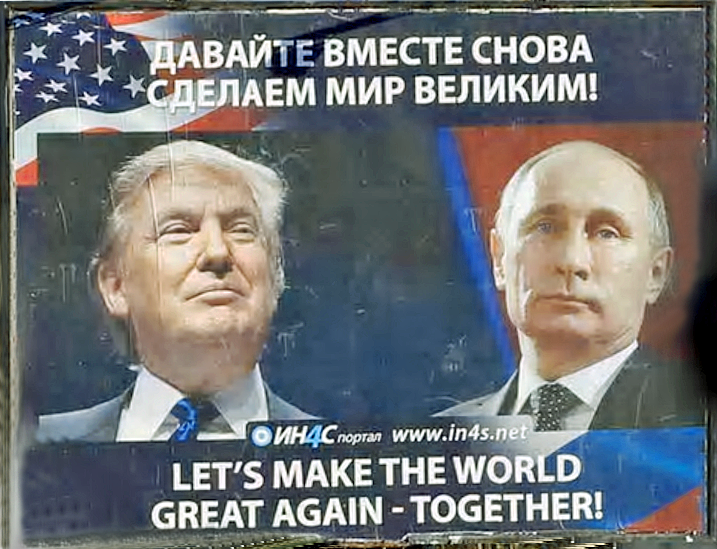

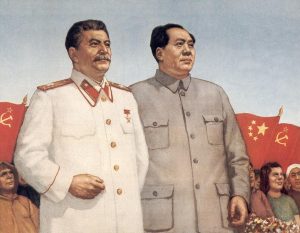

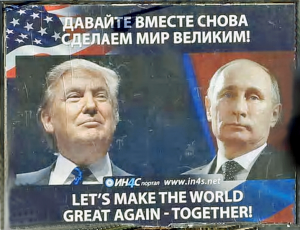

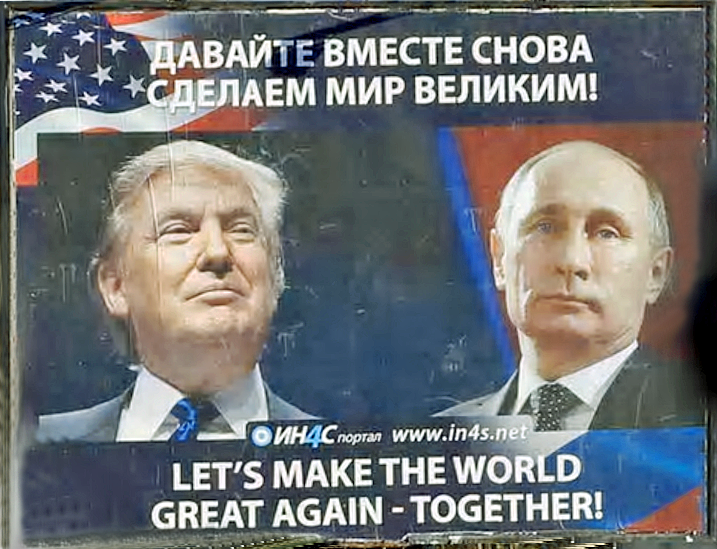

Other countries have turned in the same direction, including the United States under Donald Trump and Russia under Vladimir Putin. Previously, both Soviet-style and fascist economies have embraced economic nationalism. China has continued along this road, even after its acceptance of private enterprise and a market economy.

Other countries have turned in the same direction, including the United States under Donald Trump and Russia under Vladimir Putin. Previously, both Soviet-style and fascist economies have embraced economic nationalism. China has continued along this road, even after its acceptance of private enterprise and a market economy.

Economic nationalism has been used successfully as a tool of economic development, by creating a state apparatus to build an institutional infrastructure and mobilise resources. But it brings severe dangers as well as some advantages. Its reliance on nationalist rhetoric can feed intolerance, racism and extremism.

Furthermore, as it concentrates economic and political power in the hands of the state, economic nationalism undermines vital checks and balances in the politico-economic architecture.

As numerous social scientists (from Barrington Moore to Douglass North) have shown, democracy and human rights cannot be safeguarded without a separation of powers, backed by powerful countervailing politico-economic forces that keep the state in check.

From Thatcherism to Mayhem: Tory economic nationalism

Margaret Thatcher

In the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher changed the Tory party from a paternalist party of the elite to a more radical, free-market and individualist force, embracing the ideologies of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

A logical consequence of this market fundamentalism was to embrace the European Single Market, which her successor John Major did in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. But this was too much for the Tory nationalists, who were already turning against the European Union and all its works.

The tension grew within the Tories between those that pursued international markets in the name of market fundamentalism, and those who worried that global trade and the free movement of labour were undermining the powers of the British nation state.

A compromise option – widely touted during the June 2016 EU referendum – was to exit the EU but remain in the single market. But a major implication of this was that the free movement of labour to and from the EU would have to be retained. May became prime minister and declared that Britain would leave the single market as well as the EU.

This marks a major ideological shift within the Conservative Party. The pursuit of free markets, promoted so zealously by Thatcher, has moved down the Tory agenda, in favour of nationalism, increased state control, reduced parliamentary scrutiny, and lower immigration, whatever the economic costs.

Forward together: the new-old Toryism

This shift is signalled by a remarkable passage in the 2017 Conservative general election manifesto:

“We do not believe in untrammelled free markets. We reject the cult of selfish individualism.”

This could be interpreted as a cynical attempt to attract some Labour voters. Probably, in part, it is. But there is much more to it than that. It shows how all the whingeing about “neoliberalism” is now outdated and much off the mark.

Crucially, the Tory Party was traditionally opposed to “untrammelled free markets” and it worried about the destructive and corrosive effects of individualism and greed.

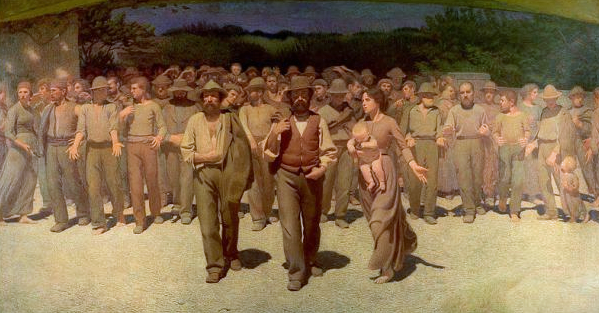

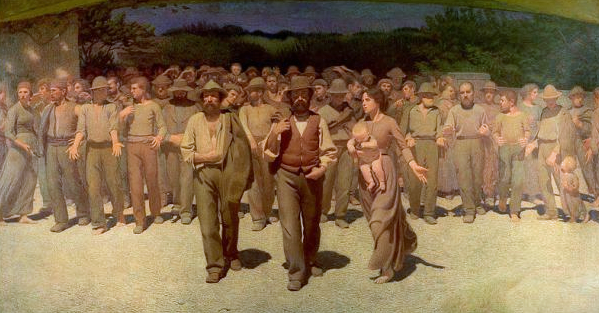

As Karl Polanyi pointed out in his classic book on The Great Transformation, the first fighters for factory and employment legislation, to protect workers from the results of reckless industrialization in the 1830s and 1840s, were from the ranks of the church and the Tory Party:

“The Ten Hours Bill of 1847, which Karl Marx hailed as the first victory of socialism, was the work of enlightened reactionaries.”1

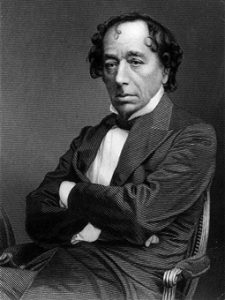

Benjamin Disraeli

Tories like Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, were great nineteenth-century social reformers. The Tory Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli railed against selfish individualism, particularly in his novels. For Disraeli, British imperialism was more important than unalloyed individualism.

May has brought the Tory party back to its pre-Thatcher roots. But, less enlightened than Shaftesbury or Disraeli, she has little appetite for protective legislation or constitutional reform. Instead, she celebrates her own powers of leadership and seeks a mandate to concentrate power in her hands.

She has little enthusiasm for democracy either. If it were not for the heroic efforts of Gina Miller and the decision of the Supreme Court, the triggering of Article 50 – to start the process of leaving the European Union – would have been taken by the executive without a parliamentary vote.

The 2017 Tory manifesto is a maypole for nationalism. “Britain” is one of its most-used words. It says that immigration will be brought down, while existing powers by the British state to read emails and monitor your activity on the web will be increased. She will create an Internet that is controlled by the state. May is developing the infrastructure of an authoritarian nationalist regime.

Bringing the state back in: Labour’s new-old economic nationalism

At least on the surface, there are dramatic differences with Labour’s manifesto, which, for example, contains more measures targeted at the poor and elderly. Labour also gives much more verbal emphasis to human rights and democracy.

But at the core of Labour’s 2017 manifesto is a strong dose of economic nationalism, with Labour’s greatest commitment to public ownership since the “suicide note” manifesto of 1983. There are plans to bring the railways, energy, water and the Royal Mail all back into public ownership.

The 2017 manifesto declares: “Many basic goods and services have been taken out of democratic control through privatization.” But there is little explanation of what “democratic control” would mean under public ownership.

How would it work? Would parliament take decisions on everything? In reality these proposals – whatever their other merits – would enlarge state bureaucracy: there is no explanation how they would extend democracy.

The words “control” or “controls” appear 32 times in the 2017 manifesto. There is insignificant explanation of how “controls” work. The Labour manifesto envisions a concentration of economic power in the hands of the state, notwithstanding its verbal commitment to regional and local, as well as national, public management.

While there are commendable measures to enhance and enlarge an autonomous sector of worker-owned enterprises, there is little recognition of the importance of having a viable and dynamic private sector as well.

Corbyn’s Labour: forward to the past

As May has brought the Tories back to the pre-Thatcher years, Corbyn has brought Labour back to its traditional roots, before the leadership of Tony Blair.

With his 1995 changes to Clause Four of the Labour Party Constitution, Blair brought in an explicit commitment to a dynamic private sector. Labour stood for an economy where “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation”. Corbyn has returned to the spirit of Labour pre-1995 constitution, even if he has not yet changed the wording.

With his 1995 changes to Clause Four of the Labour Party Constitution, Blair brought in an explicit commitment to a dynamic private sector. Labour stood for an economy where “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation”. Corbyn has returned to the spirit of Labour pre-1995 constitution, even if he has not yet changed the wording.

Corbyn has proposed that Britain can be “better off” outside the EU. He argued that EU rules block the kind of state-heavy industrial policy that he favours. But EU countries such as France and Germany already have strong interventionist policies for industrial and infrastructural development. In truth, Corbyn favours repeated doses of statist socialism in one country.

With some Stalinist exceptions in his coterie, Corbyn and his followers are mostly sincere in their commitment to democracy and human rights. But what they do not understand is that their proposed statist concentration of economic power will undermine countervailing politico-economic forces that can help to keep the state leviathan in check.

Jeremy Corbyn and Hugo Chávez

These countervailing and separated powers are vital. Especially in times of hardship or crisis, there will be a temptation by some in power (at the local or national level) to abuse rights and undermine democracy. Every single historical case shows this result.

Attempts “to take control of the economy”, even with measures of decentralization and local power, have led to restrictions on press freedom, arbitrary detentions, abuses of human rights, and even famine.

Forward together: economic nationalists take the helm

Further doses of economic nationalism may be possible in a country as large as the United States. In 2015, exports from the USA amount to about 13 per cent of GDP. Hence economic nationalists in the USA can reduce trade without too much contraction of the economy. It may turn further inwards, cut imports and still survive a loss of exports.

But the UK has become a globally-orientated, open economy, exporting 28 per cent of its GDP in 2015. About 45 per cent of these exports go to the European Union.

By exiting the EU Single Market, and by walking away from EU trade deals with non-EU countries that benefit EU member states, Labour and the Tories would threaten the UK economy with a massive downturn. The British economy would fall off a cliff.

By exiting the EU Single Market, and by walking away from EU trade deals with non-EU countries that benefit EU member states, Labour and the Tories would threaten the UK economy with a massive downturn. The British economy would fall off a cliff.

In this crisis, rightist economic nationalists will blame foreigners and immigrants, and leftist economic nationalists will blame the rich.

It will be “the few” – designated by their ethnicity or by their assets – who will get the blame. Their rights will be under threat, as so will the liberties of all of us. Whatever variety is chosen, economic nationalism could severely undermine the viability of democracy in the UK.

21 May 2017

Minor edits – 23, 28 May, 29 June

|

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

Endnote

Bibliography

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Moore, Barrington, Jr (1966) Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World (London: Allen Lane).

North, Douglass C., Wallis, John Joseph and Weingast, Barry R. (2009) Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press).

Polanyi, Karl (1944) The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (New York: Rinehart). See esp. pp. 165-66.

Posted in Brexit, Common ownership, Democracy, Donald Trump, Immigration, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Populism, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Tony Blair, Tony Blair, Uncategorized, Venezuela

May 8th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

This is in part a personal memoir – concerning my role in a minor episode in political history. More importantly, it has lessons concerning Labour’s ideological inertia – the difficulty of modernising the party and bringing it from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century.

Socialism and Labour’s Clause Four

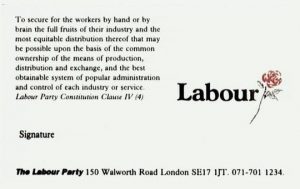

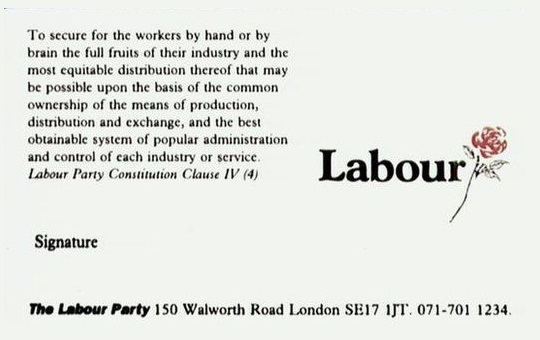

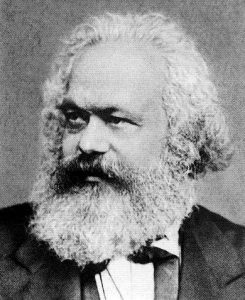

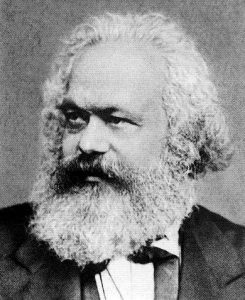

Both Robert Owen and Karl Marx defined socialism as “the abolition of private property”. This kind of collectivist thinking was encapsulated in Clause Four, Part Four of the Labour Party Constitution when it was adopted in 1918:

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector. Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

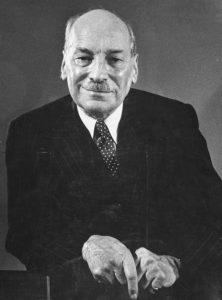

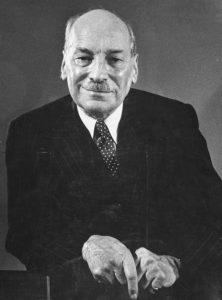

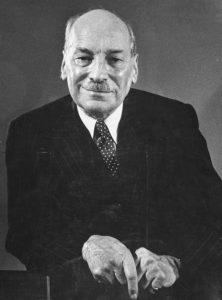

Clement Attlee

In 1937, eight years before he became Prime Minister, Clement Attlee approvingly quoted the words of Bertrand Russell: “Socialism means the common ownership of land and capital together with a democratic form of government. … It involves the abolition of all unearned wealth and of all private control over the means of livelihood of the workers.”

After 1945, the position of many leading Labour Party members began to shift. First the realities of gaining and holding on to power – as a majority party for the first time – dramatized the political and practical unfeasibility of abolishing all private enterprise. Some nationalization was achieved, but a large private sector remained.

In 1956 C. Anthony Crosland published The Future of Socialism. This sought a reconciliation with markets, private enterprise and a mixed economy. In 1959 the (West) German Social Democratic Party abandoned the goal of widespread common ownership. In the same year, Hugh Gaitskell tried to get the British Labour Party to follow this lead, but met stiff resistance. Clause Four remained intact.

Richard Toye noted that the Labour Party assumed widespread public ownership and failed to develop adequate policies concerning the private sector:

“Labour, until at least the 1950s, showed little interest in developing policies for the private sector. During the 1960s, the party demonstrated continuing ambiguity about whether or not competition was a good thing. This ambiguity continued at least until the 1980s.”

The Thatcher Revolution

There were Labour governments from 1964 to 1970 and from 1974 to 1979. But then Margaret Thatcher came to power.

After this defeat, Labour’s instinct was to turn to the left, in the belief that it could have held onto power if it had held to classical socialist principles. Michael Foot was elected as leader, and Dennis Healey narrowly defeated Tony Benn for the position of deputy leader.

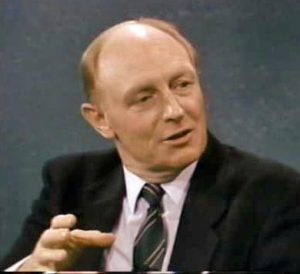

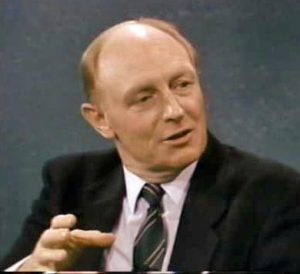

Neil Kinnock

Despite a severe recession with millions unemployed, following the implementation of monetarist austerity policies, Labour suffered a massive defeat in the 1983 general election. Labour’s share of the vote fell below 28 per cent – the party’s lowest figure since 1918. Michael Foot resigned as leader and Neil Kinnock took his place.

Thatcher had boosted her popularity due the Falklands War. One of Thatcher’s most popular domestic policies was to promote the sale of council-owned housing to the tenants. Labour had opposed this policy. The 1983 defeat prompted a rethink, on this and other issues.

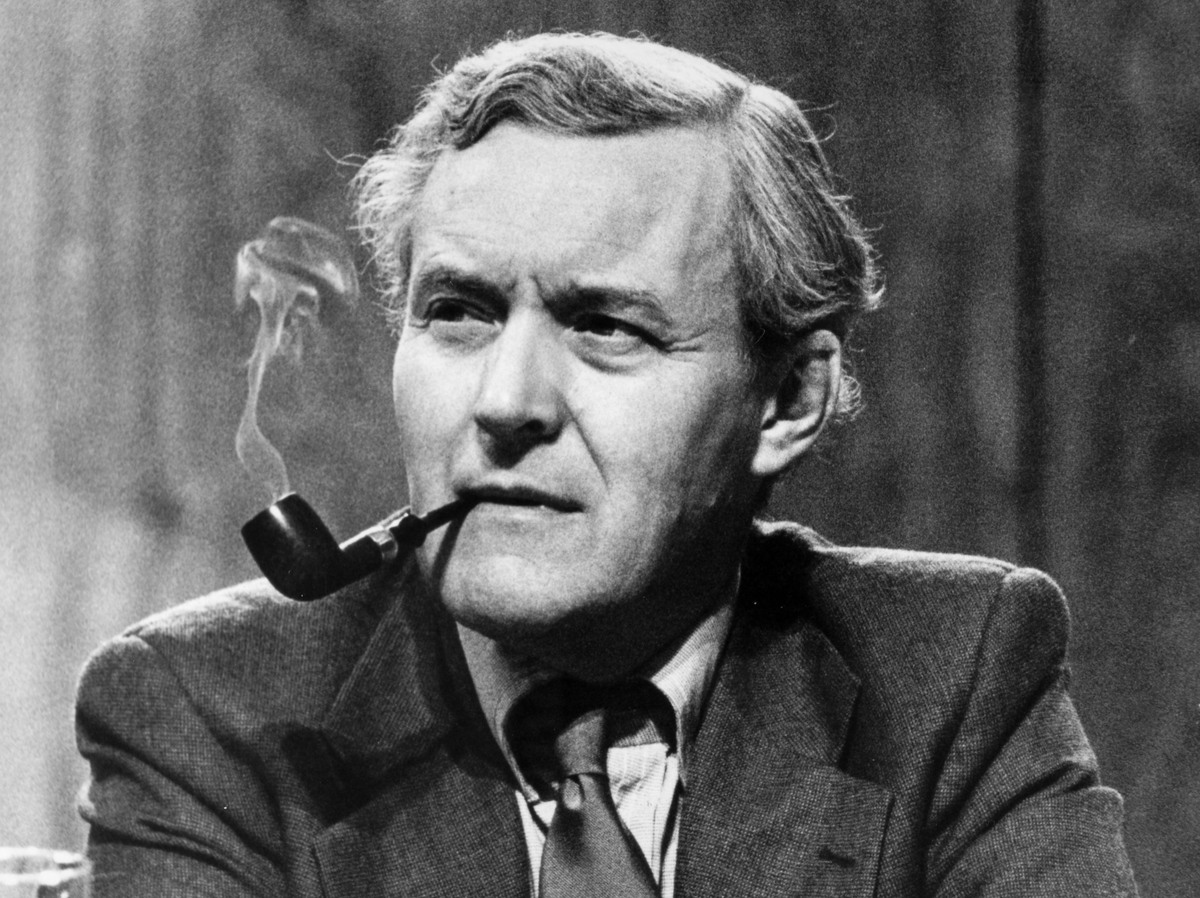

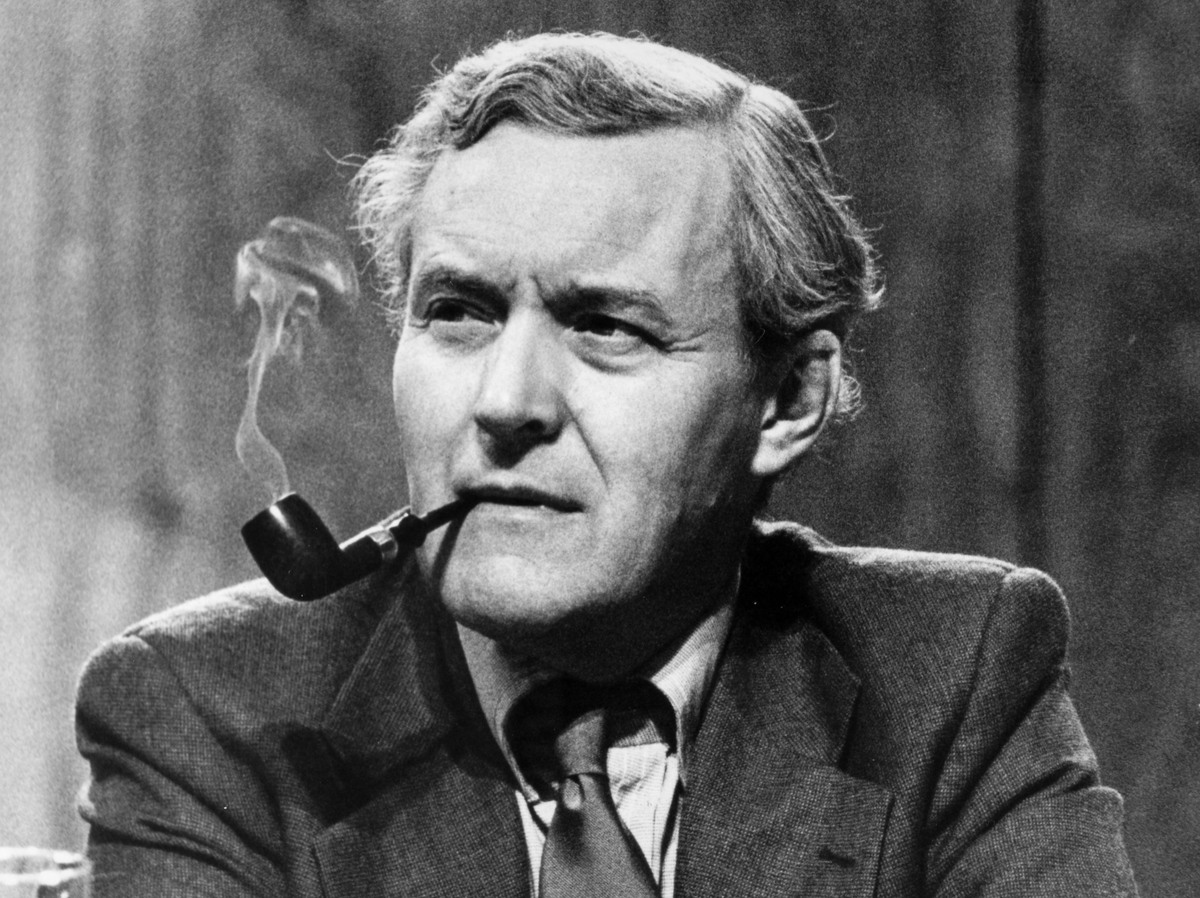

Tony Benn

For some of us, this rethink amounted to more than expedient doctrinal trimming. Encouraging home ownership was really a good idea: why should all property be owned by the rich? But while supporting home ownership, we argued that the government should also build more social housing and enlarge the stock available for rent by low-income families.

But these ideas met stiff resistance in the Labour Party ranks, and not simply from Trotskyist entryists such as Militant. The resistance from Tony Benn and his supporters was substantial and even more enduring. It was clear that old-fashioned socialist ideas still had a tenacious appeal for Labour’s membership.

The Labour Coordinating Committee

The Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) became one of the primary modernising forces within Labour. Its leadership included Hilary Benn, Cherie Blair, Mike Gapes, Peter Hain, Harriet Harman and others of enduring fame. I was elected to its executive committee. We worked closely with Kinnock and members of his shadow cabinet, including Robin Cook.

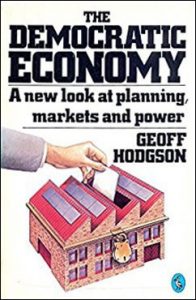

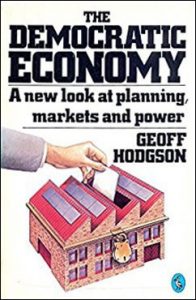

I had written a book entitled The Democratic Economy where I argued that socialists should support a permanent private sector in the economy. The book was published by Penguin in 1984. Another influential work at the time was Alec Nove’s Economics of Feasible Socialism, which also argued for a substantial role for markets.

I had written a book entitled The Democratic Economy where I argued that socialists should support a permanent private sector in the economy. The book was published by Penguin in 1984. Another influential work at the time was Alec Nove’s Economics of Feasible Socialism, which also argued for a substantial role for markets.

On 26 November 1983, at the Labour Coordinating Committee AGM in Birmingham, I proposed that Clause Four of the Labour Party constitution should be rewritten to include an acceptance of a private sector and a role for markets. But I was defeated over the idea that Clause Four should be rewritten. This was out of fear of antagonising the Benn wing. Instead, the LCC resolved that Clause Four should be “clarified”.

But a resolution on long-term aims, which I had helped to draft, was passed by a large majority. The resolution called for the Labour Party to draft a new statement of aims, upholding “that socialism involves extended democracy and real equality. Democracy under socialism is extended to industry and the community … and must involve a substantial decentralisation of power.”

Equality meant the “absence of discrimination on the basis of gender and race, universal freedom from poverty, and a widespread distribution of wealth and power, as well as formal equality under the law and universal suffrage.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

There was also a “commitment to internationalism, disarmament and peace” and “a disengagement from the power blocs” of the West and East.

I think that today Jeremy Corbyn and his followers would accept much or all of this, at least as a temporary stopping-point on the road to full socialism. But in the 1980s there was strong hostility to these revisionist ideas from within Labour’s ranks at the time, including from Corbyn and Tony Benn.

Since then my own views have adjusted. See my Wrong Turnings book. But this blog is not primarily about me. It is about what has happened to the Labour Party and how difficult it is to change its DNA.

For a while, the LCC tried to keep the conversation going on the need to revise Labour’s aims. The Guardian newspaper reported the LCC conference with the headline: “Labour breaks taboo on ownership”.

The LCC held a conference in Liverpool in June 1984 on “The Socialist Vision”. But enthusiasm for this discussion fizzled out. Many leaders of the LCC wanted a political career, and they wished to widen their support on constituency selection committees.

By 1985 the LCC’s revisionist initiative had been kicked into the long grass. My efforts to change Clause Four had failed.

From Kinnock to Blair

But to their credit, Neil Kinnock and his deputy Roy Hattersley saw the need for Labour to modernise its aims. I advised them both for a while. Another election defeat in 1987 spurred a rethink. But by then I had become inactive in the Labour Party.

As Richard Toye has recorded, in 1988 Kinnock and Hattersley presented a new document on “Aims and Values” to Labour’s National Executive Committee. But “it was criticised by John Smith, Bryan Gould and Robin Cook as being too enthusiastic about the benefits of the market, and was watered down accordingly”.

Tony Blair

Clearly, even after a third election defeat there was still strong resistance, from both the “soft” and the “hard left”, to the idea of embracing markets and private property.

After the next election defeat in 1992, Kinnock stood down. He was replaced by John Smith, who died tragically from a heart attack. Then Tony Blair became leader, with a firm resolve to modernize the party. Four election defeats had made the majority of members more receptive to his ideas.

Blair’s Revision of Clause Four

In 1995, after 77 years, Clause Four was changed. Tony Blair successfully ended the Labour Party’s longstanding constitutional commitment to far-reaching common ownership. Tony Benn protested: “Labour’s heart is being cut out”. The new wording of “Clause IV: Aims and Values” began as follows:

“The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few; where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe and where we live together freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.”

The 1918 formulation did not use the word socialism – it had common ownership instead. Ironically, Blair introduced the term in 1995. But he attempted to change its meaning. He promoted “social-ism”, which now meant recognizing individuals as socially interdependent. It also signalled social justice, cohesion and equality of opportunity.

The new Clause Four continued, to make a significant statement in support of competiive markets and a private sector. Labour now stood for:

“A DYNAMIC ECONOMY, serving the public interest, in which the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation to produce the wealth the nation needs and the opportunity for all to work and prosper with a thriving private sector and high-quality public services …”

The text went on to cover “a just society”, “an open democracy”, “a healthy environment” and “defence and security”.

John A Hobson

Labour’s new aims and values were indistinguishable from the earlier views of radical social liberals, such as T. H. Green, J. A. Hobson and David Lloyd George. And with its endorsement of “the rigour of competition” and “a thriving private sector” it was a hundred miles away from the collectivism of Robert Owen and other original socialists.

Instead of tackling the problem of its old collectivist DNA more directly, Blair tried to change the meaning of socialism and even rewrote parts of its own history. It is unsurprising that the old socialist DNA survived. It remained viable, partly because Labour still declared itself as socialist. Blair made radical changes but also gave succour to the traditional socialist wing of the party.

Blair’s popularity within the party had waned even before his decision in 2003 to support George W. Bush’s Iraq War. Much of this disenchantment was due to his abandonment of wholesale common ownership.

Blair had failed to develop a fully-fledged alternative vision within Labour to replace old-fashioned common ownership. He had made Labour implicitly embrace liberalism in doctrine. But this was unspoken, and masked by the explicit insertion of socialism in its aims. This inadvertently played into the hands of the party’s enduring, backward-looking left.

Labour’s Love Lost

Just as Labour had shifted to the left after losing power in 1979, after its 2010 defeat it shifted slightly leftwards under Ed Miliband. But the new leader had no clear alternative to the economics of austerity. So after another defeat in 2015. the party membership took a massive lunge to the left. It elected the Bennite, retro-Marxist, perennial protestor, Jeremy Corbyn.

But while old ideas within Labour had survived, the structure of the party and its electoral base had changed enormously in the period from 1983 to 2015. Kinnock had relied on the moderating force of the trade unions, to fight the hard left and move the party toward electability. But by 2015 the unions had been gravely weakened and several had moved toward the hard left.

But while old ideas within Labour had survived, the structure of the party and its electoral base had changed enormously in the period from 1983 to 2015. Kinnock had relied on the moderating force of the trade unions, to fight the hard left and move the party toward electability. But by 2015 the unions had been gravely weakened and several had moved toward the hard left.

In 1983, both the affiliated unions and the Labour MPs had a major role in the election of any new Labour leader. But by 2015 the power was almost entirely in the hands of the Labour Party membership, and the other moderating forces were much diminished.

Labour’s history shows how difficult it has been to change Labour’s old-fashioned socialist DNA. Those that put their faith in a revival of moderation within must take into account the near-collapse of those internal forces that brought the party back to sanity in 1951-1964 and in 1979-1997.

In 1983 there was still a strong, traditional, tribal, Labour vote, part of it based on surviving industries such as coal and steel. By 2015 the working class was much more fragmented, with skilled, aspirational cohorts at one extreme, and uneducated, demoralized, welfare dependents at the other.

The old tribalism was challenged by UKIP and by a revived working class Conservatism, playing the nationalist card. Labour’s potential electoral base has been transformed beyond recognition. The division of labour has become profoundly political, as well as enduringly economic.

Today, there seems little hope for a party that calls itself “Labour”, just as there is no future for a party that retains the word “socialism” or the goal of widespread public ownership. The socialist experiments of the twentieth century testify to their failure. Labour, in short, is an anachronism.

8 May 2017

|

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

References

Attlee, Clement R. (1937) The Labour Party in Perspective (London: Gollancz).

Blair, Tony (1994) Socialism, Fabian Pamphlet 565 (London: Fabian Society).

Clarke, Peter (1978) Liberals and Social Democrats (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1984) The Democratic Economy: A New Look at Planning, Markets and Power (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Nove, Alexander (1983) The Economics of Feasible Socialism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Toye, Richard (2004) ‘The Smallest Party in History’? New Labour in Historical Perspective’, Labour History Review, 69(1), April, pp. 83-104.

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Property, Robert Owen, Socialism, Tony Benn, Tony Blair, Tony Blair

February 21st, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

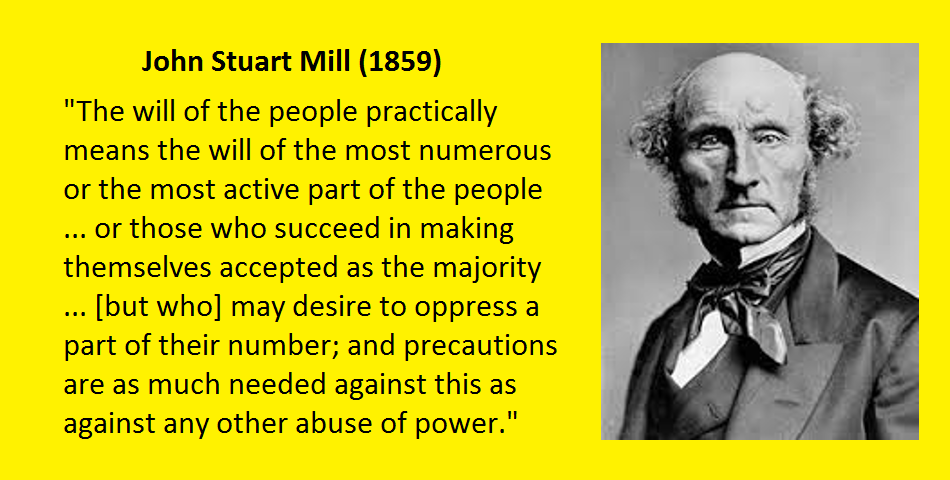

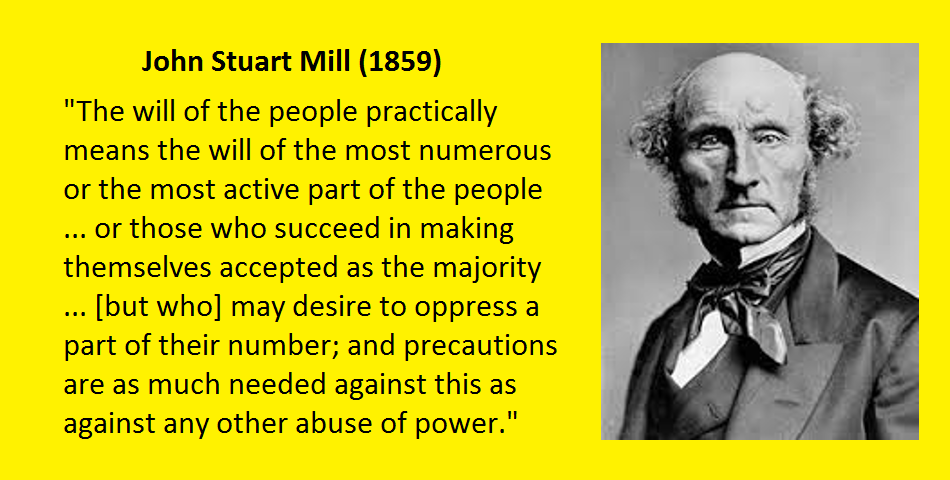

Despite her previous opposition to Brexit, Prime Minister Theresa May tells us that the UK must quit the European Union because it is “the will of the people”. Despite aligning himself in the Remain campaign during the referendum, opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn says that we must pursue Brexit because it is “the will of the people”. Many Labour MPs, who are critical of Corbyn and believe that leaving the EU will be a disaster, voted to start the exit process, without any guarantees or conditions, because it is “the will of the people”.

This is now the dreadful state of our democracy. On crucial matters such as immigration and Brexit, we are governed by tabloid headlines, opinion polls and lie-infested referendums. The “will of the people” has become the catch-phrase of the cowering, lazy or unprincipled politician. No longer driven by truth or principle, many of them knowingly connive in disaster because it is regarded as the peoples’ will.

Where can following “the will of the people” lead?

Polls show that the use of torture has sometimes, even recently, received majority support from the US public. President Donald Trump was elected after expressing a desire to re-introduce torture. Torture is “the will of the American people” – as some might put it.

But the use of torture has been against the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution since 1791. The very role of a constitution is to help protect rights and freedoms, even if “the will of the people”, or of a deviant President or Prime Minister, would take them away. One of the limits to democracy is that it should not be able to overturn our human rights.

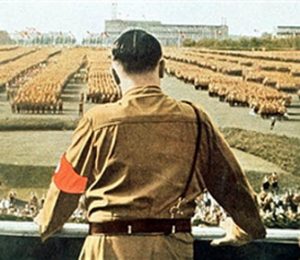

Dictators and populists are fond of referendums because they deploy “the will of the people” against constitutional safeguards. Hitler held a referendum in 1933, to garner mass support to withdraw from the League of Nations. In 1934 he held another referendum, which endorsed his bid for supreme power in Germany. Yet another referendum in 1936 ratified Hitler’s military occupation of the Rhineland and his one-party state. A fourth referendum in 1938 approved Hitler’s annexation of Austria. All propositions in these plebiscites received huge majorities.

Dictators and populists are fond of referendums because they deploy “the will of the people” against constitutional safeguards. Hitler held a referendum in 1933, to garner mass support to withdraw from the League of Nations. In 1934 he held another referendum, which endorsed his bid for supreme power in Germany. Yet another referendum in 1936 ratified Hitler’s military occupation of the Rhineland and his one-party state. A fourth referendum in 1938 approved Hitler’s annexation of Austria. All propositions in these plebiscites received huge majorities.

The death penalty

In recent polls in the USA, 60 per cent of the adult population supported the death penalty for murder, despite 64 per cent also believing that it does not lower the murder rate and 59 per cent believing that innocent people had been wrongly executed in the previous five years.

In the UK in 1983, around 75 per cent of people were in favour of the death penalty. Although recent polls show a lower level of support, it is still close to 50 per cent.

In the UK in 1983, around 75 per cent of people were in favour of the death penalty. Although recent polls show a lower level of support, it is still close to 50 per cent.

Imagine that we had a referendum to re-introduce the death penalty in the UK. Thanks to some reactionary newspapers, it is possible that the proposal would gain majority support. But that does not justify its re-introduction, even if it was “the will of the people”. The morality of a law cannot be decided by popular vote.

Should homosexual acts be legal?

In some states of the USA there were laws prohibiting sodomy (between same-sex or different-sex couples) until 2003. As recently as 2004, the number of people polled in the USA who thought that homosexual acts should be illegal exceeded the number who thought they should be legal.

By these measures, according to “the will of the people” homosexual acts should not have been made legal in 2003 or 2004.

By these measures, according to “the will of the people” homosexual acts should not have been made legal in 2003 or 2004.

But opinions change. This is another major problem with being governed by “the will of the people”.

After 2004, support in the USA for the legality of homosexual acts rose steadily. By 2016, the number supporting legality exceeded the contrary view by 40 per cent.

in the UK, as recently as 1998, 50 per cent of respondents in a poll thought that homosexual acts were “always” or “mostly” wrong, compared with 31 per cent saying they were “rarely” or never wrong.

Since then, opinion has switched, largely because leading politicians in the Tory as well as other major parties (with the notable exception of UKIP) have countered a sizeable segment of public opinion and underlined gay rights as a matter of principle.

By 2012, only 28 per cent of respondents in the UK thought that homosexual acts were “always” or “mostly” wrong, compared with 57 per cent saying they were “rarely” or never wrong. The will of the people can change.

The “will of the people” can be wrong or immoral

Whatever the “will of the people”, homosexual acts are either morally admissible or immoral. Moral principles are not determined by referendums or opinion polls.

Instead, they must be the subject of ongoing, informed debate, guided by the need to minimise harm, alongside “an egalitarian conception of the good, focusing on equal opportunities for a worthwhile life” (as Philip Kitcher puts in his important book on The Ethical Project).

Instead, they must be the subject of ongoing, informed debate, guided by the need to minimise harm, alongside “an egalitarian conception of the good, focusing on equal opportunities for a worthwhile life” (as Philip Kitcher puts in his important book on The Ethical Project).

Consider another illustration. In 1984, 49 per cent of the UK public agreed “a man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”. But by 2012, only 13 per cent subscribed to this view.

Considerations of equal rights and equality of opportunity militate against such gendered attitudes and the discrimination that they sustain. While there is much more to be done, arguments have been won, opinions have changed and progress has been made. People can be persuaded that their previous opinions were wrong.

The need for experts

Just as votes cannot establish what is moral or immoral, they cannot determine what is scientifically valid and what is not. A majority of Americans would disregard claims concerning human-induced climate change. For many Americans, they are all part of a “hoax” to promote more intervention by the Federal Government.

Democratic votes cannot establish the veracity of scientific claims. Science proceeds through detailed scrutiny of claims by experts in a specialist field and a dialogue of different expert views. It thus creates an evolving consensus over what truths have been established and what research must be prioritised for further investigation.

In the case of climate change, there is a strong consensus that human activity is leading to global warming. Albeit imperfect, this is the best indication we have of scientific truth. It is not the opinion of the general public, most of whom do not understand climate science.

In the case of climate change, there is a strong consensus that human activity is leading to global warming. Albeit imperfect, this is the best indication we have of scientific truth. It is not the opinion of the general public, most of whom do not understand climate science.

Another common fallacy, perpetrated by people who do not understand economics, is that we should treat the budgeting problems of a national economy in the same way that we treat our individual or household budgets. This is the “every housewife knows” economics of Margaret Thatcher and her ilk.

This mistaken view ignores the capacity of many sovereign states to issue money and sustain deficits: unlike individuals or firms, such states cannot go bankrupt. It ignores the fact that what may be true for an individual may not be true in the aggregate, as Keynesians and others have pointed out for decades.

Many economists (possibly most economists in the UK) accept this Keynesian argument. But it is difficult to get the point across to the general public, so that they elect governments that pursue austerity policies, which reduce aggregate demand and economic growth, leading to increased debt.

The role of democracy

If the behaviour of most British MPs over Brexit were taken as a guide, there would be no role for MPs at all. They blindly follow “the will of the people”, even when they know that it will lead to adverse economic and political outcomes.

If this were a valid guiding rule, then MPs would be redundant. They could be replaced by online opinion polls on every question. The public would be invited to vote over every piece of legislation and “the will of the people” could be upheld.

If this were a valid guiding rule, then MPs would be redundant. They could be replaced by online opinion polls on every question. The public would be invited to vote over every piece of legislation and “the will of the people” could be upheld.

Before long we might be putting immigrants in sealed trains to remote or foreign destinations, and publicly flogging delinquents to teach them a lesson.

Democracy is vital not because it provides a means of implementing “the will of the people” on any specific proposal. The primary purpose of democracy is to legitimate government. It replaces unacceptable claims that rulers are legitimised by the “will of God” or by their family lineage.

There is a strong case for improving our democratic institutions, and the functioning of democracy itself. There are also forceful arguments for increasing participation in some local and workplace decisions, where we are intimately affected and have local knowledge. But there are severe practical and moral limits to the extension of democracy over all our affairs.

At least at the national level, in any large and complex socio-economic system, democracy must involve representatives rather than delegates. Representatives must be given some autonomy to seek expert advice and make judgments on complex issues. Extensive participatory democracy in such circumstances is both unfeasible and undesirable.

Members of Parliament receive a mandate from their electorates to represent their interests. Representing interests does not mean polling opinions: that is the lazy and irresponsible option. Instead it is a matter of exercising informed judgment. It is a question of deliberation and interpretation, involving the use of expert advice. We know that MPs often get things wrong. That is why their constituents have the opportunity to remove them at the next election.

The reactionary media are not solely to blame

The reactionary media and their malign influence on public opinion are not the sole cause of the current political malaise in Britain and the USA. Among others, one can blame the intellectually-lazy part of the Left, which trots out the mantra of “democratic control” whenever it sees a policy problem.

One can also blame the majority of economists, who have abandoned all moral considerations save for utility maximisation (or mere “satisfaction”) by “rational fools” (the term used by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen).

Hence it is not just the reactionary media that are to blame. Many political activists have been intellectually lazy for too long. We need an enhanced and better-informed conversation concerning rights, morality and practical institutional design.

Armed with this knowledge, we need to hold our representatives to account, and expose the laziness and lack of principle of those who blindly follow “the will of the people”. If they see themselves as nothing more than unintelligent voting machines, then they should give up their positions to others, who would be guided by moral principles and offer greater dedication to the true interests of the people that they are supposed to serve.

21 February 2017

Minor edits – 28 February, 7 March, 4 May

|

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

Bibliography

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Kitcher, Philip (1993) The Advancement of Science: Science without Legend, Objectivity without Illusions (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press).

Kitcher, Philip (2011) The Ethical Project (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Sen, Amartya K. (1977) ‘Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory’, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6(4), pp. 317-44.

Posted in Brexit, Democracy, Left politics, Liberalism, Nationalization, Property, Uncategorized

January 28th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The political earthquakes of 2016 are probably the beginning of a series of major ruptures in world politics. Donald Trump was elected in the USA, Britons voted for Brexit, Turkey lurched toward dictatorship, Brazil ejected a democratically-elected president, Russia extended its global influence, and China tightened internal security while building military bases in the South China Sea.

From America to Asia, authoritarian nationalism is on the march. The future of old alliances is cast in doubt, raising a renewed spectre of global war.

These seismic changes should prompt us to reconsider our priorities. Is ‘neoliberalism’ – whatever that means – our main enemy? Or is it rising authoritarianism and nationalism instead?

We have been here before, albeit with much less dangerous military weapons. The rival imperialisms of the nineteenth century led to the First World War. Collapsing imperial dynasties triggered revolution in Central and Eastern Europe. Communists successfully seized power in Russia in 1917. Post-war political and economic turbulence led to the triumph of fascism in Italy, Germany and Spain. Imperial Japan invaded nationalist China.

I am not suggesting that history will repeat itself in the same way. But it is important to understand how the tectonic plates of political change affected the way we understand and map political positions, and the way in which we prioritise political issues.

The thirty-year squeeze (1918-1948)

Europe suffered economic depression for much of the interwar period. The financial crash of 1929 exacerbated the crisis and led to a collapse of world trade. Liberal defenders of the market economy were put on the defensive: capitalism seemed at the end of its tether.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Meanwhile, some intellectuals from the USA and Britain – including Labour stalwarts George Bernard Shaw and Sidney and Beatrice Webb – visited the Soviet Union brought back glowing accounts of an expanding economy and a joyful population. (The Soviet propagandists explained away disasters such as the Ukranian Famine as resulting from sabotage by rich peasants or foreign agents.)

With the crisis of capitalism, the rise of fascism and the apparent success of Soviet Russia, many British and American radicals became Communists or fellow travellers. For them, liberalism and the defence of the market economy seemed a weak or unviable option.

The choice seemed to be between two forms of authoritarian government: much better the one that proclaimed equality and opposed racism. (But in reality, the Stalin regime promoted antisemitism, genocide against several other ethnic minorities, and dramatic internal inequalities of power.)

Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill in 1941

The alliance between Russia and the West in the Second World War smothered criticism of what was really going on within Stalin’s regime. But, with the beginning of the Cold War in 1948, socialists were forced to make a choice between either supporting an antagonistic and undemocratic foreign power, or aligning with the USA and its allied democracies.

Labour under Clement Attlee aligned with the West. But rose-tinted visions of Soviet Russia or (from 1949) Mao’s China lived on among he Left.

In major European democracies, the thirty years between the end of the First World War and the start of the Cold War had seen liberalism squeezed, between socialism on the one hand, and reactionary authoritarianism on the other.

‘American imperialism’ and the rise of neoliberalism

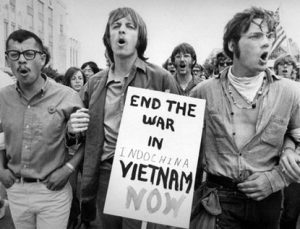

Things were different in the USA, which polarised between forms of Republican conservatism and Democratic liberalism. But rising tensions in the Cold War, and the eruption of the Vietnam War in the 1960s, made American-style liberalism less attractive for the global Left.

Marxist-led national liberation movements in Cuba, Indochina and elsewhere kept the collectivist vision alive for the Left around the world. Liberalism was see as the fake ideology of American imperialism and the global bourgeoisie.

Marxist-led national liberation movements in Cuba, Indochina and elsewhere kept the collectivist vision alive for the Left around the world. Liberalism was see as the fake ideology of American imperialism and the global bourgeoisie.

Some have argued that neoliberalism was reborn in the 1970s, when conservatives such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher adopted a vision of expanding markets and a contracting state. Although the Left could never agree on what ‘neoliberalism’ meant, they mostly agreed that it was the main enemy.

Much of the Left, throughout the world, had never got rid of its agoraphobia – its fear of markets. Private enterprise and market forces were always and everywhere seen as the problem. Liberals, who defended private property and markets as well as human rights, were mocked as the bourgeois enemy.

Our brave new world

But the global tectonic plates are now shifting abruptly, in an erupting national and international crisis, as big as anything since 1948.

Nationalist leaders strut around the world stage. They stock up their nuclear and conventional arsenals and jostle for geopolitical advantage.

Torture is endorsed. Journalists are threatened or imprisoned. Scientific findings on climate change are denied. Intellectuals and experts are ridiculed. Ignorance and dogma are celebrated. Truth is swamped by lies. Legislation protecting workers and the poor is undone. Minorities are attacked and made scapegoats. Racism is given licence. People suffer discrimination on the basis of their religious or other beliefs. Democratic systems are damaged. Judges and lawyers are treated as traitors. The rule of law is undermined.

In this dangerous new world, it matters less whether that railway is nationalised or whether water distribution is in public ownership. Forms of ownership are always secondary to the actual provision and distribution of vital goods and services. But when our rights and liberties can no longer be taken for granted, questions over forms of ownership move even further down the ranking of priorities.

The ubiquitous, trivialising idea that the Left is defined in terms of public provision, and Right as private provision, is historically recent and a gross reversal of their original meanings. It is also a polarisation of lesser relevance in this world of rising authoritarian nationalism.

Our fundamental rights, our liberty, and the rule of law are now increasingly threatened. Their defence becomes the great struggle of our time.

This lesson is hardest for Americans and Britons, who were spared domestically from the jackboots of twentieth-century despotism. Struggles for British and American national liberty are beyond living memory. We have grown fat and lazy on the fruits of the liberal order. We have taken for granted its institutions and underestimated their fragility. We must repair our vigilance.

The liberal opportunity

For 100 years, for the reasons given above, liberalism has been marginalised. Now is its opportunity – indeed its urgent necessity.

Unlike our grandparents in the crisis-ridden 1930s, we have seen the socialist experiments of the twentieth century and counted their cost at 90 million lives. History and social science have more to teach us. If we wish to learn, we can know more about how markets work. We can understand the informational, organisational and other impediments to comprehensive national planning. We can appreciate why countervailing politico-economic power, based on a strong private sector, are necessary to buttress democracy and resist authoritarianism. The twentieth century has taught us these lessons.

The old Marxist mantra of bourgeoisie versus proletariat is also ungrounded in reality. Instead we have a highly fragmented working class, much of it enduringly aligned with authoritarianism and nationalism. Marxism relies on a quasi-religious and nonsensical belief that the working class – whatever it actually believes or strives for – carries our human destiny.

Class struggle has mattered, but it has never been the main motor of history. What have mattered more have been struggles for power, by individuals, dynasties, nations, religions or ideological movements.

The Storming of the Bastille in 1789

Liberalism was one of those movements. Based on the imperatives of equality and liberty, it matured in the Enlightenment.

Liberalism rose up in the English Civil War of the 1640s, in the American Revolution of the 1770s, and in the French Revolution of 1789, in titanic struggles against despotism and oppression.

Now, once again, liberalism is centre stage, as the enemy of authoritarian nationalism.

The liberal rainbow

Its allies are not those who pander to authoritarianism by eroding civil liberties, or do the spadework of the nationalist Right by making immigration (rather than assimilation) a foremost problem. The prime allies of liberalism are all those who defend liberty and human rights. But therein lies a concern, which must be discussed.

From the beginning, liberalism has harboured different views on the role of the state and of the degree of state intervention required in the economy and society. On the one hand there are liberals – sometimes called libertarians – who wish to minimise the role of the state.

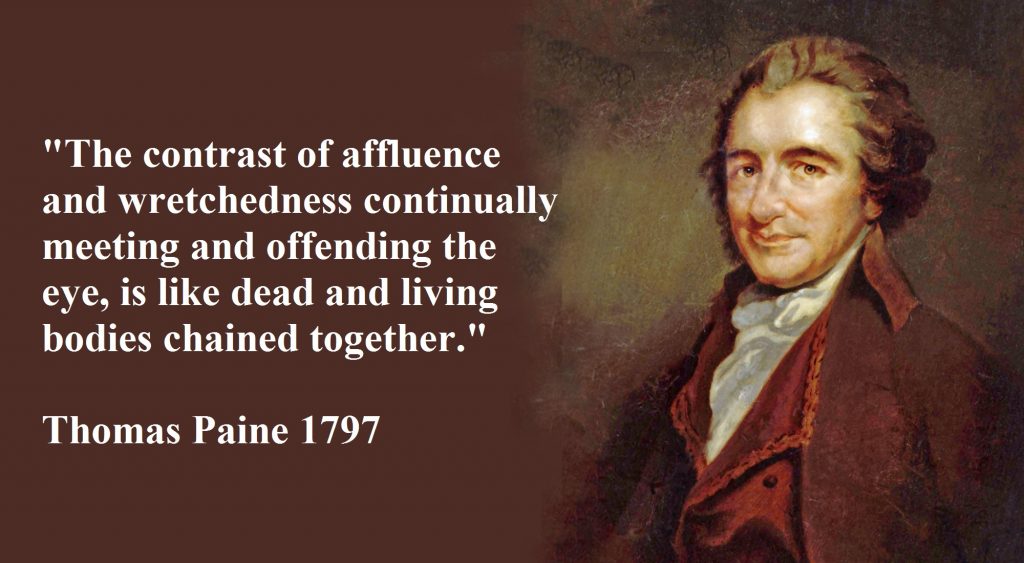

Thomas Paine

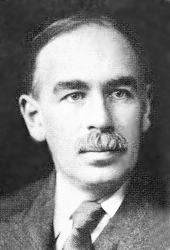

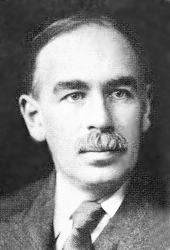

John Maynard Keynes – another great liberal – argued that state regulation of financial markets and counter-cyclical expenditures are necessary to stabilise the capitalist system. Keynes showed that economic austerity is a flawed doctrine. Government deficits are best reduced by growth: budget cuts can contract the entire economy and make the problem worse.

There is a spectrum of views between individualist and social-democratic liberalism, but all liberals are united in their defence of individual liberty, human rights and political democracy. The diverse colouring of this rainbow does not diminish its united opposition to the dark intolerance and division that is exacerbated by authoritarian nationalism.

The struggle for liberty and equality has always been vital. But many twentieth-century radicals were diverted by the delusions of socialism. The renewed rise of authoritarianism has shown us again that liberalism is the vital political movement of the modern age.

28 January 2017

Minor edits: 29 January, 1, 16 May 2017

|

This book by G. M. Hodgson elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

Bibliography

Allett, John (1981) New Liberalism: The Political Economy of J. A. Hobson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Beveridge, William (1944) Full Employment in a Free Society (London: Constable).

Clarke, Peter (1978) Liberals and Social Democrats (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Claeys, Gregory (1989) Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (London and New York: Routledge).

Courtois, Stéphane, Werth, Nicolas, Panné, Jean-Louis, Packowski, Andrzej, Bartošek, and Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999) The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Keane, John (1995) Tom Paine: A Political Life (London: Bloomsbury).

Keynes, John Maynard (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Macmillan).

McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen (2017) ‘Nationalism and Socialism Are Very Bad Ideas: But liberalism is a good one’, Reason.Com, February. http://reason.com/archives/2017/01/26/three-big-ideas

Monbiot, George (2016) ‘Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems’, The Guardian, 15 April. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot.

Townshend, Jules (1990) J. A. Hobson (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Venugopal, Rajesh (2015) ‘Neoliberalism as a Concept’, Economy and Society, 44(2), pp. 165-87. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013356.

Posted in Brexit, Common ownership, Democracy, Donald Trump, Immigration, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Populism, Private enterprise, Right politics, Socialism

November 18th, 2016 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

“One of the most important essays you will read in 2016” @Rokewood

What caused the election of Donald Trump? I am deeply dissatisfied by some of the quick answers to this question.

The leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition had an instant answer. Jeremy Corbyn blamed the left’s association “with the forces of globalisation during the Obama administration”. Instead, he insisted, we need to reject “that free market, economic thinking, which processed deindustrialisation in Britain”.

Naomi Klein

Others used different words on the same “free market” theme. Naomi Klein put it bluntly: “the force most responsible” for Trump’s success was “neoliberalism”. This worldview, “fully embodied by Hillary Clinton and her machine”, was “no match for Trump-style extremism.”

Trump won over US voters because: “Under neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatisation, austerity and corporate trade, their living standards have declined precipitously.”

The Guardian columnist George Monbiot followed with a historical piece, claiming that “the events that led to Donald Trump’s election started in England in 1975”, when Margaret Thatcher embraced the free-market “neoliberal” philosophy of Friedrich Hayek. This was a harbinger of the global rise of free-market thinking that allegedly wrought havoc in recent years.

Both Klein and Monbiot argue that Trump capitalised on the failure of other politicians to deal with the adverse effects of neoliberalism.

There is no doubt that the global expansion of capitalism in recent decades has been hugely disruptive, shifting millions of manufacturing jobs to East Asia. In the absence of adequate retraining and investment, it has led to declining opportunities for large swathes of the working population in North America and Europe.

Trump tapped into working class discontent. In important respects his policies are not neoliberal, by any reasonable definition of that term. In his campaign, Trump used anti-neoliberal, protectionist slogans such as high import tariffs and closed borders.

George Monbiot

But why did it take so long for people to react to “neoliberalism” and vote in this way? As Monbiot argued, the current so-called “neoliberalism” got under way in the 1970s. It accelerated after the beginning of economic reform in China in 1978 and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in1989. The whole world was then opened up for trade.

But while right-populist movements had emerged, they were then far from power. Tony Blair won a landslide election in 1997 and increased public spending on welfare, education and health. Three years after Blair had won a third election, the United States elected its first black President.

If neoliberalism and stagnant living standards had been around since the 1970s, then why did it take 40 years for a Trump-like demagogue to be elected? The political wind swung decisively to the right more recently, after the Great Crash of 2008.

But it is also difficult to explain Trump’s populist success as a targeted reaction to the financial crash. The removal of some banking regulations, by Bill Clinton in the US and Gordon Brown in the UK, did exacerbate the lending boom that led to the crash of 2008.

Yet, despite his protectionism, Trump offers still more deregulation. He is not targeting the bankers as part of the “elite”. On the contrary, he has pledged to repeal the Dodd-Frank Act, which was designed to curb some of the excesses of the financial sector. As Larry Elliott put it: “This looks curious for someone trying to surf a tidal wave of populist anger against the bankers.”

Putting the blame on “neoliberalism” underestimates the way in which outsiders such as Trump and Farage have created populist movements that blame “the elite” and offer simplistic solutions, such as to “curb immigration”. Blaming “neoliberalism” underestimates the pernicious influences of racism and anti-Muslim prejudice. Simplistic economic explanations of Trump’s victory ignore much stronger evidence of other factors at work.

Putting the blame on “neoliberalism” underestimates the way in which outsiders such as Trump and Farage have created populist movements that blame “the elite” and offer simplistic solutions, such as to “curb immigration”. Blaming “neoliberalism” underestimates the pernicious influences of racism and anti-Muslim prejudice. Simplistic economic explanations of Trump’s victory ignore much stronger evidence of other factors at work.

The Pavlovian leftist response of blaming markets or “neoliberalism” for “all our problems” is far off the mark.

What is neoliberalism?

Monbiot is keen to identify “neoliberals” such as Hayek as the villains. According to Monbiot:

“Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. … Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone.”

I shall pass over the many flaws in the essay from which the above passage is quoted. Monbiot conflates the different views of Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, and he is inaccurate on several details. Note also that Monbiot does not highlight deregulation of the financial sector in this passage.

After taking on board Monbiot’s definition of neoliberalism, let us consider the extent to which it has been achieved in the real world.

Has neoliberalism been achieved in practice?

Monbiot described how in the 1970s “elements of neoliberalism, especially its prescriptions for monetary policy, were adopted by Jimmy Carter’s administration in the US and Jim Callaghan’s government in Britain.” He is unclear on the details, but presumably in part he refers to Callaghan’s embrace of monetarist ideas from 1976 to 1979.

Milton Friedman

Monetarism, incidentally, is not obviously the same as neoliberalism. While monetarists such as Friedman were free-marketeers, monetarism’s central claim is that the main cause of inflation is the rise in the money supply – a thesis that (as Friedman himself recognised) could also apply to a planned economy. Indeed, this central monetarist tenet was adopted by some Marxist economists.

“After Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan took power, the rest of the [neoliberal] package soon followed: massive tax cuts for the rich, the crushing of trade unions, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services.”

He is right. Albeit to different degrees in different countries, these things happened.

But go back to Monbiot’s checklist definition of neoliberalism, as quoted above. He saw neoliberalism as minimising “tax” not simply “tax cuts for the rich”. Has this happened?

Ronald Reagan & Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher reduced taxation for the rich. But the overall tax burden (all taxes as a percentage of GDP) rose during her period of office. This figure fell in the 1990s and has fluctuated from 1997 in a range between 35 per cent and 38 per cent of GDP. The UK austerity governments since 2010 have not reduced the overall tax take significantly.

Similarly, Ronald Reagan began by cutting income taxes for the rich, but ended his eight-year term of office with a Federal percentage tax take almost identical to that of his predecessor Jimmy Carter, and slightly above the average for the entire 1970-2009 period.

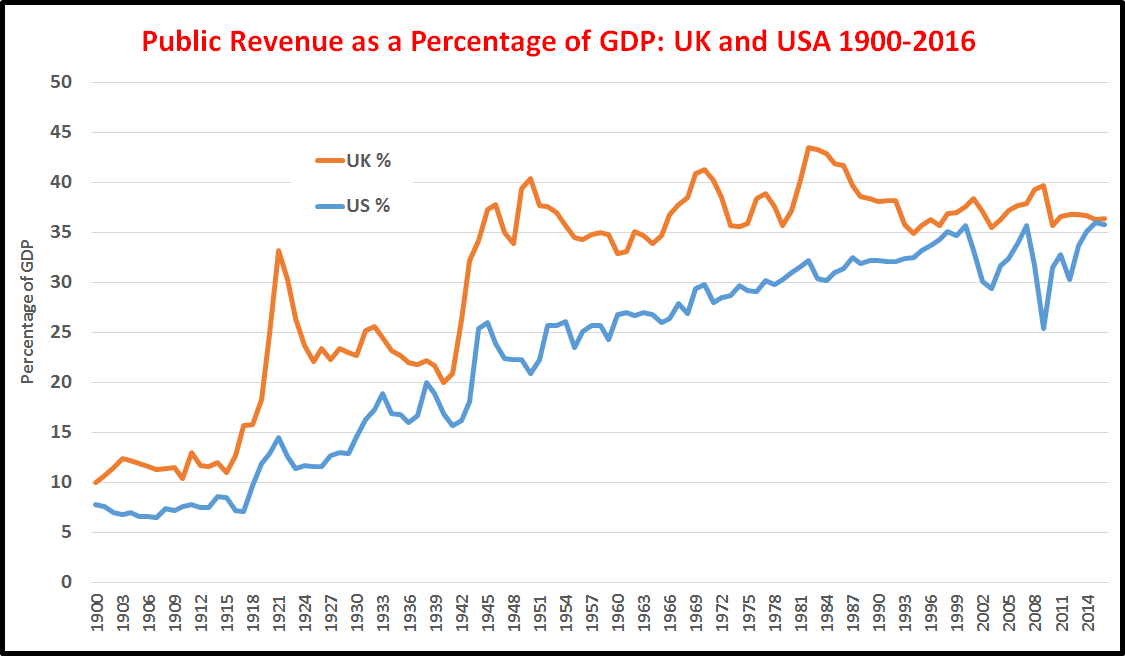

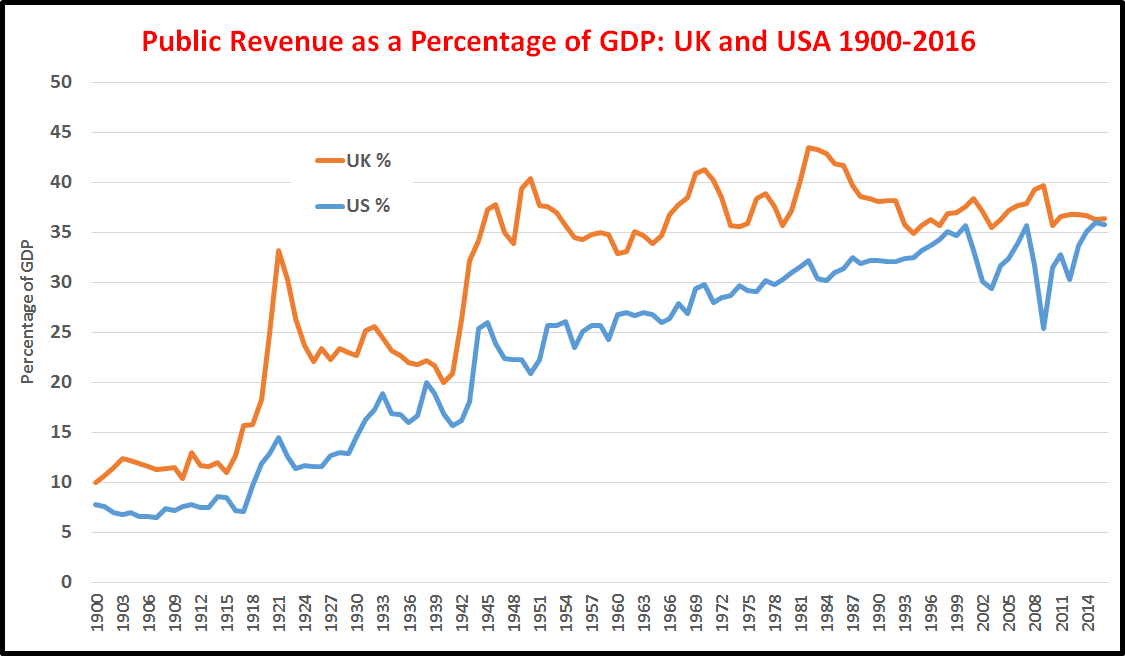

The “neoliberal” mission of massive overall tax cuts was not achieved under Thatcher or Reagan, or under subsequent administrations. Put in a longer historical perspective, taxation and public spending in the UK and USA today are much higher than they were before the Second World War.

The above figure shows the tax revenues, from national, state and local government combined, for the UK and the USA from 1900 to 2016. The alleged era of “neoliberalism” from the 1970s has not been associated with declining tax revenues. If anything, the “neoliberal” era of a minimal state was pre 1914, not post-1975.

What is characteristic of fiscal policy in the UK and USA is not the alleged “neoliberal” overall reduction of taxation but a lightening of taxation on the rich, and a failure to redistribute sufficiently, in the face of widening inequality.

Klein is probably right to suggest: “A good chunk of Trump’s support could be peeled away if there were a genuine redistributive agenda on the table.” But she, with Corbyn and Monbiot, are wrong to chime in with the crude anti-market mantras that have disabled the Left for 180 years. In building a redistributive agenda we must look to Thomas Paine, rather than Robert Owen or Karl Marx.

Privatisation: against dogma

By contrast, Monbiot’s other point, about growing privatisation since the 1970s, has been borne out by the evidence. In the UK, USA and much of the world there has been massive privatisation and outsourcing of public services.

Unlike any false claim that “neoliberalism” has reduced overall taxes, the increase of privatisation is manifest. In addition, it has sometimes led to deleterious consequences including lower pay for workers and a reduced quality of services.

Unlike any false claim that “neoliberalism” has reduced overall taxes, the increase of privatisation is manifest. In addition, it has sometimes led to deleterious consequences including lower pay for workers and a reduced quality of services.

But Corbyn and Monbiot speak and write as if privatisation is necessarily bad – always and everywhere it is seen as a negative policy. This doctrinaire stance simply inverts the claim of the crudest free marketeers, who claim that state provision is always bad and that private provision is always good. The Corbyn-Monbiot stance simply turns this upside-down. It is equally dogmatic. It is based on ideology, not evidence.

Regarding markets as always bad, amounts to agoraphobia or fear of markets (from the Greek words agora for market, and phobia for fear). This is an inversion of the kratophobia of the free-marketeers – a fear of government or of the state.

Instead of these ideologically-driven, simplistic positions, it is necessary to be more pragmatic. Some privatisations work. Others do not. Some state provision is effective. Some is wasteful and inefficient. We need to look at individual cases to understand why.

There are many case studies to look at and they are too wide-ranging to be reviewed here. A good start would be to look at an important early article on privatisation by John Goodman and Gary Loveman in the Harvard Business Review. They wrote:

“the issue is not simply whether ownership is private or public. Rather, the key question is under what conditions will managers be more likely to act in the public’s interest … managerial accountability to the public’s interest is what counts most, not the form of ownership.”

Goodman and Loveman argued that profits and the public interest overlap best when the privatised organisation is in a competitive market. Competition from other companies can discipline managerial behaviour. Consequently, there is little point in privatisation if competition is lacking.

Subsequent research has shown that other factors are involved as well. Instead of being driven by dogma, we need to be pragmatic and experimental, taking account of research.

Jeremy Corbyn

You may respond that Corbyn is pragmatic, because he has declared that he is in favour of a mixed economy: he accepts a private as well as a public sector. But notice the imbalance in his presentations. He treats public provision as ideal, and the private sector as an expedient to be tolerated, at least for a while.

Corbyn says he accepts a mixed economy, but he has offered has no defence of private sector. His “mixed economy” could be a stopping point on the road to a fully-socialist planned economy, where private enterprise is pushed to the side-lines.

Declining public provision?

Ken Loach’s moving film, I, Daniel Blake, portrays the heart-breaking human consequences of the UK Conservative government’s shredding of the welfare safety net for the poor. Attempts to reduce public spending in many countries have led to millions of human tragedies like this.

Ken Loach’s moving film, I, Daniel Blake, portrays the heart-breaking human consequences of the UK Conservative government’s shredding of the welfare safety net for the poor. Attempts to reduce public spending in many countries have led to millions of human tragedies like this.

Doctrinaire austerity policies – which fail in their own terms because they depress economic demand for goods and services and create more unemployment – have been adopted by many governments and imposed by the European Union.

All this is real, and tragic. Millions have suffered because of such misguided policies. But we should not jump to the conclusion that “neoliberalism” has been successful in moving toward a minimal economic role for the state.

All this is real, and tragic. Millions have suffered because of such misguided policies. But we should not jump to the conclusion that “neoliberalism” has been successful in moving toward a minimal economic role for the state.

In my book Conceptualizing Capitalism I examined differences and changes in public social spending in different developed countries from 1980 to 2005, using OECD data. The principal components of public social spending include health services, old age benefits, unemployment benefits, incapacity-related benefits, family support, active labour market public programs, and housing benefits.

Amounts of public spending as percentages of GDP (in 1980 and 2005) are shown below.

|

1980 |

2005 |

change |

| Australia |

10.3 |

16.5 |

+6.2 |

| Austria |

22.4 |

27.1 |

+4.7 |

| Belgium |

23.5 |

26.5 |

+3.0 |

| Canada |

13.7 |

16.9 |

+3.2 |

| Denmark |

24.8 |

27.7 |

+2.9 |

| Finland |

18.1 |

26.2 |

+8.1 |

| France |

20.8 |

30.1 |

+9.3 |

| Germany |

22.1 |

27.3 |

+5.2 |

| Italy |

18.0 |

24.9 |

+6.9 |

| Japan |

10.2 |

18.5 |

+8.3 |

| Netherlands |

24.8 |

20.7 |

–4.1 |

| Norway |

16.9 |

21.6 |

+4.7 |

| Portugal |

9.9 |

23.0 |

+13.1 |

| Spain |

15.5 |

21.1 |

+5.6 |

| Sweden |

27.1 |

29.1 |

+2.0 |

| Switzerland |

13.8 |

20.2 |

+6.4 |

| UK |

16.5 |

20.5 |

+4.0 |

| US |

13.2 |

16.0 |

+2.8 |

Public Social Spending as Percentage of GDP in Selected Countries

Most countries increased their public social spending, during a period when the ideology of privatization was resurgent. The Netherlands is an exception. Note that the increases in public social spending are not explained by rises in unemployment benefit, because generally this comprises a small proportion of public social spending.

Of course, it needs to be emphasised that there is an ideologically-driven agenda that has led to deep cuts in some welfare and has been gravely damaging for the poor. But we are far from re-entering the era of the minimal state.

Pursuing unicorns

Much of the hysteria against “neoliberalism” draws from the Left’s deep rooted antipathy to markets. Let’s briefly address this.

First, they may be alternatives to markets in modern, large-scale economic systems but they would greatly out-do the miseries inflicted on the fictional Daniel Blake and his millions of real-world counterparts.

Karl Marx

Every attempt to get rid of markets, since Robert Owen and Karl Marx proclaimed their redundancy in the nineteenth century, has led to famine, repression and the termination of democracy. Look to Stalin’s Russia, Mao’s China, Cambodia, Cuba and Venezuela. Twentieth-century Communism resulted in over 90 million deaths.

In the light of twentieth-century experience it would be worse than foolhardy to make yet another attempt to minimise markets, or as Klein oddly put it, “corporate trade”.

A better way is possible, but it involves taming and supplementing markets, not repressing them. It means regulating corporations, not casting them as sorcerers of evil. But sadly, agoraphobia still afflicts many on the left.

“It seems to me that the questions we urgently need to ask ourselves are these: is totalitarianism the only means of eliminating capitalism? If so, and if … we abhor totalitarianism, can we continue to call ourselves anti-capitalists? If there is no humane and democratic answer to the question of what a world without capitalism would look like, then should we not abandon the pursuit of unicorns, and concentrate on capturing and taming the beast whose den we already inhabit?”

Excellent. But since then he has gone down the rocky road of blaming “neoliberalism” for “all our problems”. Without defending some role for private property or markets, he thereby allies himself with the many leftists who now describe anyone defending private property or markets as “neoliberal”.

Has Monbiot now abandoned the idea of taming the capitalist beast? Does he wish to kill it instead?

In April 2016 he wrote: “Every invocation of Lord Keynes is an admission of failure.” So he junked the best macroeconomic theory we have for limiting some of the excesses of capitalism. His grounds for doing so were these:

“Keynesianism works by stimulating consumer demand to promote economic growth. Consumer demand and economic growth are the motors of environmental destruction.”

John Maynard Keynes

Wrong. “Consumer demand and economic growth” can destroy the planet, but only if that demand and growth relate to non-renewable material resources. Much demand and growth in modern economies is for services. Intangible assets now make up much of corporate wealth. For example, there are demands for information and education, and such services are added to GDP. There is no necessary reason why economic growth in a modern information-rich economy should ruin the planet. Keynes is still relevant.

Those that have pursued unicorns have imagined that it is possible to design a better system than capitalism. Monbiot says the same, declaring that for the Left

“the central task should be to develop an economic Apollo programme, a conscious attempt to design a new system, tailored to the demands of the 21st century.”

This puts him in full, unicorn-chasing mode. One of the biggest mistakes by early socialists was to ignore the massive complexity of modern economic systems and attempt to “design a new system” at the behest of some utopian dreamer.

Instead, what is required is careful, incremental, experimental change, retaining the flexibility and devolved autonomy afforded by widespread private property. This autonomy allows for multiple experiments and deeper learning from mistakes.

While state intervention is necessary, no complete or adequate overall “design” is possible, because of the way much knowledge is irretrievably dispersed throughout the economy. The economies of the twenty-first century are more knowledge-intensive than those before. Hence the possibilities of comprehensive central planning or “design” are even more limited.

Neoliberalism and economic man

“as modern psychology and neuroscience make abundantly clear – human beings, by comparison with any other animals, are both remarkably social and remarkably unselfish. The atomisation and self-interested behaviour neoliberalism promotes run counter to much of what comprises human nature.”

The first sentence is valid and important. The second is simplistic. As I elaborate in my book From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities, strong evidence from psychology, evolutionary biology and primatology shows that the picture of self-seeking “economic man”, which dominated mainstream economics until recently, is deeply flawed.

The first sentence is valid and important. The second is simplistic. As I elaborate in my book From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities, strong evidence from psychology, evolutionary biology and primatology shows that the picture of self-seeking “economic man”, which dominated mainstream economics until recently, is deeply flawed.

But that does not mean that we can or should get rid of markets. Our capacities for cooperation evolved culturally and genetically because our ancestors hunted and foraged in groups, rarely numbering more than 200 individuals, for millions of years. Relying on emotions and facial expressions, we developed sophisticated social mechanisms to engender trust and cooperation, and to enforce social rules.

As larger-scale cities emerged about 14,000 years ago, these face-to-face mechanisms could no longer be relied upon exclusively to regulate social interactions. Institutions such as law, property and contract were developed to deal with these more impersonal, non-familial, transactions.

Every human civilisation that has developed has relied on property, trade and contracts. These require different enforcement mechanisms, but they too require measures of trust and moral obligation, as Adam Smith made clear in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. The idea that markets inevitably corrode away all social ties is mistaken.

Even the Soviet-style economies of the twentieth century relied on some private property and trade. They failed because state bureaucracy stifled autonomy and innovation. China grew rapidly when it expanded the private sector after 1978.

Of course, the spread of the market would be detrimental if it invaded all our social relations, attempting to put prices on love and friendship and reducing everything else to money transactions. But a system of private property provides a degree of autonomy that is required to maintain non-market interactions at home and at work. Successful corporations create islands of cooperation and teamwork within their organisational boundaries.

Impersonal relations occur in bureaucracies as well as in markets. Large-scale systems of national planning also make much interaction impersonal. People become atomised; they become numbers, to be processed by bureaucrats and computers.

Impersonal relations occur in bureaucracies as well as in markets. Large-scale systems of national planning also make much interaction impersonal. People become atomised; they become numbers, to be processed by bureaucrats and computers.

The experience of centrally-planned economies in Russia, China and Eastern Europe shows that systems of state planning can be cesspits of human alienation and corruption, governed impersonally by disillusioned bureaucrats and corrupt state officials. I recommend the film The Lives of Others for a glimpse into that dark world.

Abandoning neoliberalism

I have written at further length elsewhere on the limits to markets. I accept Hayek’s explanation that comprehensive overall planning is dysfunctional. But I do not accept that everything should or can become a monetary transaction in its place.

Indeed, the growing use of information in a capitalist economy puts limits on the role of information as property. Furthermore, the very freedom of waged employees means that there are constraints on entering into contracts for future work. There are limited futures markets for labour. For such reasons, capitalism can never be a 100 per cent market system.